A 70-foot table stretches almost the length of a gallery.

It comes scattered with more than 300 translucent trivets, beaded in Lite-Brite colors; 193 faux fruits and vegetables, bejeweled; 109 wooden canes of every kind, plus 40 badminton rackets, 21 glass fish, and 18 leather slippers sheathed in sequins and buttons.

It would be easy to imagine that “Mammoth,” the new installation that opens Feb. 13 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in Washington, was the scattershot product of some pack-rat outsider.

“You would think I’m a hoarder,” agrees Nick Cave, who created the work. “But I am by no means interested in that at all. My personal space is very minimal.”

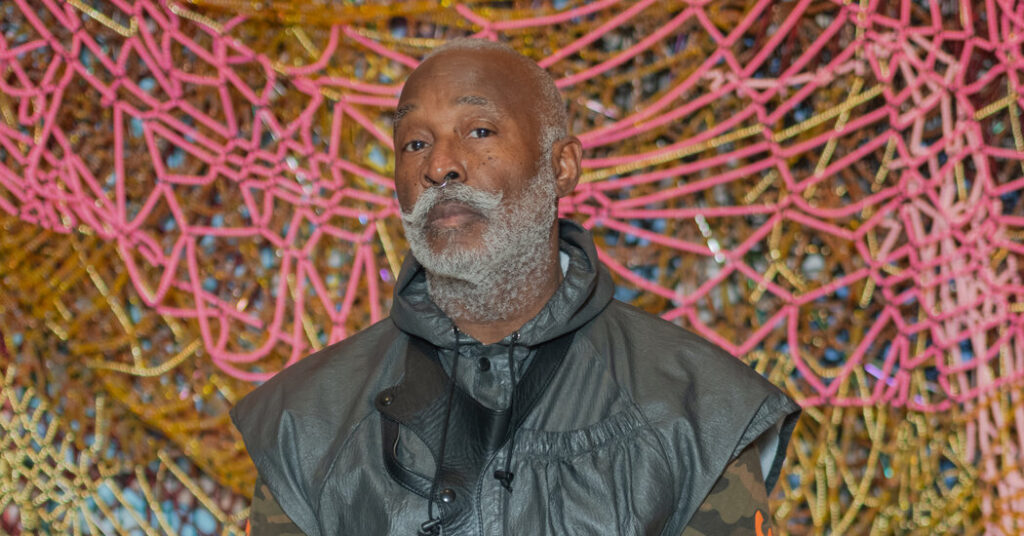

On the frigid Saturday in January that we meet in D. C. — the day before the East Coast shuts down for a snowstorm — Cave certainly doesn’t look like an anarchic outsider. About to turn 67, he keeps his gray hair and beard trimmed close; he’s dressed in tidy black sportswear, like a professor caught at home on a winter weekend. (Cave has taught for decades at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.) His red-and-white high-tops show a sophisticate’s grasp of pop culture: They’re by the Japanese brand Bathing Ape, marrying Tokyo street style to hip-hop cred. (Jay‑Z and Kanye West have been fans.)

In the art world, Cave is a distinct insider. His wearable sculptures called “Soundsuits” have been in group shows around the globe. He’s had surveys at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art and the Denver Art Museum.

Inspiration for Cave’s latest project arose from a “deep dive” into his history. “I come from a family of makers, musicians, poets, singers, craftsmen, woodworkers, quilters,” he says, “and that was something that I wanted to focus on.” Memories of summers spent on his grandparents’ farm, in Missouri, were especially important, as were the crafts that delighted his grandmother and her sisters and nieces — faux fruits and beaded trivets, among others.

For Sarah Newman, SAAM’s curator of contemporary art, Cave’s excavation of his past is vital to “Mammoth”: “It’s about memory, and creativity and the process of memory, and how memory affects our lives,” she said, as we took in Cave’s work.

But sometimes, old memories, however personal, can have wider and quite current implications. Couched in Cave’s dazzle in the new show is “a pervasive fear,” according to Newman, “without ever surfacing directly,” as she puts it in her catalog essay.

She writes about “Mammoth” as speaking to “the current ecological crisis as part of a broader reckoning with how we engage with the land and our shared history.”

She describes Cave’s “Soundsuits,” which launched his career a quarter century ago, as having equally political meaning: Born in response to the 1991 beating of Rodney King, they explored Cave’s “vulnerability as a Black man in America,” Newman writes — which is then echoed in the current show, she says.

In another essay, the art historian Cherise Smith bills “Mammoth” as the kind of “institutional critique” that shines a light on our museum-industrial complex. The jumbled objects in “Mammoth,” she says, “point to and thwart the ordering of museums’ collections, in turn indicating and circumventing the attendant classification to which museums subject people.”

The platform that holds Cave’s scatter of objects is in fact topped in white plastic that’s brightly lit from below, like the light table an anthropologist — a Smithsonian anthropologist — might use to study such artifacts.

And SAAM has the courage to entertain such critique, however cloaked in Cave’s bounty, at a time when its parent institution is more than ever under the Trump administration’s antiwoke microscope. For months, the Smithsonian has been grappling with White House demands to surrender records and wall texts from its museums, to be vetted for “improper ideology.”

How might the president feel about a Smithsonian exhibition by a Black gay artist “contending with issues of race, identity, and the changing climate,” as Newman has described “Mammoth,” when his administration has begun removing mention of climate change from our national parks? When talk of slavery has vanished from a Parks Service display on George Washington, our founding President and owner of enslaved people?

Cave himself imagined that his art might face pushback in Trump’s Washington. “I thought about it for a minute,” he told me, “but then I’m like, I’ve got to proceed forward. That will come — if it comes — and I will then address it.”

In an emailed statement responding to my questions, SAAM wrote that “there has been no outside influence on ‘Mammoth.’ The exhibition is being presented as it was conceived by the artist in concert with SAAM’s curatorial team.” (But it’s notable that the anodyne account of his project in the wall texts that I was later sent makes no mention of the issues of climate change, race or critique that are highlighted in the catalog.)

Speaking in person, Newman shies away from any combative take on Cave’s project. “I’m trying not to think about it in terms of the larger politics,” she says, “because I just don’t think that that is what Nick is thinking about.” But whether that’s true or not of what goes on in Cave’s mind (he tells me proudly of his presence at a No Kings march), his art certainly seems able to spark political thoughts in her, and in us.

As a critic, I admit to having been more worried, over the years, that the shiny objects in Cave’s art might be as likely to distract from tough thought as to provoke it. But “Mammoth” has a darkness that gives it heft.

The most striking thing about Cave’s table is the chaos of its objects — not organized to tell a story, maybe, about some golden farm moments, but disorganized to resist all orderly storytelling. Cave’s account of his project has some of the same discombobulation. Thoughts pile up inside sentences then go off in every direction, like cars at a traffic circle: “I don’t know anything, I don’t think — or do I? — I don’t know anything, and yet I know I know it,” he tells me.

Such talk evokes one of Samuel Beckett’s Cold War plays, or maybe the modernist prose that emerged from World War I, which could help explain Cave’s artwork as well: You might call it “stream of consciousness sculpture,” more committed to modern art’s classic breakdown of sense — often in response to crises even worse than our own — than to calling things cleanly to mind.

One of several tall sculptures that rise up from Cave’s table is a bicycle frame, married to an old telephone, married to a pair of glove molds, married to a TV antenna; it conjures the Dada accumulations of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, a Jazz Age artist who witnessed doughboys coming home mangled, or the self-destructing machines that Jean Tinguely cobbled together as the new atomic bombs threatened.

And then there’s the giant mural titled “Palimpsest (Promised Land)” that fills a vast wall beside Cave’s table. It was executed by the designer Bob Faust, Cave’s life-partner, and its imagery, Cave says, derives from that childhood farm in Missouri, “particularly the acres of land that I was able to have access to as a young kid.”

Except that hardly a bit of that will be visible in Cave’s show. On the day Cave and I met, Faust, a slim white man in a laborer’s gray overalls, was adding final touches to a dense web of pony beads, shoestrings, netting and colored rods that hid the mural his partner had asked him to make. That weird, unexplained cancellation has a poignancy that suffuses “Mammoth,” despite its surface sparkle.

The show’s title, Cave tells me, began as nothing more than an adjective describing the scale and scope of his project. But then he thought about the vanished beasts the word points to, as a noun, and decided to add those tragic creatures to the mix. Above his vast table at SAAM loom five lifeguard chairs, each topped by a crazy-tusked sculpture that recalls a mammoth’s head, as though the planet’s past is watching us threaten its present. Deploying one of his classic oxymorons, Cave talks about his chair-mammoths as both surveilling us and “alarming — signaling us.”

In a gallery off to one side, he’s bringing the lost creatures to life: Projectors will fill the walls with disjointed footage of vast mammoth puppets, making their woolly way through our world. On Oct. 24, performers will animate those mammoths once again, in a procession through SAAM (the show runs through Jan. 3, 2027).

There’s a chance, Cave says, that if our moment’s cultural politics do intrude on his show, the darkness of those mammoths might spread beyond them: “If there was any tampering with my exhibition, I would love to come and spray paint everything black” — like dressing his project in mourning, he says. “All the objects on the table — everything would be just sprayed black. So that may have to happen, yet. And I’m all about it.”

The post The Artist Nick Cave Couches His Critique in Dazzle appeared first on New York Times.