A. P. D. G. Everett is a graduate student in biomedical engineering at the University of Vermont.

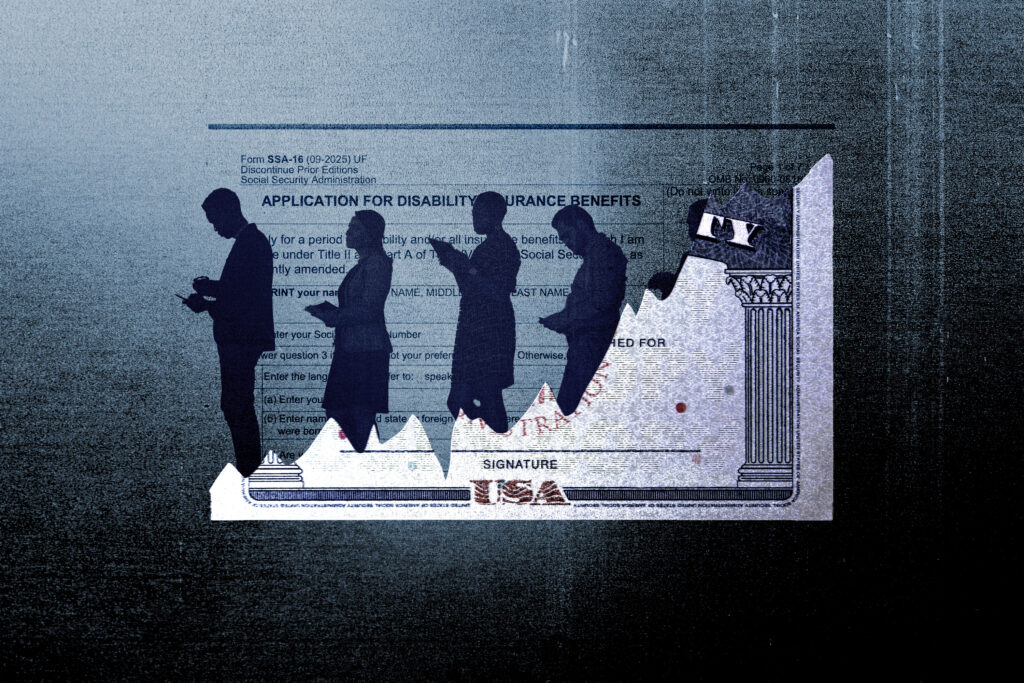

Social Security’s “disabled adult child” program has a simple rule: Someone who suffers a disability before age 22 can claim benefits on the basis of a parent’s earnings record, because they are not considered to have reached economic adulthood. But if the disability occurs after their 22nd birthday, they are on their own, even though young adults have not generally worked long enough to receive meaningful benefits.

That rule once made sense. It no longer does.

The age-22 cutoff reflects a mid-20th-century assumption about how adulthood unfolds — one in which education ended at 18, full-time work began immediately and economic independence was typically achieved by the early 20s. Disability before that point plausibly meant a person never had a realistic opportunity to enter the labor market.

That life course is no longer typical — and Washington already acknowledges this in other policy domains.

Today, undergraduate education routinely extends to age 22 or 23. Graduate, professional and credentialing pathways can delay stable employment well into the mid- to late 20s. Even among those who leave school earlier, insured status is often not available — because it now takes longer to accumulate sufficient earnings credits to qualify for meaningful coverage.

Federal policy elsewhere has already adapted to this reality. Under the Affordable Care Act, young adults have been able to remain on a parent’s health insurance plan until age 26. That law reflected actuarial analysis, modern education patterns and contemporary judgments about when adulthood is realistically achieved.

Social Security, by contrast, remains frozen in an earlier model. The result is not dramatic failure, but quiet misalignment: Individuals whose disability occurs during what is now a normal transition period are classified using rules designed for a life course that, as Gen Z matures, has largely disappeared.

Importantly, updating the age cutoff would not require Social Security to abandon its core design principles. Because the program operates at a massive scale, it must depend on bright-line rules. Age thresholds exist because they are administrable, predictable and resistant to subjective judgment. Raising the cutoff from age 22 to age 26 preserves those virtues while aligning the rule with modern education and labor-market timing that Social Security insurance already implicitly assumes.

This would not redefine disability, expand survivor benefits indiscriminately or introduce individualized adjudication. It would simply place Social Security within the federal government’s own recognition of today’s young adults’ later transition to independence.

Nor would this change be sweeping in fiscal terms. The affected population would be limited to individuals whose disability occurs during a narrow window that modern education and labor-market norms have already made commonplace.

Crucially, this argument stands on its own. It is not about military service, service-connected disability or special pleading for particular groups. It applies broadly to civilians whose educational and economic trajectories no longer conform to assumptions baked into the Social Security Act more than half a century ago.

Twenty-two once made sense. Today, 26 does.

Updating that rule would not solve every edge case, nor would it eliminate the need for other targeted reforms. But it would bring Social Security’s survivor framework back into alignment with modern adulthood — and with policy judgments Washington has already made elsewhere.

That is not radical reform. It is overdue maintenance.

The post Gen Z’s economic reality calls for new disability-benefit rules appeared first on Washington Post.