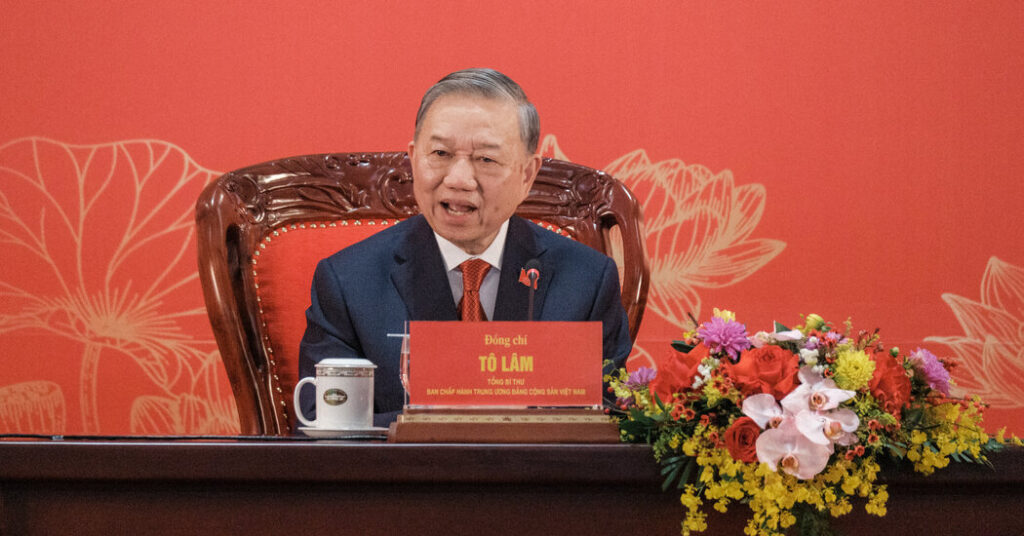

To Lam was already Vietnam’s top leader when last month’s Communist Party congress began. But as it ended on Jan. 23 with him amassing more power, he seemed quicker to smile, to shake hands with comrades in Hanoi’s red-draped convention hall, and in a rush to do more.

At a news conference after the new Politburo list confirmed that he would serve dual roles as head of party and president — a break from Vietnam’s power-sharing norm — he was the first of several officials to enter the room and the first to sit down. His dark wood chair in the center was much larger than the others.

“This congress convenes in a new context, requiring a new vision,” he told a group of mostly state-employed reporters. “This time,” he added, “what’s more important is action.”

Mr. Lam, 68, is now Vietnam’s most powerful leader in decades, consolidating control at a turning point for Asia, with Washington focused elsewhere and Beijing trying to escape a national malaise with dominance in exports and military hardware.

He is not quite like anything this one-party state has elevated before: a former security chief with a Ph.D.; a pro-business reformer; a divorced father of four; a globalist partial to fine wine and Kenny G. And he rose by unusual means: not through compromises among the ruling party’s top ranks and factions, but by insisting that he could make Vietnam a rich, developed country by 2045 — and cutting down rivals to build a bloc of loyalists who owe their fate to him.

He became party secretary in 2024 after leading the Ministry of Public Security during an anti-corruption drive that sidelined other contenders. Then he expanded his reach with an overhaul of government, consolidating 63 provinces into 34 and enforcing party rules that say provincial leaders cannot come from where they hold office, clearing space for allies.

He outlined his vision in Politburo resolutions that prioritized technology (Resolution 57), made private enterprise the economy’s driving force (68), declared that Vietnam’s laws must serve business rather than control it (66), and pushed foreign policy further toward proactive “international integration” (59).

They are widely seen as the most significant overhauls since Vietnam’s economic opening in the 1980s — if implemented. Mr. Lam’s critics fear his style is closer to autocratic cronyism, noting that he is quick to detain critics and already favors politically connected conglomerates with low productivity or high debt from overbuilding housing that few can afford.

With the window of free trade closing under heavy American protectionism and China’s export subsidies, Mr. Lam’s clock is ticking. He said action plans are coming, with deadlines.

“He’s trying to generate excitement,” said Tuong Vu, the director of the U.S.-Vietnam Research Center at the University of Oregon, “and grab as much power as possible in the process.”

Full of Surprises

Who is Mr. Lam, what does he really want, and what will he do if he does not get it?

Vietnamese leaders, since Ho Chi Minh’s campaign for independence in the 1940s, almost never agree to unscripted media interviews. This article is based on conversations with dozens of officials, business executives and diplomats, along with a review of Mr. Lam’s writing and speeches. Many who have experience with Mr. Lam requested anonymity to speak freely about a leader whose career was shaped by policing dissent, and he has not responded to repeated requests for an interview with The New York Times.

Mr. Lam is at this point known for being neither doctrinaire nor charismatic. He is charming in small groups. He is willing to take big risks while keeping his full intentions hidden.

He was born in 1957, in Xuan Cau — an ancient riverfront village in Hung Yen Province, southeast of Hanoi — to parents who were Communist revolutionaries. The family was large and poor, living like most in a house with a thatched roof.

Neighbors from Mr. Lam’s early years said he could often be found along the village road, paved with slanted bricks that were centuries old, heading to the rice fields to catch and eat crabs, snails and fish as well as rats, a local delicacy.

He was remembered for being social and studious, but not the village’s best student.

His father, Col. To Quyen, spent most of the war in South Vietnam, as a security officer for the Communist resistance, before becoming the police chief of the family’s home province. He was not a high-level official, but when Mr. Lam enrolled in 1974 in the government academy that is the main training ground for security elites, he arrived with a legacy to uphold.

“To Lam was one of the ‘princes,’” Mr. Vu said. “So he was a lot more ambitious.”

State security officials, insisting on anonymity, described his rise as far from inevitable. Through the 1980s and 1990s, they said, Mr. Lam struggled to stand out. His operational skills were weaker than those of accomplished peers. He made up for it by building relationships, especially with superiors, leading to jokes that he spent more time at his bosses’ houses than his own.

He expanded his network in part through political training courses. He earned a Ph.D. in law in Vietnam. He also benefited from the Ministry of Public Security’s near-constant restructuring as Vietnam grappled with rapid growth and the internet.

His worldliness and taste for the good life, the first thing that Westerners who know him often talk about, developed through work and marriage.

In the late 1990s, he divorced his first wife, a woman he knew from home, and married Ngo Phuong Ly, a television producer and painter from a prominent artistic family.

In 2008, Mr. Lam was one of 11 deputy directors of General Department I, code-named A11 — a critical unit for national security. His boss was just a year older, considered operationally superior. And the party then had a two-child limit while Mr. Lam had four: a son and daughter with his first wife and two more daughters with his second.

During this period, he often went alone to the National Academy of Music’s concert hall to listen to student performances. His work with A11 also brought him into frequent contact with foreign officials, and in August 2010, he managed to become a deputy minister of public security with a portfolio that included joining senior leaders on trips overseas.

Current and former diplomats described their discussions with Mr. Lam in these years as wide-ranging. Understanding more English than he speaks, Mr. Lam was mild-mannered — when pushed, he often avoided a curt no, hinting at maybe with an “mmm, mmm.” He also signaled that Vietnam should be open to the world, and especially to the United States.

Tom Vallely, the former director of the Vietnam Program at the Harvard Institute for International Development, said Mr. Lam made sure that the 2017 Ken Burns documentary series about the Vietnam War could be seen within Vietnam, without censorship.

Ted Osius, the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam from 2014 to 2017, recalled being surprised when Mr. Lam brought up trade in their first meeting in Hanoi, and in many that followed.

“To Lam was way more than a cop,” said Mr. Osius, who now does business and teaches in Ho Chi Minh City.

Mr. Lam was a disciple of then-Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung, a southerner who had ushered Vietnam into the World Trade Organization in 2006. He and Mr. Lam pushed for President Barack Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership — a free trade deal, rejected by President Trump in 2017, that had been designed to help secure the United States’ place in the region.

Mr. Lam also loved discussing history. He referred often to the Vietnamese generals who in the years 938, 981 and 1288 resisted China and Mongolia’s attempts to dominate Vietnam with a covert strategy of drawing enemies in, then defeating them with iron-tipped stakes in the Bach Dang River, east of Hanoi.

The giant spears were hidden by the high tide. When the water receded, China’s heavy ships self-impaled and sank.

“To Lam was very aware of this idea,” Mr. Osius said. “Use the weight of your enemies against them.”

The ‘Blazing Furnace’

In 2016, Mr. Lam took over the Ministry of Public Security in a party reshuffle. Mr. Dung resigned — his attempt to stay on as prime minister had failed. So Mr. Lam became the top cop for Nguyen Phu Trong, a strict Marxist-Leninist, who was re-elected as general secretary.

Mr. Trong’s “blazing furnace” anti-corruption drive brought them closer together.

In 2017, according to government officials, Mr. Lam directed a high-risk operation to apprehend Trinh Xuan Thanh, a former official accused of embezzling from a state-owned company. Mr. Thanh had fled to Germany and sought asylum. German prosecutors said Mr. Thanh was kidnapped in Berlin by Vietnamese agents and smuggled through Slovakia — where Mr. Lam was at the time.

The case — yielding a life sentence for Mr. Thanh — significantly helped Mr. Lam win Mr. Trong’s trust. Party officials said he gave Mr. Lam the “sword of anti-corruption.” And like the generals of old, he let his most prominent victims fall onto it with their overconfidence.

They were Communists caught up in a capitalist boom. With Vietnam’s rapid growth, it was an open secret that many officials had their hands in the honey pot of business deals.

Mr. Lam faced a scandal of his own in 2021, when a YouTube video showed him in London with other officials, being fed hunks of meat by a celebrity chef known as Salt Bae, who is famous for serving up steaks wrapped in edible, 24-carat gold leaf.

Officials with knowledge of Vietnam’s internal workings said President Nguyen Xuan Phuc wanted him disciplined. Mr. Lam fought back.

Mr. Phuc was forced to resign in 2023 amid a cloud of corruption accusations. Mr. Lam went on to strip Mr. Phuc of all party titles.

His humiliation fit a pattern. In early 2024, as Mr. Trong, the party chief, was on his death bed, Mr. Lam’s anti-corruption effort pushed out every other candidate for Vietnam’s top job.

Mr. Lam became president that May. And when Mr. Trong died two months later, Mr. Lam also became party leader — a dual role, temporary then, now secured for his five-year term.

New York and Trump

Foreign affairs was one of Mr. Lam’s early priorities. He paid a state visit to China in August 2024, a pro forma first stop after taking office in Vietnam, and then he went to New York the next month for the United Nations General Assembly.

His schedule there included a visit to Columbia University to speak and take questions — a rarity for any leader of a one-party state. And before taking the stage at Low Memorial Library, he met privately with scholars and executives in engineering and business. They had been pulled together by Lien-Hang Nguyen, a historian at Columbia, and Mr. Vallely, a Vietnam War veteran and postwar reconciliation advocate, who had moved from Harvard to Columbia.

Several people in the room said the vibe was energetic and urgent. They were impressed by Mr. Lam’s passion for development ideas and his push for research to arrive quickly.

Three months later, he unveiled Resolution 57, the first of his “four pillars.” It identified regulatory bottlenecks as the primary obstacle to technological breakthroughs and looked to some like a clear invitation to global business.

“I was banking on To Lam being a reformer,” said Ms. Lien-Hang, who had left Vietnam as an infant, with relatives who were citizens and soldiers of the fallen South Vietnamese government. “And he definitely is.”

Mr. Lam’s advisers hoped he would leave the same impression with the man about to become president: Donald Trump. Mr. Lam’s office had requested a meeting before the trip.

The day after Mr. Lam’s Columbia appearance, on Sept. 24, Mr. Trump appeared at a signing ceremony involving his son Eric Trump and a Vietnamese developer who paid millions for the rights to build a Trump golf complex in Mr. Lam’s home province.

The president-to-be snubbed Mr. Lam.

Tariffs followed in 2025, sky high, then reduced to 20 percent after entreaties from Hanoi. After the White House added levies on furniture, a priority industry for Vietnam, Mr. Lam privately expressed frustration and confusion, according to officials in meetings with him.

Yet he did not give up. Vietnam was among the first countries to sign up for Mr. Trump’s “Board of Peace.” It has finalized deals to buy C-130 transport planes and Sikorsky helicopters from the United States, according to officials, who said Mr. Lam hopes to announce the purchases at a high-level visit, which Washington has not yet approved.

Some of his critics from a Marxist bent worry that Mr. Lam might be Vietnam’s Mikhail Gorbachev, a reformer who takes down the system by upsetting the traditional balance of power, sidling up to Washington and moving too quickly with oligarchs at state-favored companies.

Those hoping for more freedom of expression fear he will be another Xi Jinping, hardening with time into a rigid party autocrat.

He has already overseen myriad, tough crackdowns — on environmentalists, social media influencers, a journalist who wrote that “a country cannot develop based on fear,” and in 2023 on a Vietnamese activist who spoofed Mr. Lam’s meal of gilded beef by making a video that showed him theatrically sprinkling onions onto a bowl of noodles.

The activist was convicted of producing anti-state propaganda and sentenced to more than five years in prison.

‘A New Approach’

At the news conference, Mr. Lam seemed especially proud when describing how he had boiled down three long documents that emerged from prior congresses into one brief summary.

“We need a new approach,” he said.

Among scholars and officials, the main questions now are: Will his changes work, and are they going to be about him or the entire country?

Vietnam’s economy has grown steadily since the 1990s, but its population of 102 million risks getting old before getting rich. Higher education lags behind that of regional peers. Air pollution is worsening. A surge of Chinese factories in Vietnam threatens to rankle Mr. Trump’s trade enforcers and, along with a flood of Chinese imports, stunt Vietnam’s push for manufacturing expertise.

Mr. Lam hometown’s of Xuan Cau stands as a monument to his ambitions and risks. His small family home is now a compound with several expansive buildings behind pale yellow walls, surrounded by new schools, roads, soccer fields and a once-polluted pond that is now clean.

Nearby, cranes rise over a huge, residential and commercial development painted in crayon colors with plazas holding mock-ups of Italian statues — a Vietnamese Epcot Center.

These used to be some of the rice fields where Mr. Lam searched for food.

On a recent visit, the bright lights visible from a new highway prophesied cheer, but up close, hundreds if not thousands of completed luxury villas sat dark and empty.

All of Vietnam is waiting for Mr. Lam to succeed.

Damien Cave leads The Times’s new bureau in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, covering shifts in power across Asia and the wider world.

The post Vietnam’s Leader Has New Power, and He’s in a Hurry appeared first on New York Times.