This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

At least one fundamental human trait persists in the smartphone era: People seem to love a challenge. The internet teems with viral competitions, gamified health apps, and “life-maxxing” exercises of many kinds. Even those who resist the lure of screens—by, for instance, reading books—are frequently doing so with a kind of competitive zeal. A University of Pennsylvania professor has built a strict, rules-based classroom cult around reading. And this week in The Atlantic, Walt Hunter, who teaches English at Case Western Reserve University, wrote about his own attempt to buck alarming literacy trends by asking his students to read entire books.

First, here are four stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- ASurvivor contestant’s empathetic reality-TV novel

- “One of Our Own,” a poem by Adam Harris

- There is a word for what is happening in Minneapolis

- How to portray a wildly unequal society

Hunter discovered that if you recalibrate a course to prioritize “developing a relationship” with authors and books (he eased up on writing assignments, for example), students will meet the challenge. After he swapped out short excerpts for full texts, his students “were reading everything, or most of it.” They proved it by identifying obscure passages without notes (and, because he quizzed them in the classroom, there wasn’t a chatbot within reach). Even more important, “they were experiencing life in a way that was not easy outside the class.” They were putting effort and time into a mental activity that scrolling on their phone couldn’t match.

This is a feel-mostly-good story, but how useful is Hunter’s experiment for those of us who don’t have anything except our own willpower standing between us and the algorithms? Such readers might find value in anotherAtlantic article this week, in which Bekah Waalkes recommends books that can be read between errands. Waalkes suggests an attitude shift that doesn’t force you to choose between setting strict reading goals and giving up altogether. “All you need,” she writes, “is a willingness to dedicate a few minutes a day, and maybe a few new habits.”

Hunter also describes reading as a feat of adult self-motivation. “You are not word-maxxing or optimizing information for efficiency,” he writes. “You are engaged in a singular practice, one with its own primary justification.” I like the word “practice,” because reading requires it, just like many other things grown-ups find fulfilling. We schedule activities—travel, socializing, cooking, exercise—so we can achieve everything we should do and everything we want to do (two categories that ideally overlap). With time, we get better at these things—and at finding a place for them in our life. So here’s my advice, if you need it: Schedule some reading time, wherever and whenever you can. Pick up one of Waalkes’s recommended books, or whatever you like. Set a timer, dive in, and find out what you’re made of.

Stop Meeting Students Where They Are

By Walt Hunter

What I learned when I finally started assigning the hard reading again.

What to Read

Northanger Abbey, by Jane Austen

Like Austen’s other novels, Northanger Abbey contains a marriage plot. But it’s set apart from the rest of her work by a long, satirical section sending up gothic fiction and its fans. The book’s heroine, Catherine Morland, is an avid reader of the popular novels of the day, and has a specific fondness for Ann Radcliffe’s real-life 1794 best seller, The Mysteries of Udolpho, a tale of ghostly figures and hidden manuscripts. Catherine views herself as the hero of a similar story, and when she goes to the country house of a family she has befriended (the titular Northanger Abbey), she reinvents herself as the protagonist of a mystery. Austen is the master of depicting small faux pas, and Catherine commits many—she forces open cabinets in search of creepy documents; she begins to suspect that the family patriarch has murdered his wife. The chronic daydreamer can easily identify with Catherine’s near-delusional longing for something to happen beyond the courtships and evenings around the pianoforte that seem to make up the better part of her future.

From our list: Six books you can get lost in

Out Next Week

Eradication, by Jonathan Miles

Eradication, by Jonathan Miles

Frog: and Other Essays, by Anne Fadiman

Frog: and Other Essays, by Anne Fadiman

The Mixed Marriage Project, by Dorothy Roberts

The Mixed Marriage Project, by Dorothy Roberts

Your Weekend Read

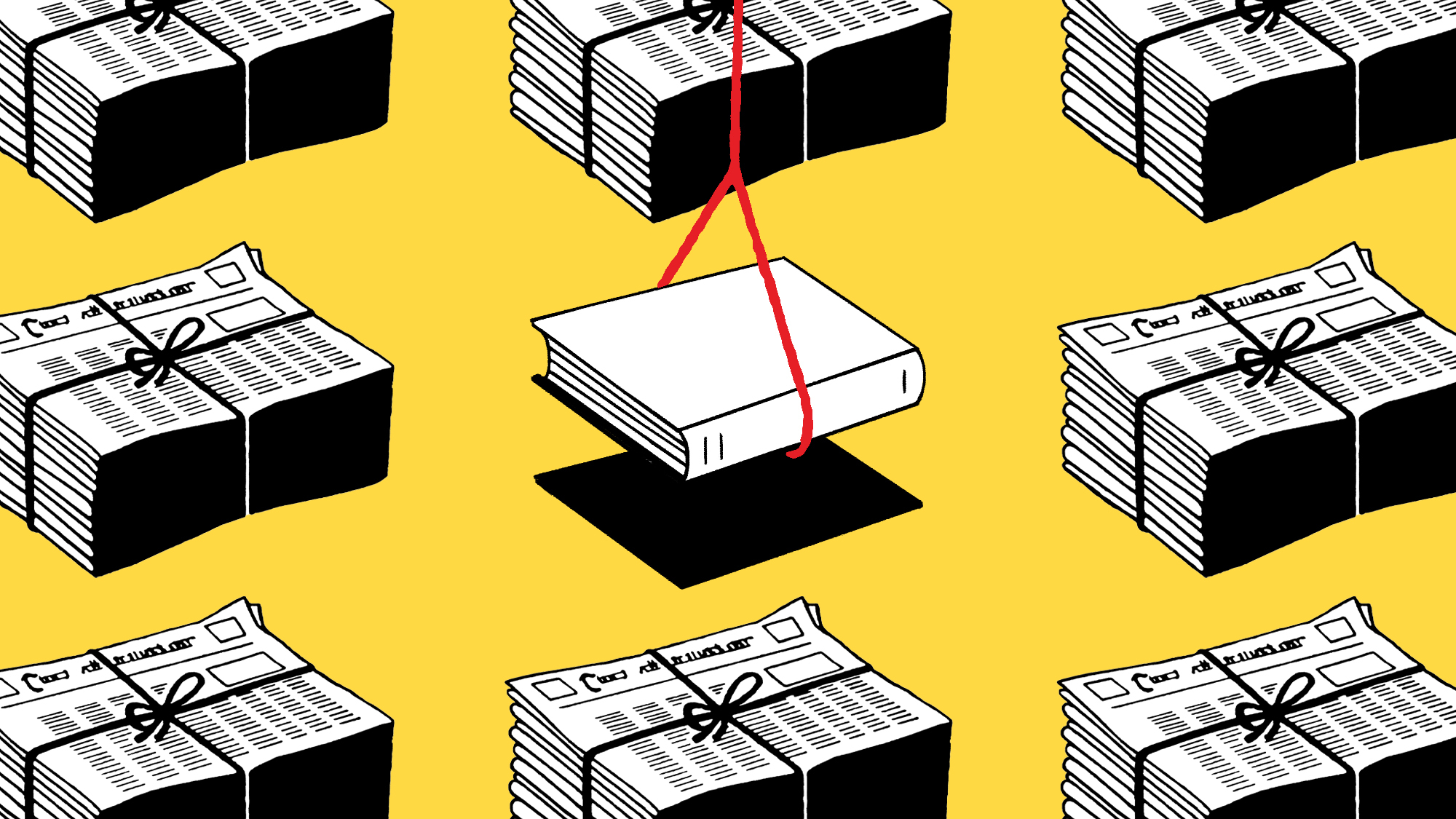

What Happens When Books Aren’t News

By Adam Kirsch

With this week’s announcement of massive cuts at The Washington Post, the paper’s Book World supplement earned a dismal distinction: It may be the only newspaper book-review section to have been killed twice. The first time was in 2009, when papers across the country were slashing books coverage in an attempt to stave off budgetary apocalypse. So when the Post relaunched Book World in 2022, readers and writers reacted with the same mixture of amazement and trepidation inspired by the dinosaurs at Jurassic Park. The rebirth of a dead species was wonderful to see, but how would it end?

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.

The post Reading Is a Practice, Not a Chore appeared first on The Atlantic.