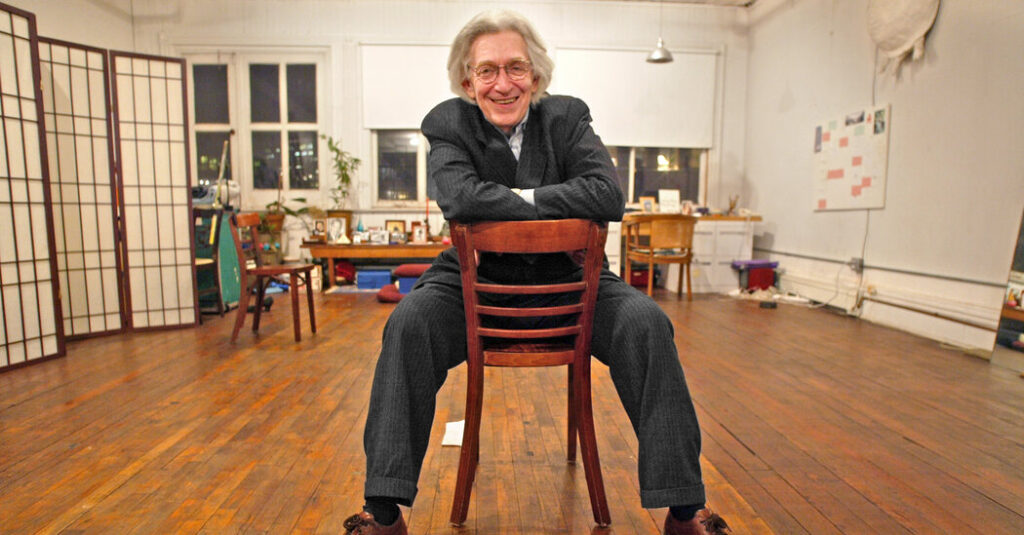

Ted Berger, the leader of an arts advocacy organization in New York City that invested millions of dollars in what he called “the possibility of people,” championing an impressive roster of artists including the composer Meredith Monk, the filmmaker Spike Lee and the director Julie Taymor, died on Jan. 29 in Manhattan. He was 85.

His death, in a hospital, was confirmed by his son, the artist Jonathan Berger.

“We, the artists, are the facade of what Ted has built here in New York,” Ms. Monk told The New York Times in 2006, when Mr. Berger retired from the New York Foundation for the Arts, the nonprofit organization he led. “And Ted is our foundation.”

Mr. Berger joined N.Y.F.A. in 1973, two years after it was established, and became its executive director in 1980. Over the next quarter century, he oversaw the organization as it doled out nearly $23 million in fellowship grants to mostly young, struggling and underrecognized playwrights, novelists, filmmakers, photographers, composers and other artists.

Tony Kushner, who received a grant in 1987 while he was working on his epic play “Angels in America,” told The Times, “I’ve always considered Ted and the people at N.Y.F.A. patron saints of the American theater.”

Mr. Berger spoke about the inspiring effect of sitting in on panels evaluating the work of artists who had applied for grants.

“When I was at N.Y.F.A. and in the middle of paperwork and budgets,” he told the Grantmakers in the Arts website in 2013, “I’d just go into the fellowship panels and sit and listen and see the work. It is very humbling and a constant reminder about whom we serve.”

Under Mr. Berger, N.Y.F.A. supported causes like health insurance for artists and arts education in schools. It also provided artists with free work space, and defended them in the late 1980s and early ’90s when Congress slashed funding to the National Endowment for the Arts over artwork deemed indecent or worse.

“Artists are always probing boundaries, and they always will,” Mr. Berger told The Times in 1989. “But government support is supposed to be about freeing ideas and opinions.”

In 2001, N.Y.F.A. created One Step Forward, a fund to help dancers with serious health problems; the initial funding came from a benefit that featured performances by 12 dance companies. The first beneficiary was Homer Avila, whose lack of insurance had delayed the amputation of his cancerous right leg and hip. Mr. Avila, who learned to perform on one leg, died in 2004.

“The realization of the health insurance crisis for artists also led Ted, who always formed coalitions, to create the Artist Access program through Woodhull Hospital,” Edith Meeks, a former assistant to Mr. Berger, said in an interview.

Ms. Meeks described Mr. Berger as “an artists’ first responder” because of his concern for artists’ welfare.

“He was always moving very fast,” she said, “so I was always following him, dashing down the hall. If you wanted to say something to him, you had to cut it to its essence.”

Theodore Sheldon Berger was born on July 9, 1940, in Providence, R.I., the only child of George and Freda (Simon) Berger, a bookkeeper.

As a child, he enjoyed reading the building plans that were published in the Sunday newspaper, and he briefly considered a career in architecture. Instead, he studied literature at Dartmouth, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1962. Three years later, he received a master’s degree in English and comparative literature from Columbia.

In 1964, he ventured into musical theater, as the librettist and lyricist of “Shoemakers’ Holiday” — Mel Marvin composed the music — based on a 1599 comedy by the playwright Thomas Dekker. After opening at Barnard College, it was produced Off Broadway in 1967.

By then, Mr. Berger was an assistant dean at Columbia, but he resigned over the university’s response to the 1968 protests that convulsed the campus and ended in a violent melee when police removed students occupying five buildings.

After about five years without work, he was hired at N.Y.F.A. in 1973 to coordinate a program that brought the arts into New York State’s public schools at a time when resources for arts education were being cut.

Bringing artists into classrooms — for performances, residencies and various projects — was a passion for Mr. Berger, who was also a founding director of ArtsConnection, which has provided arts programming to New York City public schools since 1979. He continued in that role until his death.

“He was the guy you turned to at meetings for advice, common sense and perspective, because he was involved in so many things,” Steve Tennen, who was the executive director of ArtsConnection for 34 years, said in an interview. “He helped invent arts education in New York State.”

Mr. Tennen credited Mr. Berger with persuading city schools to make partial payments for programs provided by N.Y.F.A., and with negotiating a merger between ArtsConnection and High 5, a struggling organization that sold students discounted tickets to arts events.

Mr. Berger helped start the Cultural Council Federation Arts Project, a jobs program funded by the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. From 1977 to 1980, the project employed 325 artists in New York City.

He was also a director of the Joan Mitchell Foundation, which in its infancy used office space at N.Y.F.A. In 2015, he advised the foundation on the creation of artist residencies at a center in New Orleans and on a legacy program that helps artists document their works and develop estate plans.

“He was incredibly generous and thoughtful, and asked relentlessly if we can do more for artists,” Christa Blatchford, the foundation’s executive director, said in an interview. “He always had new ideas as he was watching the field.”

In addition to his son, Mr. Berger is survived by his wife, Asya (Eliash) Berger.

Supporting creators and letting them focus on their work was his overarching vision. “By helping these artists,” Mr. Berger said, “we are saying to them, ‘You have a right to dream.’”

Richard Sandomir, an obituaries reporter, has been writing for The Times for more than three decades.

The post Ted Berger, Indefatigable Patron of Artists and Schools, Dies at 85 appeared first on New York Times.