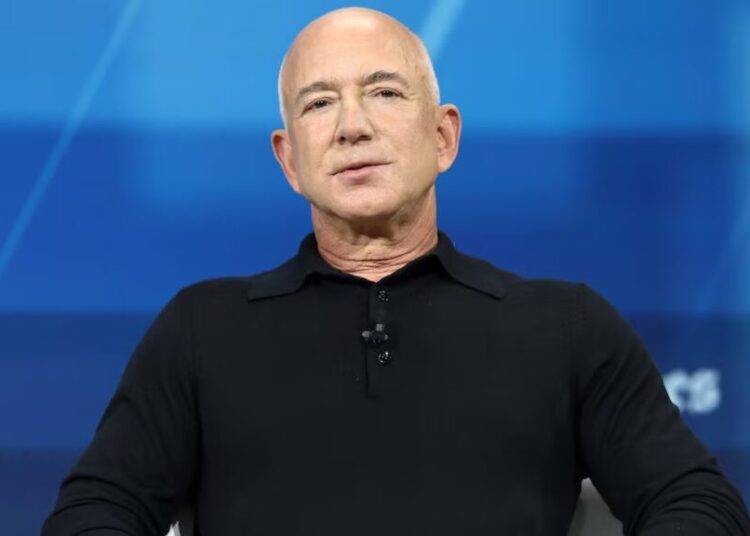

As I talked about awards season with Stellan Skarsgard last month in Los Angeles, an industry voter interrupted our lunch to express his support.

“You are so overdue of the major awards, and I’ll be voting for you, that’s for sure,” the man said. “I really, really hope you win.”

“Thank you,” Skarsgard replied. “I hope I’m not overdue in everything.”

It may seem surprising that Skarsgard, 74, received his first Oscar nomination only two weeks ago, for the Norwegian family drama “Sentimental Value,” since he has worked consistently in high-level fare for decades. After beginning his career in Swedish television, Skarsgard scored an international breakthrough with Lars von Trier’s 1996 drama, “Breaking the Waves,” which led to roles in the Hollywood productions “Good Will Hunting” and “Amistad” the following year.

Since then, he’s balanced parts in mass-appeal franchise fare like “Dune,” “Mamma Mia!” and five Marvel films with notable turns on television, earning awards attention for his performances in “Chernobyl” and “Andor.” Still, he has never had a moment quite like the one now afforded to him by “Sentimental Value.”

Directed by Joachim Trier (“The Worst Person in the World”), the movie casts Skarsgard as Gustav Borg, a self-involved filmmaker who prioritized his career over his family, alienating his eldest daughter, Nora (Renate Reinsve). Believed to be past his artistic prime, Borg attempts a comeback with a deeply personal new film that he hopes Nora will star in. But when she resists, he instead casts an American actress (Elle Fanning) who can’t quite grasp the family’s long-buried pain and resentments.

Nominated for nine Oscars, including best picture, “Sentimental Value” has become a major player this awards season, earning Skarsgard a supporting-actor Golden Globe. Still, he approached the movie with some concerns. Four years ago, Skarsgard had a stroke that impaired his ability to memorize lines and he must now wear an earpiece on set, with dialogue fed to him by a prompter.

“In general, I don’t think I lost much quality of acting in that process, but it’s good to have lines in your ear because you can be precise about it,” he said, acknowledging that memory issues still frustrate him: “When I’m talking to you like this, you see I lose the line of thought and it annoys me enormously.”

Though I understood his self-consciousness, I noticed no such lapses. Quite the contrary: Over our hourlong lunch, Skarsgard was sharp and opinionated as he discussed the promotional demands of awards season and his anxieties about the current state of filmmaking.

Though he believes that money and corporate consolidation have imperiled the ability to do great work in Hollywood, there’s still no industry Skarsgard would rather be part of. “Film is the last remaining vaudeville in the world, the last remaining safe place for weirdos and outcasts,” he said.

Here are edited excerpts from our conversation.

Do you often spend this much time in L.A. when you’re not working on a project?

No.

Although I suppose this awards season is a project of sorts, isn’t it?

This is a role like any. But I don’t know. It’s not the kind of role I normally like.

Because you have to play yourself, in a way?

Yeah, in a way, but even that I can do. I have no problem with meeting people, but it’s the scale of everything, and the money. There are so many award shows that [don’t] mean anything, so you’re only there as a celebrity, and some people have it as an income.

Awards season is a whole ecosystem.

I don’t mind the ecosystem because it’s essential for the independent films that can’t afford to pay the normal marketing money. When “The Godfather” premiered, it grew because people liked it, not because they liked the advertising. It’s sad. Everything is monetized, everything is for sale. In the art world, it’s the same: The difference between the money that is paid for the art and the quality of the art is enormous compared to what it was.

What do you attribute that to?

We have a system that is so based on greed. We are also teaching a generation now that the only way to survive in this world is to be greedy and that self-promotion is the thing to do, but I don’t think it is. If you’re a good artist, you should not have to be a good self-promoter.

Of course, this awards season requires some self-promotion. That can lead to great conversations, though sometimes I’m sure it feels more like speed dating.

My press people are protecting me from the speed dating, I’ve been very lucky. And I don’t have social media.

So this is as close as you get, in a way.

This is as close as I get to TikTok. [Pause.] I don’t want to sound … I mean, we got started on the wrong foot, in a way.

Were you going to say you don’t you want to sound ungrateful? I don’t think you do.

No, I’m so grateful for the opportunity to do what I like, but I see it threatened all the way. Every [expletive] thing I love about it is threatened. Joachim, he’s one of those original people that are almost extinct because the system doesn’t allow them to live in this world.

How so?

There’s something revolutionary about a film that has that truthfulness and sincerity in describing the characters, but also a lightness. And it’s not loud. When everything screams at you, everything is in bright colors and fiercely attacking you to make their money, it’s so nice to hear someone who’s sincerely and without calculation presenting something so truly original and subtle and also humanistic.

You once called acting the most frightful job you can imagine. What was most frightful to you about doing “Sentimental Value”?

Well, I had practical problems because I had a stroke. I had to invent a method of getting the prompter to function. I think it went well. I mean, I did it in the last season of “Andor” and “Dune” as well, with varying success. But in general, I don’t think I lost much of quality of acting in that process.

Do you think you would have returned to work as quickly after your stroke if it weren’t for your prior commitments to “Dune: Part Two” and “Andor”?

I don’t know. I might have fallen into a despair and eventually not have had the courage to try it again. But I had to do it, and both Denis Villeneuve [director of the “Dune” movies] and Tony Gilroy [creator of “Andor”], their support was fantastic. They said, “Come in. Take your time.”

With “Sentimental Value,” you’re entering a milieu that is established, where Joachim has worked with some of the other actors before and has established a tone to his work. Do you like to adapt to that, or do you prefer to pull that in your own direction?

It’s interesting that you say it because I didn’t have it as a clear thought, but of course it is like that. But I’m also the kind of actor that is extremely adaptive to the world of the director because it has to have a clear center, it has to be his universe. That doesn’t mean that you can’t collaborate, but he has to be the man who chooses. It’s different, of course, if you do a Marvel film, which is an industrial production where you don’t know who the director is, anyway.

I’m the most experienced in this cast, and I know more than most directors about filmmaking. But my philosophy is that everything I know is worthless, in a way.

How do you mean?

Because I don’t know how this film will be made. It’s like when I started working with Lars von Trier, if I would have said to Lars, “You cannot cut that way, you can’t have people crossing the line with their gazes,” it would have been ridiculous. And that’s what he did. But there might be a first-time director who has an idea about the film that is new to me, and I don’t have any idea about the value of it, and I cannot correct him.

When someone comes up to you this season and praises you, what do you make of it?

It’s fantastic because I’ve touched them, I’ve had an impact on their view of life. If nobody notices you, it’s very hard to be an actor. But Milos Forman once said to me, “I’ve seen you several times, and I didn’t know who you were.” He thought of me as someone who was always doing the role perfect, but my own personality wasn’t there. So I saw it as a compliment and insult.

I assume, then, that you’ve never felt typecast.

No. I mean, the last four projects I’ve done, I look completely different. From the fat guy in “Dune” to the wigs in “Andor” and this one. I come from theater, so you’re used to wigs and doing several different characters, especially when you start out. There’s a childish satisfaction of becoming an invented person.

Which reminds me of your recent W magazine article, in which you dressed in drag. How did that come about?

It was their idea, and I went for it. I’ve seen my son do it with success. And I dressed the first time in drag when I was 15 years old.

Was it for a role, or …?

No, no, I just borrowed a girlfriend’s clothes, and I put socks in the bra and put on makeup and went out. I was flabbergasted over how young men were treating me — the notice you got and the eyes and everything. It was a very different experience. So I know that it can be seductive and also objectifying to be a woman.

Did you have major Hollywood aspirations before your breakthrough in “Breaking the Waves”?

For years, I didn’t want to get out here. I didn’t come in and shake hands. “Why? They can look at my films.” In a way, it was naïve and snobbish, and I had a lot of good films to do in Europe. Eventually, I came out here and I liked it, but I wasn’t depending on it. I could visit Hollywood without needing it.

It didn’t become your center of gravity.

No, so it was very comfortable. I had no problem saying no, or just being curious. I was asking, “Oh, you’re a casting director. What do you do?” I didn’t know. We didn’t have any casting directors.

Sometimes international actors have an acclaimed film that puts them on Hollywood’s radar, but then they never make anything as singular as what got them there.

Yes, but it’s always hard to find good roles. About every 10 years I’ve had one. And that’s good.

Kyle Buchanan is a pop culture reporter and also serves as The Projectionist, the awards season columnist for The Times.

The post Why Stellan Skarsgard Wasn’t Sure He Could Handle ‘Sentimental Value’ appeared first on New York Times.