In 1975, Anne Elizabeth Howes — a young actress from Birmingham, Mich., who went by Libby — landed in New York. The city wasn’t at its most hospitable that summer: City Hall teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, and, in July, the Sanitation Department briefly stopped picking up the garbage. But Howes was a pilgrim, dedicated to new forms of performance, so she came East to intern with a collective of avant-garde artists that included the actor Spalding Gray.

By October, the 20-year-old Howes was performing in “Sakonnet Point” (1975), the first piece in the “Three Places in Rhode Island” trilogy, made by what would eventually be called the Wooster Group. Howes would appear in all of these productions, a set of hallucinatory evocations of Gray’s past, including “Nayatt School” (1978) and an epilogue, “Point Judith” (1979) — but she especially shone in “Rumstick Road,” the second piece of the Gray triptych.

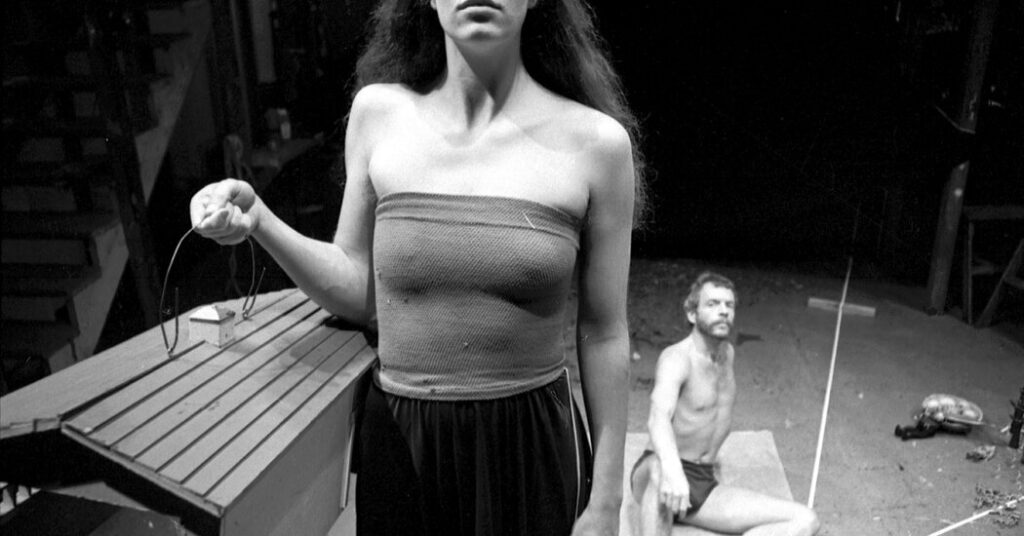

“Rumstick Road,” from 1977, is a part-documentary, part-vaudeville, part-nightmare in which Gray recounts the mental deterioration and eventual suicide, in 1967, of his mother, Bette. Actors lip-synced to recordings of his family members or ran around like kids; a cool-voiced Spalding showed slides of his childhood home, where his mother lost her mind. Howes — an instinctive dancer and an imposing presence onstage — played an archetypal “Woman” figure. She was simultaneously Bette, and not-Bette, and the Bette that no one knew.

I was born around the time “Rumstick Road” went into rehearsals, and so I only encountered it 35 years later, in a so-called video reconstruction, a complex assemblage of footage from various performances, reel-to-reel audio tape and even photographs. The director Elizabeth LeCompte and the filmmaker Ken Kobland first showed this gorgeous film-compilation in 2012; I saw that screening, and it remains one of the most extraordinary theatrical performances I’ve ever seen, live or recorded.

An exhilarating, contagious energy somehow breaks through the patchwork of bleary Kodachrome. In one astonishing sequence, Howes performs what LeCompte called the “house dance,” the obsessive repetition of a single headbanging movement, set to a stormy Bach partita for solo violin. The actress looks like a figure out of gothic horror: She wears a long, dark, Victorian dress and, as she bends again and again, her waist-length hair whips back and forth like a cat-o’-nine-tails. This percussive rocking goes on for 10 minutes. I remember thinking, this is dangerous.

“Rumstick Road” was a legacy-building triumph for the Woosters, which just celebrated 50 years of making genre-dissolving work under LeCompte’s direction. They are the first of the great multimedia collagists: Pieces seem to switch channels among dance, panel discussion, explicit B-movies, deconstructed theatrical texts, and — presented with equal dispassion — their own lives. In the 2025 book “American Performance in 1976,” the scholar Marc Robinson names the first public rehearsal of “Rumstick Road” as one of five landmarks that established an American avant-garde. Watching the film, it’s clear that Howes — so often noted by critics for her beauty and ardency — was a major reason why.

But the reconstruction can also be painful to watch, for those who know what came after. In “Rumstick Road,” for example, we hear Bette’s psychiatrist telling a bewildered Spalding not to be frightened of depression’s “hereditary predisposition.” We know that in 2004, Spalding will die by suicide. Ron Vawter, who played Spalding’s father, died in 1994, his heart weakened by AIDS. And Howes had a psychotic break in 1981 — and disappeared.

For decades, Howes’s location has been a mystery; she has been an unquiet absence, one of the ghosts in the avant-garde’s machine.

A Family of Intellectuals

Libby Howes was the youngest of four tall girls. She and her older sisters — Candace, Priscilla and Margaret (often called Peg) — were all born in Hartford, Conn., but were raised in Michigan, after their mechanical engineer father got a job at Ford. They came from a family of Boston intellectuals: Libby’s paternal grandmother was the suffragist and psychologist Ethel Puffer Howes, who completed a full slate of doctoral work at Harvard in 1898, 65 years before the psychology department awarded its first Ph.D. to a woman.

When Libby came to New York, she was only partway through her degree at the University of Michigan. In 1974, a workshop at the college had brought her into the intoxicating orbit of the Performance Group, a seminal ensemble whose bacchanalian work explored the ritual aspects of the theater. One show, “CLOTHES” (1975), consisted of persuading the audience to strip.

Oskar Eustis, now the artistic director of the Public Theater, remembers meeting Howes at a theater festival in Ann Arbor in May 1975 — she had already secured her Performance Group internship; he was a 16-year-old runaway, hitchhiking around looking at experimental theaters. After following her Pied Pipers to SoHo, Howes bunked on the second floor of the Performing Garage, the Group’s home in a converted metal-stamping plant on Wooster Street. When Eustis arrived in New York that fall, he stayed with her.

“The way these things happen, we became a couple almost immediately,” he told me, and they were together for about a year. Eustis said the two of them were there, interns quietly repainting the Garage, during a fateful meeting when the Group’s leader, Richard Schechner, stormed out, incensed by his insurgent protégées, LeCompte and Gray. They would go on to take over the space and rename the ensemble.

Eustis remembered the “Rumstick Road” performance as a turning point. “It was not something I’d ever seen from the Group under Schechner,” Eustis said. “And Spalding was amazing, but Spalding was doing the New England cool.” It was Howes’s house dance that was the beginning, Eustis said, of what the Wooster Group “has been doing ever since, which is — yes, it’s postmodern cool, but it’s also fierce, intense, personal.”

Wooster Group productions have also been services for the dead. Films and tapes keep long-gone voices present, and props — a red tent, for instance, which Bette takes refuge in at the end of “Rumstick” — are reused through decades of shows. These objects acquire a kind of talismanic heat.

And they broke taboo after taboo. Howes appears in a sequence used in “Route 1 & 9 (The Last Act)” from 1981, a two-minute clip of a black-and-white pornographic film of her and the group’s rising star, Willem Dafoe. Candace was horrified when Howes screened the whole thing for her: “I felt something was unraveling,” she said. (By that time, Gray was shifting focus both to his Hollywood career and to his own hugely influential solo monologue pieces.)

Through the 1970s and early ’80s, Howes worked mainly on Wooster productions; she also started creating her own work, like the immersive “XXX Standing Room Only.” But by the spring of 1981, Howes’s accelerating mental dislocation became impossible to ignore.

Kate Valk, now the grande dame (and co-artistic director with LeCompte) at the Wooster Group, has spoken about the time that Howes, who periodically slept under the risers in the Garage’s theater space, began to perceive mystic correspondences between the “arrivals” at a train station and a mysterious figure — perhaps one of the homeless men she had been inviting inside — she believed was “arriving soon.”

At the time, Valk was herself a young intern, and she had been entranced by Howes’s physicality — “the equal of the men,” she said. But language for Howes had gone fluid and magical, and her bodily strength couldn’t resist these new mental tides. Candace heard from Howes’s boyfriend, the poet Bob Holman, that “she was coming apart. And I said, ‘Well, what’s the evidence?’ And he said, ‘She tried to get on a plane to Amsterdam without a ticket.’” Candace arranged for Howes to be admitted to Bellevue Hospital, and Peg transported her, along with Valk and a few others. It took hours to persuade her to sign herself in.

Valk told stories about Howes in the Group’s most recent work, “Nayatt School Redux” (2025), which — like its ’70s antecedent — takes its charge from the performer’s own memory of a story larger than herself. I asked Valk how retelling this part of Howes’s undoing affected her. Did it alter her appreciation of the past? “Everybody was looking for liberatory practices,” Valk said. “And sometimes that looked like madness, and sometimes it was madness.”

Still, she doesn’t see suffering when she watches those old performances, or danger. “To me, I see, with both Spalding and Libby, that the work gave them a place to live.”

Howes’s parents took her back to Michigan, where she finished her college degree. After a few years, though, she abandoned treatment for her schizophrenia. She became belligerent and chaotic, and at one terrible Christmas gathering, her mother had the police remove her from the house. Her parents relocated to the East Coast, and Howes, in an oblique way, followed. First she returned to New York, living for a time under the West Side Highway, and then she continued moving, migrating to Keene, N.H., where her family had a summer house.

Howes seemed to have been lost to many who had known her. Eventually, she refused to use a phone — and so she became harder and harder to reach.

A Life in Vermont

Many people, though, actually knew right where Libby was. In the ’90s, she moved to Brattleboro, Vt. With a population of about 12,000, the town is uniquely welcoming to those like Howes; she lived a life on her own idiosyncratic terms there that seems nearly impossible anywhere else.

After her mother died, she inherited a small legacy, which allowed her to buy a house that was located, fortunately enough, next to a supportive shelter called Groundworks Collaborative. With a little bit of state assistance and a trickle of money from the trust, she managed to tread very lightly on the earth. She became a constituent, and then a helper, at various places that fed the homeless.

One of her best friends, Curtis Carroll, who went on long hikes with her, said “she was amazing,” but when her language went beyond short exchanges, “it really didn’t make a lot of sense.” He seemed unruffled when she would, say, insist that her sisters were impostors. At one point, she quarreled with Carroll because his license plate started with an AEH. The letters were her initials, and so “she felt like I was stealing her soul,” Carroll said. She secretly repainted his plate; Carroll only realized what she’d done when he came out of a shop to find his car surrounded by the police.

In the last decade, her moods mellowed, a little, and her array of self-made finery and delight in speaking with her neighbors made her a much-loved local figure. “She was more than willing to talk to anybody,” Carroll said. “There are lonely people out there everywhere, but she was interested in them, and they were interested in her.”

When Howes died on Dec. 17, 2025, though, she still maintained a certain mystery. She was Libby, and not-Libby, and the Libby no one knew.

For instance, one of Howes’s sisters, Candace, found herself talking to the man who was set to carve Howes’s headstone. They had been discussing Libby for a while before, in the course of conversation, she pointed across the street to her sister’s yard. The man gasped. “You mean Anne? Anne died?” In 70 years, Candace had never known anyone to call her Anne.

I talked to the Rev. Dr. Scott Couper, the pastor of Centre Congregational Church, which hosted her memorial. “We had probably over a hundred there,” he said. “I’m not sure if that many people would come if I died.” Her life had been richer than even her family and friends had known. Peg met a woman who told her Howes had participated in the Southern Vermont Dance Festival for years. Candace learned she had been singing with an organist, every day.

“Her conventional life really came to an end when she was only 26,” Peg said. “It was really comforting to know she was not isolated, she was not alone.”

A passionate environmentalist, Howes lived without heat and running water, for decades. Carroll described her house as a kind of part wilderness. “The house was so porous — windows were broken, doors wouldn’t shut — that animals started to walk through,” Carroll said. “She was delighted with that.”

A fire partially destroyed the house in April 2025, at which point she moved into a tent in her own front yard. She told Candace that she “absolutely loved it.” Everyone begged her to come inside when it got perilously cold. But she wouldn’t. The words “fiercely independent,” said Minister Couper, sometimes conceal how much frustration that “fiercely” could inflict on those who want to help. She did, at the end, come inside, when cancer took her very quickly. She made one of her only phone calls, from her hospital bed, to thank Carroll for his friendship.

After Howes’s death, the Wooster Group’s archivist Clay Hapaz sent videos and images of Libby to Candace, as well as The New York Times. I have been doing my own private memorial, watching “Rumstick Road,” again and again, and talking about her with Robinson, the scholar, and others who were changed by her work without ever having seen her in person. I’ve started finding mystic correspondences too, like that warmly glowing tent, an image I associated with her for more than a dozen years before I would ever learn she spent the last months of her life in one.

Almost nobody from Vermont knew that she had been an important actor and dancer; and no one from her New York days seemed to have been at her funeral. A few didn’t know she had died until I reached out for a comment, though others posted tributes on her online obituary.

The only character from her short, dazzling career that her friends could remember figuring in the intervening decades was Gray, whom Howes approached after he performed in Vermont. Afterward, Gray told LeCompte that they had a “nice, but short” conversation, though Carroll doesn’t think it was a successful meeting.

But then the other indelible image from “Rumstick Road” is not one of connection. Near the beginning of the show, Spalding and Libby play a manic game of tag as a jazzy Nelson Riddle theme plays. They race like children across the set: Sometimes he is “it,” sometimes she is. Spalding and Libby run through doorways, slamming and opening doors, making only glancing contact, but clearly having a wonderful time. The film flickers, and they fade, but that’s how I remember them: chasing each other round and round forever.

The post The Actress Who Disappeared Twice appeared first on New York Times.