For many Americans, the events in Minneapolis and the upheaval across the country bring to the surface not just political dilemmas but moral and spiritual ones too. How to best defend the things we believe in, how to understand the people we disagree with and how to maintain faith in one another — these are questions I’ve been thinking about even more since I spoke with the Rev. James Martin.

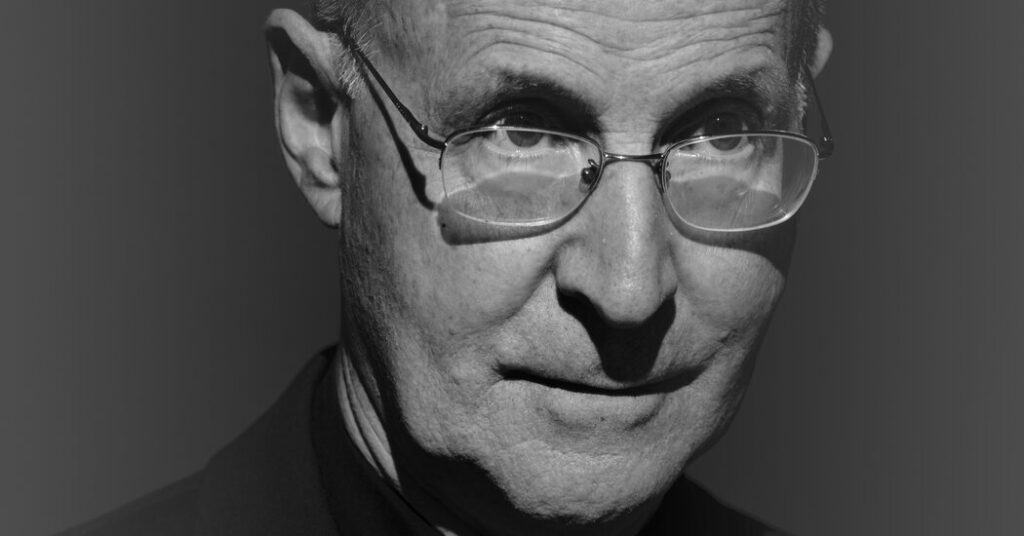

Martin is a Jesuit priest, a best-selling author, an editor at large at America Magazine and also a consultant to the Vatican’s Dicastery for Communication. In layman’s terms, that means part of his job is to help explain the Catholic Church to Americans, which he has done on social media, in his writing, even on the late-night talk shows. He has also ministered to L.G.B.T.Q. Catholics — a controversial part of his work that we get into in the longer audio and video versions of this interview — and is part of the progressive wing of the church.

Martin’s efforts have become more complicated as the conflicts in America have divided the church itself: Over the past year, American bishops and clergy have increasingly spoken out against President Trump’s policies, including on immigration. This at the same time that some of the most visible Catholic figures in America — Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt — are in Trump’s administration.

Martin and I spoke about all of this, including the situation in Minneapolis (though we did so before federal agents killed Alex Pretti on Jan. 24). But we began with something more personal, talking about his new book, “Work in Progress,” which is about his teenage summer jobs and how they prepared him for a life of service.

I was reading something that you recently wrote in America Magazine. You wrote: Despair “takes us away from God in the present. It keeps us focused on all the terrible things that may happen in the future, and that means that we can be blind to all the ways, even if they are small, that God is communicating with us now.” I found that quite a meaningful idea. You make the case that instead of focusing on what is lacking, we should be noticing the ways in which God does show up in small ways all the time. How does God manifest itself in those small ways for you? One of the hallmarks of Jesuit spirituality is finding God in all things. God’s presence is not just confined to within the walls of a church or in reading the Bible. It’s in nature and relationships and work and food and entertainment. The key is just being attentive and aware, really noticing. To take an example: If you’re stressed out and you’re facing a difficult medical diagnosis or financial problem and you pray for peace, maybe it won’t come immediately. But a couple hours later, a friend calls and tells you something that helps you to calm down a little bit? See God in that. That’s what I mean about noticing. And sometimes it takes some attention because we tend to want those fixes immediately. Sometimes God’s a lot more quiet and subtle, tricky.

I’ve had varying experiences with Catholicism. I grew up in a very Catholic household. You’ll be happy to know that I was also expelled from one Catholic institution for a bad attitude. The nuns didn’t like me very much. Wow.

And you were not always called to the church. You grew up a sort of negligent Catholic. Is that fair to say? I usually say “lukewarm Catholic.” We weren’t super religious. I prayed to God to ask for things — let me get an A, let me get a home run at Little League — and then if I didn’t, I was mad at God. I used to think of it as a very transactional thing.

We’re sitting here because you’ve just written a book about your summer jobs when you were growing up. You come from a working-class background and many of your jobs when you were young were manual labor. What did you learn from that? Not to treat people who are on the lower rungs of the economic ladder like dirt. But I also learned the value, as I say in the book, of working hard, showing up, being on time, listening to people, apologizing, but not apologizing reflexively. There are a lot of life lessons. And I’m amazed, because when I was a busboy or a caddy or a dishwasher, I just wanted the money. I was really intent on getting rich.

This is the perfect segue, because you end up going to Wharton business school and then working at G.E. You describe going into corporate America as literally soul-destroying. You went to therapy, you got physically ill from it. You hated what you were doing. Why? The vast majority of people I worked with at G.E. were great — moral and kind. But there were enough jerks to make it really difficult, and the emphasis was on the bottom line. This was the ’80s, the age of the yuppie, and Jack Welch was the C.E.O. of G.E. and would fire people regularly. We used to say: “Up or out.” If you weren’t moving up, they would fire you. I couldn’t see myself emulating some of the people above me, so I thought, I want out, but where am I going to go? One night I came home and turned on the TV and there was a documentary about the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. It was so beautiful and romantic and captivating that I went out and bought his autobiography, “The Seven Storey Mountain,” and devoured it. I thought: This is what I want. Where has this been all my life? It took me a couple years to think about it, and I was going to a psychologist because I was so stressed. And one day he said the question that I think every young person should be asked, which is, “What would you do if you could do anything you wanted to do?” And I said: “Well, that’s easy. I would join the Jesuits.” And he said, “Why don’t you?” And I thought, Yeah, why don’t I? So I went home, I called the Jesuits and said I’m ready to enter. And they were like, Who are you?

You’re now this kind of spiritual emissary to the wider world. And I wanted to talk to you about the church right now. How do you see the state of the Catholic Church in the United States? That’s a big question. I would say healthy, except for the fact that only 30 percent [of Catholics] are going regularly. When I visit parishes, people are happy with their parish and they love being Catholic and they love the pope, especially now that we have an American pope — they love Pope Leo. But there’s some division. I think it reflects the political divisions. Among the ones who are still going to church and are still faithful and still consider themselves Catholic, I think they struggle with certain church teachings. Catholics who are more conservative think that the church should be more conservative. Catholics who are more progressive think the church should be more progressive. But I think the biggest crisis would be people who don’t believe in God anymore. We do see people falling away.

It’s interesting, because while there’s that increasing secularization — people have left the church, not so many people go to church regularly — we’re seeing this growing desire, especially among young people, for connection and for faith. The number of Gen-Z Catholics is actually increasing, right? That’s according to a recent Harvard study. [Other data shows that] young churchgoers seem to participate more deeply in the church than perhaps their older counterparts. They go to confession more. They participate in the sacraments. You minister to young Catholics. What do you think is going on? I see different surveys saying different things. I see surveys saying what you just said, and I see surveys saying, Oh, no, that’s all overblown. But anecdotally, I experience that people in their 20s and even younger are going back to church. Someone described it to me as “post-secular,” which I like — that the secular world is just lacking for them. They want a sense of meaning. They want a sense of mystery. They want community. They want to belong. I think people have a natural desire for God in their lives. I really do. And I think for a lot of younger people, they’re finding the secular world just doesn’t do it. I think the challenge is to invite these people who might be looking primarily for an identity into a deeper relationship with Jesus and with God. That’s the key. So while you might be interested in a particular church because of the community itself, which is where we find God, there also needs to be a connection with Jesus and God. So it can’t just be me and my community. Are you helping the poor? Are you living out what Jesus says, or is it just about going to mass and ticking the boxes? People go to church to get something — to get spiritual nourishment, to get reflections on the Gospels, to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist — which is fine, but it also does need to be about giving. Are you doing the hard work of Christianity?

What do you think having an American pope will do for the American Catholic Church? A lot. First of all, it brings the pope and the Vatican closer to people, and therefore it brings God closer to people. He’s not Jesus, he’s not God — and the Vatican is not perfect. But it brings religion closer to people. To have him speak in English is shocking, and when he comes, it’s going to be huge.

Do you know when he’s coming? No. I’ve heard some rumors, but they’re only rumors. But his first visit to the U.S. is going to be nuts.

He said recently in an interview, and I’m speaking specifically of the United States, that he doesn’t plan to get involved in partisan politics. Do you think he’ll be able to keep to that? Look, his mission is to preach the Gospel. And if the Gospel has political implications, so be it. When he sees migrants and refugees being abused, that’s part of Jesus asking us to welcome the stranger. So he’s going to say something about that. I think what happens is people sometimes impute political motivations to what a pope says that is really just the Gospel. Take care of the poor — if that has political implications, well, that’s tough. That’s what we’re supposed to be talking about.

There was a lot of vocal opposition to Pope Francis’ papacy here in the United States among a certain section of the clergy. Is that a problem that Pope Leo is trying to diffuse? He’s definitely trying to diffuse it, and I think he knows it very well. It was really sad. I would say it was a minority, but they were very vocal, very well funded, very persistent. And I was amazed, because some of the same people who said you could never disagree with the pope under John Paul and Benedict were disagreeing with Francis constantly and calling him an “antipope” and a heretic and an apostate. I think there’s a lot of desire among U.S. Catholics for unity. I don’t think anybody likes it — people on the right or people on the left. So I think that they’re looking to Pope Leo to unify the church.

As we’ve mentioned, immigration is a key issue. It’s a real fundamental part of the way that the church sees its mission. And of course, it’s a signature issue of the Trump administration. In the fall, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a rare collective statement objecting to the harsh treatment of immigrants. Words are one thing, action is another. What actions do you think the church should be taking? The church is already taking action by working with migrants and refugees all over the place. Some of my Jesuit brothers work with migrants on the border. So really, it’s standing with people we’ve always stood with, and it’s advocating for people we’ve always been next to. The U.S. bishops have been great on this. It goes back to the Gospel: Jesus said in Matthew 25, “When you welcome the stranger, you welcome me.” It’s pretty clear. People sometimes ignore it, or they explain it away. They say, Well, we only have to take care of migrants who are doing the following things, or, All the migrants are here illegally, when we know most of the migrants are here legally. But I don’t want to focus on just that, because there are other Catholics who don’t listen to other things — like economic things, or paying people a just wage, or caring for the environment, as Pope Francis asked us to do. A lot of people just exempt themselves. The old expression is “cafeteria Catholic” — you pick some things and leave the others. I think in the United States, we are all, to a certain extent, cafeteria Catholics. But the fundamentals really need to be accepted, and one of the fundamentals is caring for the poor and caring for the stranger. It’s hard for me personally to watch Catholics beat up on migrants and refugees. It’s so clear in the Gospels. And if it’s not clear enough in the Gospels, it should be clear enough from Catholic social teaching. And if it’s not clear from Catholic social teaching, it should be clear from what the popes have said. So it’s really, as we sometimes say, invincible ignorance. It can’t be surmounted.

We’ve seen pretty harsh tactics employed by the Trump administration in U.S. cities. On a personal level, I can hear your distress, but I’m wondering what your thoughts are on that. That no matter who a person is, no one should be treated like this. Even if you’re a prisoner on death row, you shouldn’t be treated like this. Everyone has innate human dignity. And so what horrifies me is the treatment, the cruelty, the meanness. I sometimes think: How can people sleep at night? Treating people like dirt and beating them up and calling them names. By the way, Jesus says in the Gospel, If you call someone a name, you’re going to hell.

How should church leaders then deal with this push-pull? Because you’re talking about trying to bring unity. And yet, of course, there is division in society, there is division among the church leaders, there is division among people who are in the pews. I think it’s pretty clear. One, it’s never demonizing the other person, always giving the other the benefit of the doubt. It’s continuing to preach the Gospel in season and out. So I think it’s possible, and I think a lot of bishops are doing a very good job with immigration.

During the first Trump administration, you were very vocal on social media about things that you disagreed with. Have your views shifted on when and how to speak out? Yeah, I try to focus on the Gospel, and I try not to critique someone by name, and I try not to get too political. We all learn on social media what’s good and what’s bad and what lands with people and what doesn’t. I think I’m on more solid ground by just quoting Jesus. I sometimes sub-tweet something and just write: “I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, Matthew 25.” That in itself should be more persuasive than anything Jim Martin says.

You are part of a wing of the Catholic Church that is more liberal. I’d say progressive, but I’m more traditional than you might think.

I think every priest is more traditional than you might think. I believe in every word in the creed. I’m very devoted to Mary. I love the saints. I go to Mass every day. I go to confession a couple times a month. So I’m pretty traditional. But on some things, I think people see me as more progressive. I think that’s fair.

The energy seems to be on the conservative side of the spectrum in the Catholic Church at the moment here in the United States. That’s where we see a lot of the devotion, people coming in wanting to embrace the church. You’ve been criticized for what some see as pushing a liberal agenda inside the church. Would you accept that as a criticism? I would accept that people do criticize me for that, but no, I’m not pushing an agenda. I just try to preach the Gospel, and people interpret it as pushing some sort of liberal agenda. I’m actually not very political. I don’t really know much about politics. But you’re right, there is a lot of energy around the more traditional side of the church these days in the United States, and we have to be attentive to that and meet people where they are. I don’t know, I hope that answers your question. I guess what I’m struggling with, and I’m not saying you’re doing this, but we sometimes overlay political categories to the church — liberal, conservative, progressive, traditional.

The reason I’m asking about this is that there is a renewed debate about the place of religion in American political and civic life: Bible in schools, God being cited by the White House press office, the vice president being one of the most prominent adherents of the Catholic new right. Is there something beneficial about that, something that can be seen as having a positive impact for the Catholic Church in this country? Sure, I think when people bring their faith sincerely into the public square and into relationships with other people, it’s a good thing, as long as it doesn’t imply that somehow God is on our side completely and if you’re not with us, then you’re against God. That’s the problem: that Jesus is on our side, and if you oppose us, you oppose Jesus. I often wonder why we don’t put the Beatitudes in classrooms. It’s always the Ten Commandments. What about “blessed are the poor,” “blessed are those who mourn,” “blessed are the meek,” “blessed are the peacemakers”? Why is there never a push for the Beatitudes? It’s a very strange thing to me.

Why do you think that is? Because it’s hard, and it’s stuff that we want to avoid. I mean, the Ten Commandments are hard, too. But these days, the Beatitudes are harder.

I think there’s a craving for moral clarity at this moment. As with any conflict, moral clarity is being owned by people with very different viewpoints. It’s like when people were fighting wars in the Middle Ages, and both sides said that God was on their side. How do we understand who is right? I’ve been thinking a lot about Renee Good and her killing. I guess what I come down to is this: Even if you’re breaking the law, no one deserves to be treated like that. So even if you argue that Renee Good was somehow breaking the law, she did not deserve to be shot in the head. And I guess what I’m seeing is this coarsening of morality in the United States, where people think she deserved it. So when you think of people like the inmates on death row, migrants, protesters, L.G.B.T.Q. people, people in Ukraine, people in Gaza — everyone deserves to be treated with dignity. That’s what we’re losing. What’s being set forth is, Only our side deserves to be treated with dignity, and the other side is horrible and evil and subhuman. Which is a disgrace, because for Jesus, there’s no us and them — there’s just us. And all of us deserve to be treated with dignity. I think the church has been very clear about that, and I’m grateful for that. That’s not a political message; that’s the Gospel. Everyone is a beloved child of God, everyone deserves to be treated with dignity — and not shot in the head.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations. Listen to and follow “The Interview” on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, iHeartRadio or Amazon Music.

Director of photography (video): Zackary Canepari

Lulu Garcia-Navarro is a writer and co-host of The Interview, a series focused on interviewing the world’s most fascinating people.

The post Rev. James Martin on Our Moral Duty in Turbulent Times appeared first on New York Times.