It was 2023, homicides in D.C. were spiking to levels not seen in a generation, and the city was spending millions of dollars to deploy violence interrupters to the neighborhoods where shootings were endemic. They were paid to convince people to put down their guns, in some cases succeeding.

But for some working at one nonprofit, Life Deeds, the city’s investment in violence interruption became an extra business opportunity. The executive director and employees used hundreds of thousands of dollars in government grants in ways that a top city official says undermined the anti-violence mission and should never have been allowed, according to a Washington Post investigation.

The D.C. government awarded Life Deeds $3.6 million in violence prevention grants over the course of 15 months from October 2023 through December 2024. The group used more than $411,000 of that money to hire businesses owned by or linked to its own employees or their family members, according to a Post review of thousands of pages of financial records for Life Deeds.

Using taxpayer funds, Life Deeds held events or activities — promoted as opportunities for trust building, community bonding and education — that included lavish dinners, go-karting trips to New Jersey and an alcohol-filled pool party where Life Deeds hired its employees’ companies to provide decorations, refreshments and DJ services, records show.

At the same time, the D.C. government was reimbursing the then executive director of Life Deeds, Allieu Kamara, twice each month for rent on the same building, paying him or his company $60,000 in duplicate payments over one year, according to invoices the group submitted to the city.

The spending was a “completely inappropriate use of public money that should not have happened,” City Administrator Kevin Donahue said after he was briefed by The Post about its review of the group’s financial records, which were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request. Donahue said the city had independently investigated the group’s spending and surfaced similar findings.

“These grants are meant to do some of the most important work, and when it’s effective, lives are saved,” Donahue said. But, he said, Life Deeds spent some of the funds in ways that were “unreasonable, in some cases unethical,” and, in other instances, “possibly illegal.”

The findings spotlight failures by the D.C. government to safeguard taxpayer money: The agency overseeing the program repeatedly approved the nonprofit’s expenses and outsourced monitoring of the spending to a third-party organization.

Several contracting experts and attorneys told The Post that some of the spending by Life Deeds may have violated federal or city laws that prohibit nonprofit executives from financial arrangements that benefit themselves or insiders connected to the nonprofit.

In December 2024, the city severed business ties with Life Deeds after Kamara pleaded guilty to federal fraud and bribery charges involving city contracts unrelated to his group’s violence interruption work. At the time, as The Post previously reported, he was also acting as an FBI informant in a corruption investigation that led to the arrest of D.C. Council member Trayon White Sr. (D-Ward 8) on a bribery charge, to which White has pleaded not guilty. White allegedly agreed to try to steer violence intervention grants to Life Deeds in exchange for $35,000 in cash and over $100,000 in kickbacks from future grant money, according to White’s indictment. White, who is scheduled for trial in March, declined to comment.

Kamara declined to comment or answer questions through an attorney. The Post also contacted or tried to contact 11 former Life Deeds employees, who declined to comment or did not respond. The group’s interim director, who succeeded Kamara after he pleaded guilty, declined to comment.

The D.C. agency overseeing the violence intervention program, the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (ONSE), declined to comment on Life Deeds or make its executive director, Kwelli Sneed, available for an interview.

Donahue said ONSE has tightened guardrails on grantee spending since terminating the city’s work with Life Deeds. The agency no longer employs Progressive Life Center, the nonprofit it had hired to oversee grantees and review their spending. Donahue also said the D.C. government is “urgently” developing technology to prevent contractors or grantees from receiving duplicate reimbursements.

Violence interruption work can be grueling and, at times, dangerous for frontline employees. White’s arrest and Kamara’s role in the bribery case have heaped scrutiny on the work in D.C., leading to calls for more oversight.

“It’s been embarrassing for everyone,” said Delonte Gholston, pastor at Deanwood’s Peace Fellowship Church and founder of the anti-violence nonprofit Peace Walks DC. “That one organization’s misdeeds has been used to characterize the entire movement, that’s unfortunate.”

Beyond the finances, it is difficult to assess the quality of work done by Life Deeds. Members of the D.C. Council have long noted the city’s violence intervention program lacks reliable benchmarks to measure success.

Reviews of Life Deeds work were mixed, with some residents saying the group reliably responded to shootings and others saying it failed to deliver on services it promised the city.

Cynthia Hall, chief operating officer of the Columbia Heights Village Tenants Association, worked with Life Deeds in 2024 after asking the city for help to combat violence in the neighborhood. Bullet holes pocked the playground equipment on the property in Northwest Washington. Gunfire had shattered bedroom windows and all sense of security.

Hall said Life Deeds did not follow through on the tenant association’s suggestions for community programming and left it with questions about how the group spent city funding.

“When we see people don’t take it serious that there should be oversight in where these funds go to help people, it hurts us,” Hall said.

From bribes to grants

There were warning signs years ago about the business practices of Life Deeds.

Kamara founded Life Deeds in 2009, doing business out of a pair of properties east of the Anacostia River that doubled as group homes for some of the city’s most vulnerable residents. A former U.S. Army captain with roots in Prince George’s County, Kamara had some ties to D.C. politics through White but otherwise was not a high-profile figure in the metro area.

From 2012 to 2024, the city awarded Life Deeds over $20 million in contracts and grants from multiple agencies serving homeless people and troubled youths. More than $11 million of that was awarded after the city became aware in 2019 of what one contracting official described in a legal filing as an “egregious” problem with the company’s work.

That year, the D.C. Department of Human Services terminated the Life Deeds contracts after finding the nonprofit falsified criminal background checks for its employees at a city homeless shelter it operated. Kamara unsuccessfully fought the contract terminations in court and also argued the city should cover $338,000 in “wind down” costs and early termination fees for space it had leased at a run-down strip mall. In legal filings, the D.C. attorney general’s office called the lease “suspect” and the claim of a $12,000 monthly rent “incredible,” noting that it far exceeded the rent for similar space in the federal Ronald Reagan Building two blocks from the White House.

The case resulted in a settlement in which Life Deeds admitted no wrongdoing but abandoned its demands for damages, records show.

According to White’s indictment, an informant — later identified as Kamara — told the FBI that he paid White a $20,000 bribe to try to pressure officials to resolve a 2019-2020 contract dispute in Kamara’s favor. The details of the contract dispute matched the city’s termination of DHS contracts with Life Deeds.

The D.C. government considered debarring Life Deeds from city grants and contracts for five years, city officials previously told The Post. It never followed through, and the officials said the case fell through the cracks as the pandemic began.

Meanwhile, Life Deeds continued to get government work.

Some of these contracts and grants, Kamara has since admitted in federal court, were secured illegally. He pleaded guilty in 2024 to paying a contract specialist with the Child and Family Services Agency more than $230,000 in bribes in exchange for help with steering $2 million in contracts to Life Deeds and one of his other companies over nearly five years. He awaits sentencing.

In a separate federal case, Dana McDaniel, a former ONSE deputy director, pleaded guilty to bribery in March, admitting that sometime before September 2022, she told a city contractor that she would help him obtain violence intervention grants in exchange for money. That contractor was Kamara, she later revealed in court — and beginning that September, Kamara’s companies, including Life Deeds and District Services Management, began to receive new violence intervention grants. Kamara, acting as an FBI informant, offered McDaniel $10,000 in a car in August 2024 to make good on the deal, according to plea documents. McDaniel accepted — though said in court that she took no action to help Kamara secure grants.

On Sept. 23, McDaniel was sentenced to 46 months of probation, including 16 weekends in jail.

At McDaniel’s sentencing hearing, she apologized to the violence interrupters and to D.C. residents: “My personal apologies for failing them in my moment of fear and panic.”

One shooting leads to another

Violence interruption programs are built on the idea that one shooting often begets another, and that trusted neighborhood leaders — many of them formerly imprisoned — can convince shooters to halt cycles of retaliatory violence.

The violence in D.C. often starts with interpersonal conflicts between “crews” or neighborhood cliques, leading to retaliation, said Dwayne Falwell, founder of Together We Rise, which D.C. has hired to do violence intervention work.

“It’s a really small group of people that’s actually the shooters or the guys that commit these heinous crimes,” he said. “And so the thing is — get to them, get the resources for them and find out” why they are driven to shooting.

D.C.’s grants to Life Deeds — and four other groups — required its employees to cultivate relationships with young adults who were at the highest risk of committing gun violence and become a “known presence” in the neighborhoods.

They were to respond to shootings and visit victims in the hospital and shooters in jail. They were to document their efforts through daily meetings with ONSE and weekly and monthly reports, the grant agreements stipulated.

Life Deeds employed about 20 staff members and paid most of its frontline violence interrupters $3,000 to $4,000 a month after taxes, according to six months of payroll records for the group. The Post did not obtain full payroll records for Kamara, but in October 2023 and March 2024, he was paid $9,000 on a semimonthly basis after taxes, suggesting monthly earnings of over $18,000, records show.

Daily reports that Life Deeds violence interrupters submitted to ONSE show that they mediated conflicts between rival crews, checked school attendance, prepped young adults for job interviews, comforted grieving parents and even aided in funeral preparations.

“Received a call from a concerned parent in the 16 Street neighborhood fearing that her son may be in danger,” violence interrupter Stephen X wrote on May 31, 2024. When he arrived, three people were shot, and one was dead. He took two distraught bystanders to a safe space. “When the timing was right, [I] broke the news to the 2 residents that their friend did not survive.”

Residents’ experiences with Life Deeds varied by neighborhood.

Tiffany Dailey, a former resident council president in the LeDroit Park neighborhood, said one violence interrupter in particular had a knack for reaching the highest-risk young men, showing up at community events with food or taking them on trips. But she said the approach by Life Deeds felt a bit “ad hoc” and needed more consistency to help young men get jobs.

“I appreciated what they did offer,” she said, “even if it wasn’t as much as I would like.”

Carlo Perri, an advisory neighborhood commissioner in Columbia Heights, said he met various Life Deeds violence interrupters last year and believed they “genuinely meant well, and on a person-to-person level did have a positive impact.” But residents had serious concerns about how money was being spent.

“Unfortunately,” he added, “at a systemic level, it was an abysmal failure.”

Life Deeds had broad discretion when spending the more than $3 million it received from ONSE annually. The flexibility allowed it to avoid onerous paperwork and to determine which types of community events, workshops and field trips were best for connecting with hard-to-reach individuals.

Those events also generated additional income for salaried Life Deeds employees.

‘Miami Nights’ and day trips to New Jersey

In March 2024, Life Deeds planned several Easter-themed events, including one at Columbia Heights Village, where Hall had been asking for help to turn the tables on gun violence.

She remembered the afternoon event featured hot dogs, face painting, a DJ and a person dressed as the Easter Bunny. Hall said children danced and ate candy.

But the $6,000 in invoices that Life Deeds submitted after the event to the D.C. government report that much more had been provided: a moon bounce, a snow cone machine, a cotton candy machine, a popcorn machine, a 360-degree camera, barbecue chicken, string beans and rice.

Hall recalled none of those items.

“It was cute for the kids,” Hall said. “It just wasn’t honest.”

The Easter event underscores a pattern in Life Deeds billing: Every invoice for the event expenses submitted to the city by Life Deeds for payment — such as the procurement of a moon bounce, the $2,500 billed for catering, and the DJ — came from one of four companies linked to salaried Life Deeds employee Cameron Williams.

The records disclosed to The Post include no underlying receipts showing how much was spent on the various items.

Overall, the companies owned by or linked to Williams were reimbursed nearly $120,000 over 15 months for services they reported providing at Life Deeds events or activities. Williams is listed as the owner of one of the companies, MediaSalon LLC, in D.C. business registration records. Two of the other businesses — DC Food and Beverage and DC Events and Gaming — submitted invoices that sometimes listed his name. Those three businesses and a fourth — Universal Barbering and Styling — were all reimbursed for the event through two bank accounts identified as “mediasalon” and “mediasalonman,’’ records show.

Contacted by The Post, Williams declined to answer questions.

In June 2024, Life Deeds reported hosting a “Miami Nights” Father’s Day pool party at a house in Bowie. A flier posted on Instagram promised the bar would be free and frozé — frozen rosé — would be served. Guests would enjoy food and a DJ, too. “FREE ENTRY FREE EVERYTHING,” the flier said.

Life Deeds hired four businesses linked to its salaried employees — including Williams’s DC Events and Gaming — to provide decorations, food and drinks, and DJ services, paying a total of nearly $8,000, records show. The other three companies were registered to the employees or linked to an employee through payment data, records show. The employees declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.

Life Deeds told the D.C. government that the Bowie event would include workshops on nonviolence and a panel discussion on positive male role models. Video of the party posted by a Life Deeds employee on Instagram showed flowing booze and women dancing in bikinis.

On at least three occasions, Life Deeds was reimbursed by taxpayers for lavish dinners, including a nearly $1,100 meal in February 2024 at Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse in downtown D.C. for a group of 10.

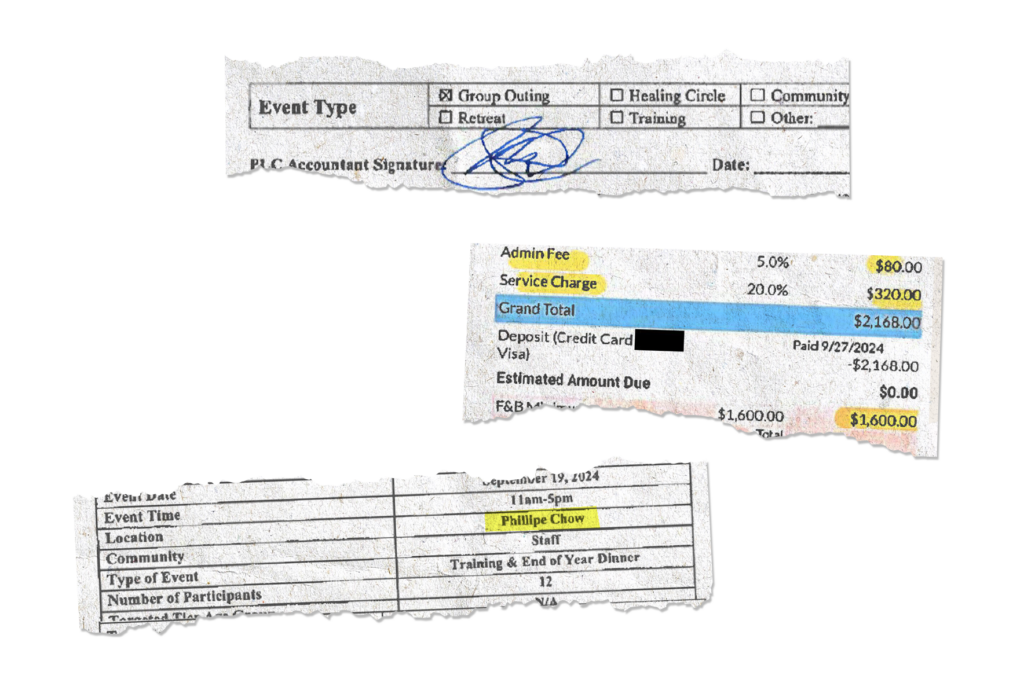

In September 2024, about six weeks after Kamara pleaded guilty to fraud and bribery, a Visa card issued in his name was used to treat the Life Deeds staff members to a $2,000 “Training & End of Year Dinner” at white-tablecloth Philippe Chow at the Wharf. As part of the event, Life Deeds also paid two of its employees $1,000 combined to provide a violence interruption training session to other employees, records show, though D.C. offers free mandatory training for violence interrupters. The D.C. government reimbursed Life Deeds for all of these expenses.

For transportation to many of these activities, Life Deeds reported hiring four companies owned by employees or their family members, paying them a total of nearly $54,000 over 15 months, city records show. Some activities were roughly 200 miles from D.C., including trips to New Jersey to go go-karting or to a mall with a theme park.

Before D.C. signed off on reimbursements, a local nonprofit and ONSE grantee called Progressive Life Center was tasked with making sure the expenditures were appropriate.

In the records provided, Progressive Life Center denied reimbursement only once to Life Deeds — a request for $5,300 to take eight young people to an NFL game in Philadelphia. A 2024 review by the D.C. government — initiated after White’s arrest — found that Progressive Life Center repeatedly signed off on inappropriate spending by violence intervention grantees, though it did not offer specific examples of improper spending. Officials with Progressive Life Center did not respond to requests for comment.

According to internal emails obtained through a FOIA request, one compliance employee at ONSE raised concerns to superiors about potential violations of the grant agreement, including failing to maintain enough community partnerships, working with youths who were not high risk, and some expenses that appeared dubious. It is unclear how or whether superiors responded to concerns.

Donahue said it’s appropriate to spend money to “do activities that try to build trust with young people,” including field trips that “get them out of harm’s way.” Many in the violence interruption community see the trips as essential to build a rapport and offer them experiences outside the streets of D.C.

But there is a line, Donahue said.

“It is a completely inappropriate overreach to then take those basic functions that can be essential to building trust and extending them to the point where you’re having lavish dinners, there’s alcohol involved,” he said. “You’re doing things that, quite frankly, undercut the very work that we fought so hard to be able to fund and have people believe in.”

Roger Bell was the program manager for Life Deeds who oversaw its citywide violence intervention grant and later served as interim director. A company co-owned by his wife, Discerning Dreams, received roughly $55,000 from Life Deeds to host workforce development workshops in Wards 7 and 8, records show; Bell declined to answer questions about Life Deeds or the arrangement.

In an interview, Bell’s wife, Leslie Bell, said she was never told that her company’s dealings with Life Deeds posed any issues, and she did not know if her relationship to Roger Bell was ever disclosed. She said it was Kamara, not her husband, who was in charge of the final approval of vendors and expenses.

The downfall of Life Deeds saddened her, she said, because she saw real impact. Her company helped people put together résumés to prepare for job interviews and hosted conflict resolution workshops.

“I’m sure Life Deeds will be sorely missed — not the company, but the actual work that was being done in the community,” she said.

Double-dipping from taxpayers

Kamara operated Life Deeds out of a four-bedroom home with a red-brick facade in Marshall Heights that he purchased in 2009.

Over the course of a year, Life Deeds billed taxpayers for monthly rent on this same property to two different grants — a pattern of duplicate billing that city officials acknowledged they did not catch.

Every month, Life Deeds charged the Child and Family Services Agency $5,000 for rent of the “entire dwelling,” where Life Deeds operated a group home. The rent was paid to the landlord, Kamara, according to the lease submitted to D.C. government.

Yet every month, Life Deeds also billed the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services $5,000 for rent for the “entire dwelling,” according to a copy of that lease. The landlord was District Services Management, a company owned by Kamara, according to business registration records.

The end result, for Kamara, was that the city paid him or his company $60,000 in duplicate payments over a year. The monthly total of $10,000 in rent was far beyond average rents for the area at that time, according to Zillow, and more than five times the cost of Kamara’s monthly mortgage.

Spokespeople for both agencies declined to comment, citing unspecified “ongoing litigation.”

Donahue described the duplicate rent payments as a “breakdown” in the government’s systems for monitoring the spending of grantees at different agencies. He said the new system his office is developing will catch duplicate expenses submitted by contractors and grantees.

Nonprofit executives are prohibited from using the nonprofit to benefit themselves or insiders connected to the nonprofit under both federal and D.C. law, said David Colapinto, an attorney who specializes in government contract fraud and represents whistleblowers. The D.C. government, he said, should have had a sharper eye for those potential violations. “It’s taxpayer money, and ultimately the government agencies and the city council have a duty to the taxpayers to ensure that it isn’t wasted and that there isn’t fraud and abuse in these contracts and grants,” Colapinto said.

He and other attorneys said potential conflicts of interest are not always a problem with the Internal Revenue Service — as long as they are properly disclosed to the nonprofit’s board and reviewed thoroughly.

According to annual disclosures from Life Deeds to the IRS, the nonprofit reported having a policy to protect against conflicts of interest, offering the same typo-filled explanation year after year: “POLICY IS REVIEW AND BOARD MEMEBRS ARE REQUIRESD TO SIGN.”

The Post attempted to contact the Life Deeds board members listed on its federal tax filings to ask about any steps taken to ensure the financial arrangements met IRS guidelines.

Two of them — including a man who told The Post he was Allieu Kamara’s estranged stepbrother — said they were listed on the 2016 to 2023 federal IRS forms without their knowledge or consent. They said they had never attended or been invited to a board meeting, and one demanded her name be removed from the document. The third board member listed did not respond to a phone call and email seeking comment.

In the most recent filing for 2024, the board members were replaced with two new individuals — both with the last name Kamara — neither of whom could be located for comment.

‘It cannot be a free-for-all’

More than a year later, the downfall of Life Deeds and White’s arrest continue to cast a shadow over the violence intervention program as a whole.

Skepticism about the program reached the U.S. Capitol in September. During a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on crime in Democrat-run cities, the D.C. Police Union chairman raised White’s bribery arrest and told senators that “violence interruption in the District of Columbia is a grift, and it is a way for tax dollars to get funneled into the hands of criminals.”

That perception has required violence interrupters to work hard to rebuild community trust, said Falwell, who runs the violence intervention group Together We Rise.

“I mean, you look at Capitol Hill, the White House — all they talk about is the negative things,” Falwell said. “They don’t talk about the good things we’ve done.”

Council member Brooke Pinto (D-Ward 2), chair of the Public Safety Committee, which oversees the city’s violence intervention programs, secured a written promise over the summer from officials in Mayor Muriel E. Bowser’s administration, including Donahue, to hold ONSE to higher standards and require ONSE to use evidence-based strategies.

“It cannot be a free-for-all,” Pinto said.

Her concerns were informed in part by feedback from University of Maryland professor Joseph Richardson and his research partner, Daniel Webster, who have been evaluating D.C.’s violence intervention programs for a forthcoming study. Webster, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, has testified that ONSE did not employ enough violence interrupters and did not use strategies backed by sufficient research.

“Thus far, I will be very clear and frank that we’re not seeing beneficial effects” from violence interruption programs in D.C., he said at a D.C. Council hearing in October 2024.

Lindsey Appiah, D.C.’s deputy mayor for public safety and justice, told Pinto in a hearing this month that the agency has made significant progress on finalizing the new evidence-based model.

New requirements are also forcing stronger oversight, Falwell said. Money isn’t spent without ONSE’s advance approval, he said. Agency employees show up at events to ensure that what the organization billed for is actually present, he said, and three quotes are required before hiring vendors.

ONSE has also tightened its policies on trips, limiting them within a 100-mile radius of the city and requiring advanced review before any travel spending occurs, city officials said.

Hall said despite her experience with Life Deeds, she still believes in the violence interrupters — as long as the D.C. government manages the program with care.

“That is something that also has kept us fiercely fighting for the government to get it right. Because we know that there is a need.”

This spring, the bullet-riddled playground in Columbia Heights was dismantled.

The post How D.C. allowed ‘completely inappropriate’ spending by anti-violence group appeared first on Washington Post.