A wedding gown from a failed marriage sits in a cardboard box at a mall in Vancouver. Nearby, there’s a can of spilled paint, rejection letters and a poster of a missing cat.

The objects are part of “The Museum of Personal Failure” — a collection of submissions representing things in people’s lives that didn’t work out.

“When I first started it, there wasn’t a plan,” said Eyvan Collins, 34, who created the museum. “I didn’t have a vision for what it would become.”

After back-to-back relationship breakups last summer, Collins was feeling defeated.

“It just felt like I had failed both of these people, and I was sad,” Collins said. “I was processing these losses.”

Collins, who works as a truck driver and creates art projects on the side as a hobby, wanted to connect with others who had experienced failure.

“At the beginning, maybe selfishly, I was trying to process my own feelings and feel less alone,” said Collins, who put “FAILURES WANTED” posters around the city and on Facebook in August. “I love interacting. I love strangers.”

“The Museum of Personal Failure is seeking submissions of artifacts — rejection letters, attempted repairs, abandoned art projects, ruined experiments — all manner of failure artifacts are welcome,” the poster read, along with an email address for submissions.

“I didn’t know how people would react,” Collins said. “It was sort of a ‘see what happens’ thing.”

Submissions poured in over several months, and Collins realized there was enough material to bring the idea to life. Inspired by the Museum of Broken Relationships in Croatia, and “The Museum of Failure” — a global exhibit that showcases failed business ideas and products — Collins wanted to try something similar but on a smaller, more personal scale.

Collins rented a space at Kingsgate Mall and selected about 40 of the nearly 100 submissions for display. Most artifacts are accompanied by brief descriptions written by the people who submitted them. Some opted to stay anonymous, while others signed their names.

“Some people wrote a story about what happened or a poem, and some people didn’t want to say anything at all,” Collins said.

The exhibit opened on Jan. 24 and will close Feb. 4, with free admission. There has been a steady stream of visitors, especially since the show was covered by the CBC in Canada.

“It’s been pretty nonstop,” Collins said, adding that contributors set up their own displays. “The first few days, we had like 500 to 600 people a day.”

The response, Collins said, has been overwhelmingly positive, and visitors have found the project deeply relatable.

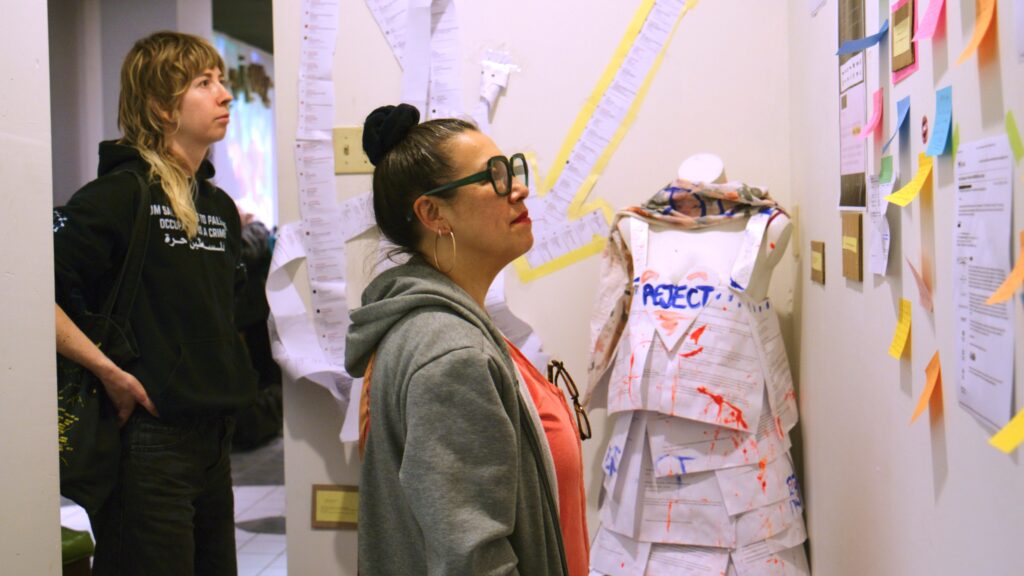

Among the artifacts is a dress composed of rejection letters, created by Shawna Ariel, who saw Collins’s posters seeking participants.

“I kept seeing them everywhere,” said Ariel, 28, an art student. “I’ve failed so many times.”

She combined all the rejection letters she’s received in her life — jobs at coffee shops, art galleries, art residencies and exhibitions to which she wasn’t accepted — and fashioned them into a dress. There are about 50 rejection letters, and Ariel painted the word “reject” on a heart at the top of the dress.

“The way the museum has worked is transforming something that people were maybe initially ashamed of or embarrassed by into something they can proudly show,” Ariel said. “It takes a lot of courage to show this kind of stuff.”

Ariel said she is appreciative of her failures, as she’s learned something from each one, and they’ve given her more drive.

“Failure has made me who I am,” she said.

Charlie Materi’s rusty scissors are also on display, representing Materi’s “failed” career as a barber.

“I never got to the point where I was confident enough, and, eventually, I just gave up,” said Materi, 40, who trained as a barber in 2021 and quit about a year later. “Every time I did it, I would struggle with so much anxiety, and I felt like there were some gaps in my training, and I didn’t have anyone to help me.”

Submitting the scissors helped Materi rethink quitting barbering. In fact, Materi recently returned to cutting hair.

“Seeing everybody’s artifacts together was just so moving,” Materi said. “It’s such a lovely, beautiful thing, and I think it was really healing for a lot of people, including myself.”

Zafreen Jaffer, 32, took a painting class in April, and made a piece she wasn’t pleased with. She decided to display it in the museum.

“Exhibitions like this are really important, because you are teaching people that it’s okay to fail at something,” Jaffer said. “Failures are not full-stop; they are more a journey to somewhere. … You tried something, and that in and of itself should be celebrated.”

Many visitors have complimented her painting, which depicts bunnies on a playground. She now sees it in a different light.

“It may not always work out the way you want it to, but the result is still meaningful,” she said. “There is still something to be gained.”

Rheanna Toy, a filmmaker, heard about the exhibit on Facebook and is working on a documentary about it.

“I was drawn to not just the quirky exterior of this project but the depth and humanity of the people involved,” she said. “There is so much insight and wisdom behind each item that is in the museum.”

Toy said turning failures into works of art has made contributors proud of their past, and visitors are comforted to see they’re not alone in their struggles.

“It’s like flipping the script, because normally you want to hide your failures away,” she said. “It’s a magical thing Eyvan has created, where people are able to look at these items which represent a period of time in their life differently.”

Collins said the show is an opportunity to reframe painful experiences and challenge “the narratives we cling to.” Collins wants the word “failure” to feel less absolute.

“One guy came up to me and was like, ‘Some of these things, I don’t feel like they’re failures,’” Collins said. “It makes me wonder what failure is.”

After all, “it’s a room full of things that people tried and put a lot of time and care into,” Collins added. “It’s very human.”

The post At the ‘Museum of Personal Failure,’ people share their defeats appeared first on Washington Post.