Founded in 1926 as a one-week observance by the historian Carter G. Woodson, the annual celebration of Black history has greatly morphed over the decades, becoming a monthlong occasion in 1976. It has also changed names, from Negro History Week to African American History Month to Black History Month. Each alteration reflects the developing presentation of Blackness, while the latter intimates a broader acknowledgment of the African diaspora. Likewise, Black cinema has expanded. The films in this collection chronologically present the emergence of groundbreaking Black directors, expansive female and queer-centered stories, and their wrestling with Black representation.

‘The Flying Ace’ (1926)

Stream it on Criterion Channel.

By the 1920s, “race films,” movies starring largely Black casts, marketed to Black audiences and often produced by white-owned companies, were arising outside of Hollywood. Among these companies was Richard E. Norman’s Jacksonville, Fla.-based Norman Studios, which produced “The Flying Ace.”

A six-reel feature inspired by the early aviator Bessie Coleman (she died in an aerial accident the year of the film’s release), “The Flying Ace” is about Capt. Billy Stokes (Laurence Criner), a World War I veteran flier investigating a payroll robbery. His primary suspect is the station master (George Colvin), whose daughter (Kathryn Boyd) is being stalked by the fellow pilot Finley (Harold Platts). Like many race films, the movie is overflowing with action, romance, comedy and crime. Its most elaborate scene is an aerial dogfight between Stokes and Finley, with camera tricks that are the definition of movie magic.

‘Murder in Harlem’ (1935)

Between finding investors and navigating a complex exhibition system, Black filmmakers needed to be resourceful. Few were as inventive as Oscar Micheaux. The director who began his career as a novelist, wrote “The Homesteader” (1918), a book he shopped to the Black-owned Lincoln Motion Picture Company, before adapting, producing and directing the film under his newly founded Micheaux Film and Book Company.

Micheaux’s 34th film, “Murder in Harlem,” was a remake of his earlier silent picture “The Gunsaulus Mystery” (1921). In the new version, Henry Glory (Clarence Brooks), a Black novelist-turned-detective, is hired by Claudia Vance (Dorothy Van Engle) to save her brother, who’s accused of killing a white woman. Partially inspired by the 1913 Leo Frank trial — Frank was a Jewish man lynched for a similar crime — the film is a politically charged whodunit whose depiction of middle-class Black life presents Black people’s growing spending power in the north.

‘The Blood of Jesus’ (1941)

Stream it on Tubi and on the Criterion Channel.

Early in the 20th century, many Black actors transitioned from the vaudeville stage into movies. Spencer Williams was among them. A comedian who gained nationwide fame on television as Andy on “The Amos ‘n’ Andy Show,” he also built an extensive directorial career. His masterpiece, “The Blood of Jesus,” considered lost until the mid-1980s, is indicative of his filmmaking interest in Black religiosity.

In this fantasy film, a Baptist woman (Cathryn Caviness), who’s accidentally shot by her husband (Williams), falls into a coma and imagines herself at a spiritual crossroads. There the devil vies for her soul. To depict her journey, Williams juxtaposes ethereal visions of the heavenly gates with grounded depictions of a jazz nightclub. He also enlists the warm voices of Reverend R.L. Robinson’s Heavenly Choir to provide soothing hymns like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which rapturously grant a rare depiction of rural Black life.

‘Cry, the Beloved Country’ (1951)

Rent or buy on most major platforms.

Based on Alan Paton’s same-titled novel, Zoltan Korda’s “Cry, the Beloved Country” stars Canada Lee as Stephen Kumalo, a small-town South African preacher searching for his family in Johannesburg. There he learns his sister is a sex worker and his son has been charged with killing a white man. With the help of Reverend Msimangu (Sidney Poitier), Kumalo interrogates his own religious views and the cruelties of apartheid.

Lee and Poitier knew each other before Korda’s film. Both were part of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts, along with Paul Robeson; their membership led to their blacklisting. Lee and Poitier were also representatives of two separate generations of civil rights advocates. Consequently, this film’s insistence that turning the other cheek can foster an integrationist society anticipates the movement’s advancement toward Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent teachings. While Poitier would eventually become Hollywood’s major Black movie star, Lee died in 1952 at the age of 45, just as Black actors were beginning to find sizable opportunities in Hollywood.

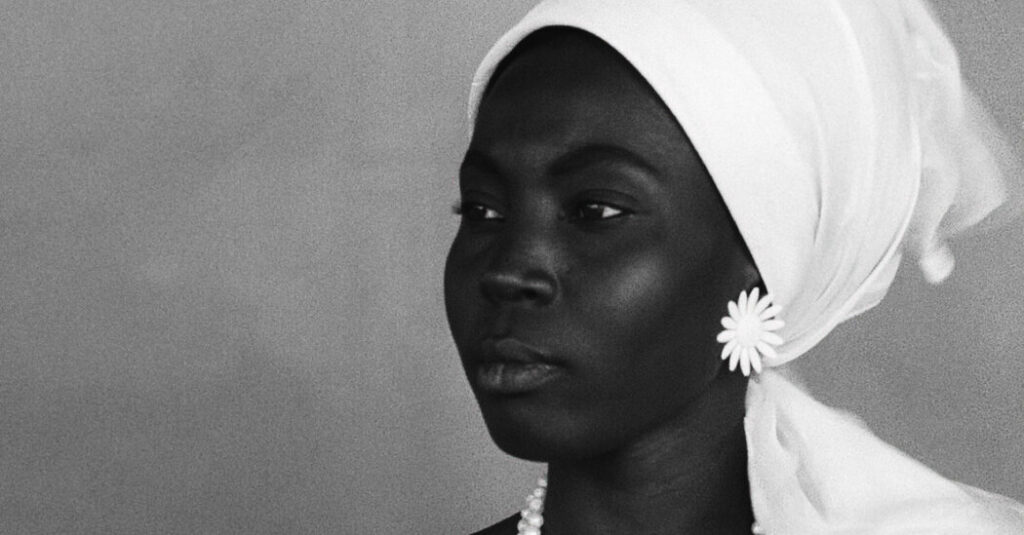

‘Black Girl’ (1966)

Stream it on Criterion Channel.

Racism wasn’t solely restricted to the United States or South Africa. As the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène’s “Black Girl” illustrates, it also persisted in Europe. The film’s protagonist, Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), leaves her impoverished life in her native Senegal only to find menial work and prejudice in France. There she’s a slavish nanny for her French employers and is sexually fetishized at a party thrown by her bosses. These indignities inspire the film’s traumatic ending, where Diouana reclaims her body and her labor.

Like Micheaux, Sembène was a novelist before he became a filmmaker. He switched to directing because he believed film could be a sharp political tool. Sembène found inspiration for “Black Girl,” his debut feature, upon reading about the death of a Black woman in the newspaper. The film, which became one of the first sub-Saharan African films to gain international viewership, energized his career. He is now regarded by many as the father of African cinema.

‘Killer of Sheep’ (1978)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel.

A dramatic shift for Black American cinema, Charles Burnett’s “Killer of Sheep” moved Black storytelling from the heightened stylization of blaxploitation toward the austere neorealist narratives favored by the L.A. Rebellion. The film was Burnett’s master’s thesis at the University of California, Los Angeles, and was shot in the aftermath of the Watts rebellion to tell the story of a Black family shouldering the weight of systemic racism.

Owing to its soul and jazz soundtrack, the music rights delayed the film’s general release until 2007, when Milestone Films cleared them. Since then, “Killer of Sheep” has become a visual and narrative touchstone for independent Black films, like RaMell Ross’s conception of Black boyhood in “Nickel Boys” and Ava DuVernay’s “Middle of Nowhere” — which recalls Henry G. Sanders and Kaycee Moore’s slow dance to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” In Burnett’s film, Black life has never been more tangible.

‘Losing Ground’ (1982)

Stream it on Criterion Channel.

While Zora Neale Hurston and Eloyce King Patrick Gist directed silent shorts, it took until Jessie Maples’s “Will” and Kathleen Collins’s “Losing Ground” for Black women to find the financial backing for making features. Maples and Collins’ films also emphasize sexually adventurous Black women, while “Losing Ground” specifically centers a female protagonist.

In “Losing Ground,” Sara (Seret Scott) is a philosophy professor whose husband, Victor (Bill Gunn), a painter, values his art more than her academic work. When Victor begins fooling around with another woman, Sara leaves to star in a student film and eventually falls for her scene partner Duke (Duane Jones).

Like “Killer of Sheep,” “Losing Ground” didn’t have a wide theatrical release. It languished in obscurity until it was restored by Collins’s daughter in 2015, nearly three decades after the filmmaker’s death. Collins never made another film after “Losing Ground.”

‘Daughters of the Dust’ (1991)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel.

If Jessie Maples and Kathleen Collins cracked the door open for Black women directors, then Julie Dash’s mystical feature debut “Daughters of the Dust” blew the hinges off. Set on a single day in 1902, Dash’s picture takes place among three generations of Gullah women living on Saint Helena Island, South Carolina. Narrated from the perspective of an unborn child, the dialogue is in Gullah Creole and is a loving and keen vision of the African Diaspora. Through reflection and sisterhood, the film considers the transference of tradition, religion, language and history in the face of time and displacement.

“Daughters of the Dust” premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 1991, and became the first feature film directed by an African American woman to be widely distributed in the United States. Its hand-dyed indigo and white dresses have inspired works like Beyoncé’s “Lemonade,” while its overall importance has been cited by filmmakers like Dee Rees and Barry Jenkins.

‘Bamboozled’ (2000)

Rent or buy it on most major platforms.

“Bamboozled” might be Spike Lee’s most audacious work. Playing with a concept that combines elements of “A Face in the Crowd” with “The Producers,” the charged satire follows an exhausted Black TV executive, Pierre Delacroix (Damon Wayans), who creates a modern blackface minstrel whose predicted failure he hopes will lead to his firing. To his shock, the program is a hit.

Nevertheless, the film doesn’t denounce its blackface protagonists: Manray (Savion Glover) and Womack (Tommy Davidson). Lee understands that early Black performers who employed blackface were not only offered limited opportunities but also tirelessly pursued their craft through effort and precision. Tragically, the bigger Delacroix’s program becomes, the more he and his performers lose themselves under their burnt cork makeup — becoming victims to the trap of trying to balance artistry with personhood. The film even ends with an aching montage of blackface and racist caricatures that have proliferated film and television.

‘Moonlight’ (2016)

While Barry Jenkins’s “Moonlight” wasn’t the first Black queer film — Shirley Clarke’s “Portrait of Jason,” Marlon Riggs’s “Tongues Untied,” Cheryl Dunye’s “The Watermelon Woman” and Dee Rees’s “Pariah” laid the groundwork — its overwhelming artistic and critical success signaled the emergence of overlooked Black stories.

The coming-of-age film takes place over three different periods in the life of its young protagonist, Chiron, chronicling his estrangement from his troubled mother, the family he builds with a drug dealer, the homophobic bullying he endures from his classmates, and the love he feels for his classmate Kevin.

Fascinatingly, like “The Flying Ace,” “Moonlight” was also shot in Florida. In that way, both films, through their artistic spirit, emotional clarity, visual grace and unique setting, exemplify that Black moviemaking has always flourished outside of Hollywood. Indeed, through their combined differences they epitomize the wide range of Black life as witnessed by Black artists over the last century.

The post 10 Movies to Stream for Black History Month appeared first on New York Times.