The most thrilling of responsive noises that you can hear in a theater isn’t the thunder of a standing ovation. No, the most exciting sound of all is, in fact, no sound at all — a silence so profound that it seems to vibrate. It’s the deep quiet of an entire audience listening to a single performer speak as if everyone’s lives, on and off stage, somehow depended on what is being said.

That kind of silence is rare and often discussed years later by ardent theatergoers as if something mythic had happened then. So it is worth noting that this kind of hush is occurring right now on Broadway, at Studio 54, where Robert Icke’s “Oedipus,” a contemporary retelling of the ancient Greek tragedy by Sophocles, is nearing the end of its limited run.

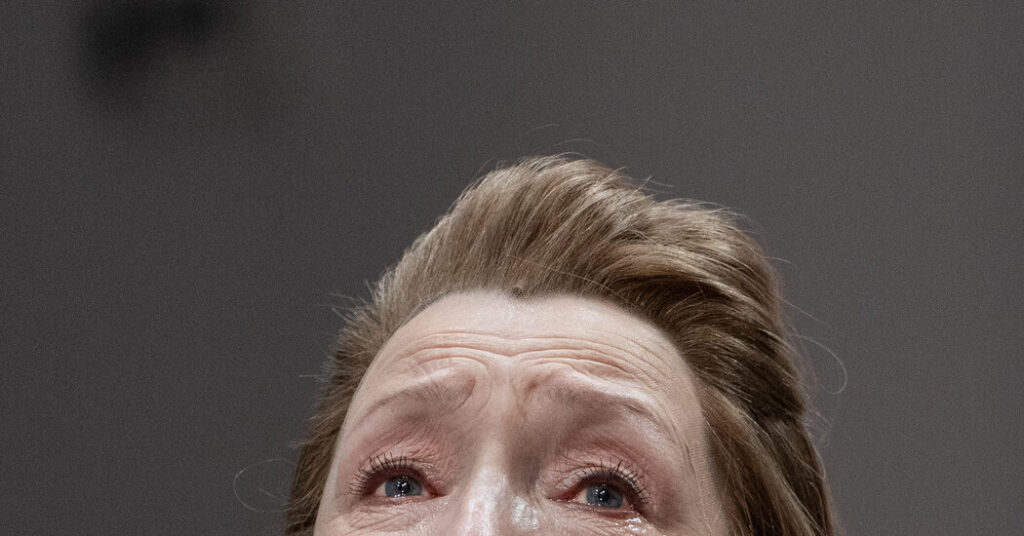

The quiet in this case lasts for a full, taut dozen minutes, though I think anyone who sees it would be hard put to quantify its duration. Never mind that a large digital clock onstage is counting down the moments of an election night for an unspecified, troubled nation. It is safe to say that when Lesley Manville as Jocasta, Oedipus’s wife, seated and virtually immobile in a chair downstage left, is telling a story that her character has never told before, no one is watching the clock.

“Nothing has compared to this,” Manville, 69, a British actress who has starred in New York in such intense classic dramas as Ibsen’s “Ghosts” and O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” said of the energy she feels from the audience during that speech.

The elements that allow this exchange to take place are both simple and mysterious. They include a couple of basic technical elements — “a very gentle lighting change,” according to Icke, and musical underscoring so subtle as to register almost unconsciously — and some staging devices for refocusing an audience’s attention that are as old as theater itself.

Add to that a scene partner, Mark Strong, in the title role, whose own depth of awed, pitying listening — interrupted by an occasional astonished question — inspires and reflects that of the audience; a monologue that finds a character for whom self-control is everything speaking for the first time about a terrifying incident from her childhood over which she had no control at all; and an actress whose own particular combination of paradoxical traits — “calm and chaos,” as Manville put it — matches that of her character. It helps, of course, that she sees the monologue as “one of the greatest speeches ever written.”

An Olivier Award winner for best revival and best actress (for Manville) when it was staged in London, Icke’s “Oedipus” closely follows the existential detective story of Sophocles’ original plot of 2,450 years ago. Once again, Oedipus, a political figure of commanding pride and obduracy, is determined to uncover the truth about his own past. What he finds (spoiler here) is annihilating: Unknowingly, he killed his father years earlier and later married the woman who would turn out to be his own mother.

Much of the audience is probably familiar with a story that is one of the great cornerstones of literature. But it is a testament to Icke’s skill in generating suspense that these revelations still elicit gasps. What theatergoers will not have heard before is the personal history that Icke has written for Jocasta, which emerges by painful degrees in a monologue about three-quarters into the play.

It is an appalling story. At 13, Jocasta, the daughter of a politician, was seduced by the country’s leader, Laius, then in his 50s, and became pregnant. (She would marry him at 17.) The child was delivered secretly, amid harrowing conditions, and taken away from her. This is the tale that Jocasta finally tells, at Oedipus’s unrelenting insistence, after years of doing her best to forget it.

“Why are we all so obsessed with staring backward into the abyss?” Jocasta asks earlier in the play. As Icke said of the character, “She sort of lives in a world where there is no past, because that’s her only option.” Talking about her lost child, fathered by a man she came to regard as unbearably repulsive, she — and we — do indeed seem to have fallen into that very abyss.

“I’m probably going to get tearful now,” Manville said, as she anatomized the contents of that monologue in her dressing room a few hours before a Friday night performance. Dressed in gray and black that echoed the palette of the room, her features both sharp and delicate, Manville registered as equally fragile and formidable.

She said she immediately linked into Jocasta’s impulse to keep sorrows and secrets to herself. “I think I’m too private,” she said. “I remember when my first husband, Gary Oldman” — the film star, to whom Manville was married in the late 1980s — “left me, I didn’t tell my parents for six months. I buried it. And I feel I do that with so much in my life.”

From London, where he is preparing a new production of “Romeo and Juliet” starring Sadie Sink, Icke described Manville in a Zoom interview as “one of the all-time greats.” She is, he said, “somebody who feels very, very deeply and is highly, highly sensitive and protects that very well, because you have to, I think.

“You wear that on the outside and you’d sort of be bleeding the whole time. If all great acting is about embodying contradictions on some level, you feel with Lesley the hardness of the shell and the softness of the inside kind of simultaneously.”

The speech he has given Jocasta here is fitful and full of fragments. “It’s a very disorganized monologue if you look at it,” Icke said. “There’s denial within it. And one of the things I said to Lesley very early on was, ‘Think of it as a scene with five different people, but they’re all you.’”

The monologue was, Manville said, “a complete bugger to learn.” (She always memorizes her lines before rehearsals begin, and said she had already learned most of her role as the marquise in “Les Liaisons Dangereuses,” in which she’ll be starring this spring at the National Theater in London.) But from the moment she first read Jocasta’s speech, she said, she knew “I had to get my hands on it. And I knew that I could go there with it. I knew it would profoundly affect me. And that is what it does every night.”

To make sure the monologue would land with maximum impact Icke placed it immediately after a scene of noisy agitation and confrontation. “It always felt right musically,” he said, “that it would be after a series of sequences where a lot of people talk at the same time — orchestral” with “a lot of dialogue, a lot of raucousness. You were sort of ready for the moment in a piano concerto where the pianist plays.”

In rehearsal, they had staged the scene in a number of ways, with Manville occasionally moving, but concluded that they would keep her almost frozen in that chair, with Oedipus listening intently across the stage. “Your eye as a viewer of theater functions like a camera,” Icke said. “And if there’s movement, you will naturally pull the shot back. Whereas, I remember saying to Lesley, ‘You kind of don’t want to blink in that section’; nothing is moving, you’re drawn towards the person speaking and you’re drawn towards their eyes, and you end up in a close-up.”

The scene, Manville said, is never exactly the same. Jocasta describes herself as being “three things,” in the time she’s describing: “a child myself, the mother of a child, and the lover of a powerful man.” And Manville said she finds she’s never sure, on a given night, which of those will be in the ascendant. But she said she has never performed it when she hasn’t cried. And she agrees with Icke in that “the more still it is, the better it is.”

It is perhaps, above all, that intensely focused stillness that hypnotizes the audience into silence night after night. Icke remembered a conversation he had with Peter Brook, the fabled international theater director, about codifying the different kinds of silence within an audience.

“There’s a silence that is empty with nothing in it,” Icke said. “And there’s a silence where you’re anticipating what someone’s going to do, and you’re like, ‘Oh my God, he’s going to pull a knife.’ And there’s a different kind of silence, of the sort that Lesley can achieve there, which seems to me to have much more to do with a kind of pity, with a sort of awe-struck recognition that this is terrible.”

Manville said she is famous for never missing performances because of illness. But during the Broadway run of “Oedipus,” she has become sick enough on two occasions to be unable to go on.

Icke suggested to her recently that this might be because, on some unacknowledged level, Manville has been taking her work home with her. It’s something she said she had trained herself never to do early in her career during the immersive rehearsal practices of the filmmaker Mike Leigh. But she wondered if Icke might be right in this case.

“The language and the story and the tragedy of the story absolutely wreck me every time,” she said. On the other hand, she added, every night, when that hush descends on the audience: “I am pinching myself, because it was exactly the same in London. And there’s something in the back of my mind that says ‘I don’t know if in my line of work there’s anything better than this.’

“I’m storytelling, and they’re all listening. That is theater in a sentence, isn’t it?”

The post The Devastating Monologue That Is Leaving Audiences Spellbound appeared first on New York Times.