Matthew Rose, an Opinion editorial director, hosted an online conversation with three contributing Opinion writers about the Federal Reserve.

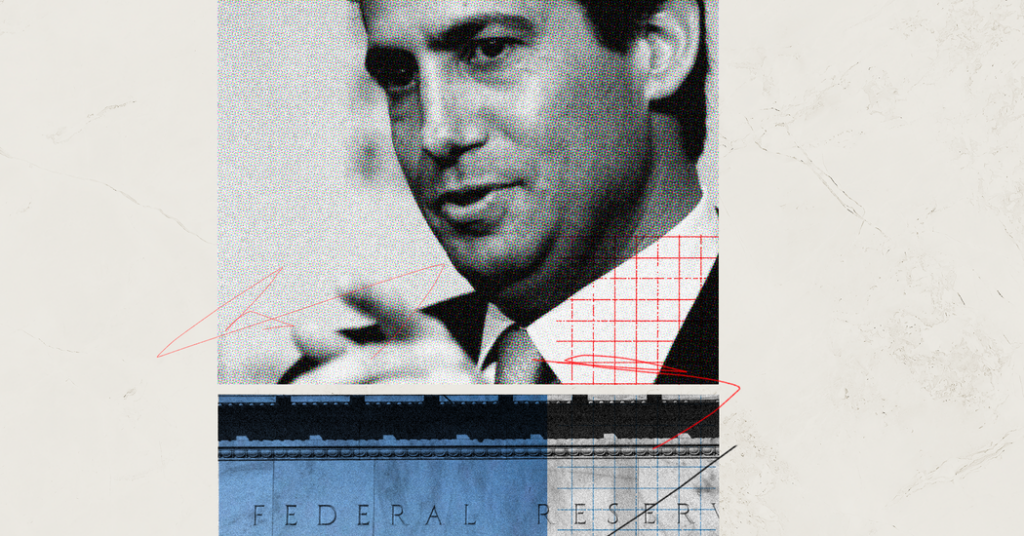

Matthew Rose: After months of trailers and teases, we have President Trump’s nominee to run the Federal Reserve. If you were betting it would be a man called Kevin, congratulations! But instead of Kevin Hassett, the top White House economics adviser and an early front-runner, it’s Kevin Warsh, a former Fed governor who narrowly missed being picked by Mr. Trump in the president’s first term.

Let’s start with your first instincts about the choice. From a scale of 1 to 10, where do you fall?

Jason Furman: Grading on a Trump curve, I would give him a 9. I was relieved by the pick because I believe he is not only very competent, but he is also likely to be his own man at the Fed. In absolute terms, I would be somewhat lower. If you asked me to choose from everyone in the United States, he would not have been my choice. But he is above the bar for the job.

Oren Cass: Well then, put me down for an enthusiastic 8. We appear to be continuing the long-running tradition of qualified Federal Reserve chairs who will strive to maintain independence, subject to the political constraints of our constitutional order.

Natasha Sarin: I guess 6, not using Jason’s Trump curve. If we were, I’d be higher. Warsh has been overly down on the Fed, but on the plus side, he knows the institution and is a believer in central bank independence. We’ll learn more in the confirmation process. More generally, the change of personnel at the top matters less than how the job and the institution will change in the years ahead. It’s a dangerous moment for the Fed and a hard job ahead for the chair.

Rose: So it would be fair to say that you’re not in the same camp as our former colleague Paul Krugman, who called it “a humiliating day for the Federal Reserve.”

Sarin: I disagreed with Krugman saying Warsh isn’t qualified. On paper, this is someone who has been at the Fed as a governor for years and who knows the institution well, and someone who many prominent voices like Jamie Dimon and even Mark Carney, a formal central banker himself, have come out in support of already. But I agree with him that Warsh has shifted from being certain that interest rates should be higher for much of his career to all of a sudden calling for lower rates in November when Trump was re-elected. Given that set of facts, it would be a mistake not to be worried about the potential that this is a chair who could be swayed by the political atmosphere in a way that threatens the central bank’s independence.

Furman: I share Natasha’s nervousness. And think Krugman makes some valid points, but everyone has pros and cons. On balance, if Donald Trump truly believed everything Krugman wrote about Warsh being a hackish political animal who would do his bidding, he would have nominated Warsh for Fed chair a year ago. As was widely reported, Trump thought Warsh had credibility but worried he would show too much independence when he walks into the Eccles Building. And on this judgment, I’m closer to Trump than Krugman.

Cass: Some people were going to complain no matter who Donald Trump nominated, whether it was John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, or anyone in between.

Rose: Can we drill down into what Warsh might bring to the Fed? (He still needs to be confirmed.) Let’s start with the burning issue: Central banks are supposed to be independent because otherwise their decisions are less credible, an idea that has been largely unchallenged in America since the early 1980s. Trump has sharply challenged that premise with his relentless attacks on Jerome Powell, the current chair, whose term is ending. How do you think Warsh will manage that task?

Cass: Central banks are supposed to be independent because many situations will exist where the politically expedient decision is not the one best for the economy’s long-term health. Thus, as with other so-called independent agencies, we have established governing structures that attempt to insulate some policymakers from the direct and immediate pressure of a president’s day-to-day priorities.

We also have a Supreme Court, which is obviously independent from the executive. That doesn’t mean that any of these institutions are above politics or should not be influenced by the values, priorities and ideology of the nation’s elected leaders, both at the moment when members are chosen and in the ongoing give-and-take in which all actors attempt to preserve their prerogatives and credibility. The selection of a new Fed chair is an explicitly set point at which the president is supposed to have influence over the central bank’s direction.

Sarin: Here I am super nervous. Warsh has called for “regime change” at the Fed. I have no idea what that means. He has also said he thinks that while monetary policy independence is important, the Fed isn’t owed deference in bank regulation and supervision. I again don’t know what that means. And I worry it undermines Fed independence meaningfully — you could have a president saying he wants to fire governors not because of their refusal to go along with rate cuts, but because of disagreements about regulation and other policy choices. On the flip side, I’m heartened that he’s said central bankers and political “bandwagons should be strangers.” I couldn’t agree more! I suspect this president doesn’t share my view, though.

Furman: On independence and most everything else about how Warsh handles the job, it is important to remember that, if confirmed, Warsh would be one vote out of 12. If he comes into a rate-setting meeting and argues, “We have to cut rates because Donald Trump wants us to,” he will probably be outvoted 11 to 1. If he wants to be a strong chair who can steer the committee, he will need to protect the Fed’s independence, cut less of a political profile than he has to date and persuade people with ideas and analysis. Absent that, his excellent interpersonal skills won’t get him very far in the boardroom.

Rose: Generally speaking, should Fed chairs discuss policy with the White House?

Furman: Absolutely. I did regularly when I was chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, as do other officials at Treasury and the National Economic Council. I never told the Fed what I thought should happen to interest rates, and they would have ignored me if I had. It is also important to remember the Fed basically has two jobs: One is monetary policy, where they should be independent. The other is regulatory policy, where there is less ideological consensus, less immediate political temptation and thus more reason and less peril for actual coordination with other parts of the executive branch.

Sarin: I think your use of the word “discuss” is important, Matthew. Discuss and not dictate. First, you absolutely cannot have, as you’ve seen many times in the last year, members of the executive branch attempting to influence interest rate policy. I worked for a Treasury secretary who had been Fed chair, and she was the most careful about respecting that monetary policy was no longer her role. Even on regulatory policy, I think the Fed is differentially situated than policymakers elsewhere in the executive branch. The Fed’s regulatory and monetary functions are inextricably linked, and so it’s really important to appreciate that the White House needs to be somewhat at arm’s length.

Rose: Should Powell stay on the board after he steps down as chairman? His term lasts until 2028.

Cass: Traditionally, Fed chairs step down at this point. Insofar as we are successfully going through an entirely normal transition, it would be nice to see it through. “We must adhere to norms, except when violating them keeps my guy around longer” is probably not a good strategy for preserving norms. And as Jason notes, there are 12 members of the Federal Open Market Committee and not a lot of close/split decisions. This isn’t like holding on to a seat on the Supreme Court.

Furman: I hope he does. He is an excellent monetary policymaker, and there is still too much at stake for the institution. Even if the Supreme Court says Lisa Cook can stay in her job for now, it will probably be a ruling on process, not the final word. It is a historical blemish on Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s record that she stayed so long that Trump ended up naming her replacement and thus helped undo much of her good work. (In the case of Powell, of course, it would be choosing to leave that would allow Trump to replace him.) Powell’s place in the history books is as the chair that protected independence. Leaving too early would risk that.

Sarin: Fun fact re: history, Oren. Bob Woodward’s biography of Greenspan was making the rounds the other day. Apparently, had he not been reappointed as Fed chair, he would have stayed on the board.

Rose: Let’s switch to the economic fundamentals. What is the state of the economy Warsh would inherit?

Sarin: Inflation is still higher than the Federal Reserve would like it to be, and the labor market is showing signs of weakening. That makes the Fed’s decision-making at the moment somewhat challenging. Frankly, it’s why you see members of the Federal Open Market Committee on both sides of the “should we cut rates” question. Warsh has traditionally been hawkish, so you would have thought he would be nervous about cutting rates too quickly. He’s shifted from that in the last few months, though, which he has attributed it to the potential for a productivity boom from A.I.

Furman: It’s uncertain, because we’re still suffering from data that was delayed or distorted by the shutdown. My best guess at this point is that it’s pretty good, there is a lot of momentum in G.D.P. growth, the labor market is a bit soft but seems to be stabilizing, and underlying inflation appears to be about 2.5 percent and more likely falling than rising. So it is just possible this could be an easy year for the Fed. But you never know.

Cass: I agree with Jason that we have a lot of uncertainty, around both data and policy, but what we can see looks pretty good. I think it’s especially important to remember that the 150,000 or 200,000 new jobs we became accustomed to seeing each month in a healthy economy assumed a work force expanding with high levels of immigration. With net out-migration, the job growth we have been seeing in the zero-to-50,000 range is what a healthy economy would deliver, which is why we’ve seen the unemployment rate hold fairly steady. It’s hard to think of a lot of times in history when economists would not have been enthusiastic about inflation at 2.5 percent, unemployment below 4.5 percent, and G.D.P. growth above 4 percent.

Rose: Jason, that feels like a change from your assessment earlier in the year, especially around the administration’s big tariff announcement in April. What surprised you in that period?

Furman: Don’t get me wrong, we would be doing even better on growth and inflation without the tariffs. Even while I was using very strong language, which economists can’t help (call it “tariff derangement syndrome” if you want), my numbers were always like half a percentage point off the growth rate. Even in our April discussion, I said the odds were against a recession based on announced tariffs at the time, and the tariffs have since been cut in half. That, plus other countries have barely retaliated. The one shoe that never dropped was uncertainty. We have had record amounts of it, but it doesn’t seem to have actually deterred much business investment. But we’re still all poorer, and everything is less affordable because of the tariffs.

Rose: The reporting on Warsh’s position suggests he thinks we’re replaying some version of the 1990s, where productivity gains, this time from A.I., will allow the bank to lower rates, spur growth and also keep inflation in check. Is he right?

Cass: We have definitely been seeing strong productivity gains in recent months, though it’s hard at this point to attribute it to A.I. But we don’t need the attribution to consider the underlying point, which is that productivity gains are what drive healthy economic growth that can sustain rising wages, low interest rates and modest inflation. A broader push toward re-industrialization, higher levels of domestic investment and tighter labor markets, driven by more restrictive immigration policy, as well as technological breakthroughs, could all help achieve that. It’s certainly good to see policymakers focusing on broad-based productivity growth, rather than G.D.P. growth per se, as the crux of a strong economy.

Furman: I agree that we’re not seeing A.I. in the productivity data yet, but I hope we do eventually. Regardless, the Alan Greenspan story is as much legend as truth. He raised interest rates from 4.75 percent to 6.5 percent in 1999 and 2000. Right now rates are 3.62 percent. If Warsh is able to cut rates a lot, it is much less likely it is because of surprisingly good productivity news than because of surprisingly bad job market news. So Trump should be careful what he wishes for!

Rose: And what about the size of the federal debt? My colleague Binyamin Appelbaum wrote after the Warsh announcement that it will swamp the Fed’s decision-making, like a bowling ball rolling around on an outstretched blanket. The Fed could be pressured to lower rates to lower debt payments. And markets could conclude the U.S. is a bad risk and drive rates higher.

Furman: Interestingly, another person who has raised this worry before is … Warsh. He has argued, not convincingly to my mind, that the Fed has been enabling fiscal profligacy over the past 15 years. That said, it is a risk in the future, and I hope his own past fears and arguments lead him to steer clear of making the mistake himself.

Sarin: You beat me to it, Jason! He says fiscal policy is on a dangerous trajectory — hard to disagree. I, too, am skeptical that’s a story about the Fed and not a story about policymakers in Congress and at the White House. And I am really skeptical of Warsh’s view that we can get to a better fiscal trajectory by rapidly shrinking the size of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. We can debate how many bonds or mortgage-backed securities the Fed should hold, but making rapid changes would be destabilizing to the economy and limit the ability of the Fed to effectively set interest rates and respond to crises down the road.

Cass: We’ve spent decades talking about a fiscal crisis on the horizon, and now we’re actually in one, which I would define as the interest payments on the debt themselves driving deficits and thus debt higher, in a cycle that becomes very difficult to break. To slightly oversimplify, a Federal Reserve that lowers interest rates (i.e., injects more money into the economy) for the purpose of making it easier for the federal government to borrow and spend is essentially doing the money-printing thing. That’s a next step in a fiscal crisis, and a dangerous escalation. It’s also a perfect illustration of the kind of situation for which we do want Fed independence, that Warsh will need to sustain.

Rose: That sounds like the beginning of an argument for cuts to federal spending.

Cass: Yes, and more revenue, too!

Rose: You all just touched on Warsh’s critique of the Fed, so let’s take a closer look. Among other things, he has said the central bank “has acted more as a general-purpose agency of government than a narrow central bank.” By that, he means it has pressured Congress to spend too much and is too focused on climate and race relations and not enough on its core job of managing inflation.

He seems a traditional pick, since he’s a known quantity in Fed World and on Wall Street, but he also sounds like a disrupter. Which one do you think we’ll get? And is there merit to his critique?

Sarin: Listen, I think institutions generally need to be worried about mission creep, so I think it’s totally fair to raise the concern. But I have been dismayed about Warsh’s tone in his criticisms. You’ve heard a lot from him of recent about “dead wood” at the Federal Reserve and “regime change” and “breaking some heads.” You can see how that language is attractive to the president but also makes it pretty challenging to come in and effectively steward an organization.

Cass: Warsh’s critique is shared by many on the right of center. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has likewise condemned what he calls the Fed’s “gain-of-function monetary policy,” and many conversations among policy wonks dive into concern about policies like quantitative easing, the warping effects of zero-interest-rate policy on financial markets, and so on. We also saw Powell get very far out over his skis in the past year, justifying tighter monetary policy in anticipation of tariff-driven inflation that never made sense and never arrived. It’s entirely natural for any institution to steadily expand the scope of its power to the extent it can, but that’s why it’s important to remember that independence has limits and that checks from other institutions and centers of power are important. Hopefully, nominating a Fed chair who sees these problems and wants to address them will be a constructive step.

Sarin: Oren, I don’t really understand the criticism (from you or from Warsh!). Do you think Powell and the Fed more generally were doing anything other than responding to their best understanding of inflation and employment in rate-setting decisions in the past year? We just talked about how uncertain those indicators were. I think Warsh is saying something else, which is about institutional drift as the Fed does climate policy, but a bunch of that is in tension with his view that the Fed should get deference only in monetary policy. So they have a different approach post-January 2025 than they did in the Biden administration. If that’s true, isn’t that what he would have hoped to see? What else would he want to see change? I hope these are questions we see answered in the confirmation process.

Cass: Powell said, “If you just look at the basic data and don’t look at the forecast, you would say that we would’ve continued cutting. The difference, of course, is at this time all forecasters are expecting pretty soon that some significant inflation will show up from tariffs. And we can’t just ignore that.”

We know the Federal Reserve’s own models didn’t necessarily expect tariffs to be inflationary and that one-time price-level changes are not the ambit of monetary policy anyway. Faced with an administration policy that sought to raise some prices through tariffs to spur domestic investment in ways that, if anything, might slow growth and weaken the labor market, an apolitical Federal Reserve would have, if anything, leaned looser. Powell was plainly letting the ideological narrative in opposition to tariffs color his assessment.

Furman: For most of the year inflation was above target and the unemployment rate was about target. Nevertheless, the Fed still cut rates. So what exactly are you so worked up about?

Cass: I’m just quoting how Powell described his own calculus, which was wrong, and indefensible at the time.

Rose: Natasha, you mentioned earlier the Fed’s balance sheet. This is a little technical, but it’s important, so let’s try and work through it. It’s a big strand of Warsh’s critique. The central bank owns more than $6 trillion in assets, including government debt and mortgage-backed securities, which in large part came from financial-crisis era rescues. Do you agree that’s a problem? And if so, how should it be fixed?

Sarin: It is indeed technical, but let’s attempt. One of Warsh’s big critiques of the Fed is that he thinks its balance sheet has grown too large in the aftermath of the financial crisis. I think some of his criticisms have been frankly illogical, like saying low interest rates were to blame for the lack of business investment (it actually goes the other way). Reasonable people can debate the optimal size of the Fed’s balance sheet. But any attempts to make swift changes would damage financial stability. And by the way, if you achieve a smaller balance sheet by dumping mortgage-backed securities, mortgage rates rise.

Furman: Yes, which is ironic because while Warsh has committed to reducing the balance sheet, which presumably would mean selling mortgage bonds, the Trump administration recently announced the opposite with its planned $200 billion purchase of mortgage bonds in an effort to keep mortgage rates low. It will be interesting to see what happens when Warsh’s deep commitment to the idea that the balance sheet should shrink collides with the reality of how financial markets react.

Cass: This illustrates the debates I mentioned above about zero-interest-rate policy and quantitative easing. Trying to address immediate economic challenges through the balance sheet causes inflated asset prices in the short run (which can discourage business investment; why build anything when you can just speculate?) and leaves the Fed with a position that it cannot easily unwind in the long run. This isn’t something you’d want to fix overnight, but a different orientation and weighing of costs and benefits would be helpful. As Jason notes, it certainly argues against buying up $200 billion in mortgage bonds.

Sarin: It’s fine to debate the optimal size of the balance sheet. But I’d discourage throwing the baby out with the bathwater, and I hope that’s not what Warsh (or Oren!) wants to do. Moving away from Q.E. as a monetary policy instrument writ large would be giving up a critical tool that we know is supremely important to effective crisis response for the central bank.

Cass: Agreed entirely regarding a crisis. The issue would be the self-perpetuating logic of Q.E. that seemed to keep it running long after anyone could claim the crisis was afoot.

Rose: Last question. In a speech last year, Warsh said, “We should be unworried about violating pieties, prepared to endure periodic frowns of disapproval.” In a few words, what pieties should he violate? And which should he avoid violating?

Sarin: I hope he’s willing to endure frowns of disapproval from this White House. And I hope the Senate in its advise-and-consent role makes sure that he holds central bank independence as his North Star. That’s the ballgame for the Fed, and it is under more threat today than at any point in the past half-century.

Furman: It’s hard to know exactly what Warsh pieties Warsh actually wants to violate. In general, he does more criticism than explication of his alternative. In some places I agree with him. For example, the Fed should stay out of politics. I just hope he applies that equally to conservative views as to liberal ones. I also agree the Fed has probably relied too much on telegraphing where interest rates are going, often wildly at variance with where they end up. But I have no idea what he will do with his criticism that the Fed relies too much on models and data. What else would he use to set rates?

Cass: I think it has become clear over the past few years that many of the ironclad rules of the Economist’s Code were “more what you’d call guidelines,” to quote Captain Barbossa, and it’s worth questioning those pieties and also keeping an open mind to the policy choices of our political institutions, beyond merely maximizing G.D.P. growth each quarter. On the other hand, the Federal Reserve setting interest rates independent of whatever the White House might tweet is a piety we seem to have maintained well and will hopefully continue to observe.

Oren Cass is the chief economist at American Compass, a conservative economic think tank, and writes the newsletter Understanding America. Jason Furman is a professor of the practice of economic policy at Harvard and was chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers from 2013 to 2017. Natasha Sarin is a professor of law at Yale and the president and a founder of the Yale Budget Lab and was a deputy assistant Treasury secretary for economic policy in the Biden administration and counselor to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. All three are contributing Opinion writers.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post ‘Relieved,’ ‘Enthusiastic,’ ‘Nervous’: Three Economists React to Trump’s Fed Pick appeared first on New York Times.