The Baghdad Battery. You may have heard the words before and had no idea what they meant, but I assure you that string of nonsense actually has some big significance to archaeologists and has been sparking debate for nearly 100 years.

If you need a refresher, the Baghdad Battery was a shattered clay jar found in Iraq in the 1930s that was either just another ritualistic container of no historical significance or maybe it was an ancient battery that provided evidence of early electrical engineering.

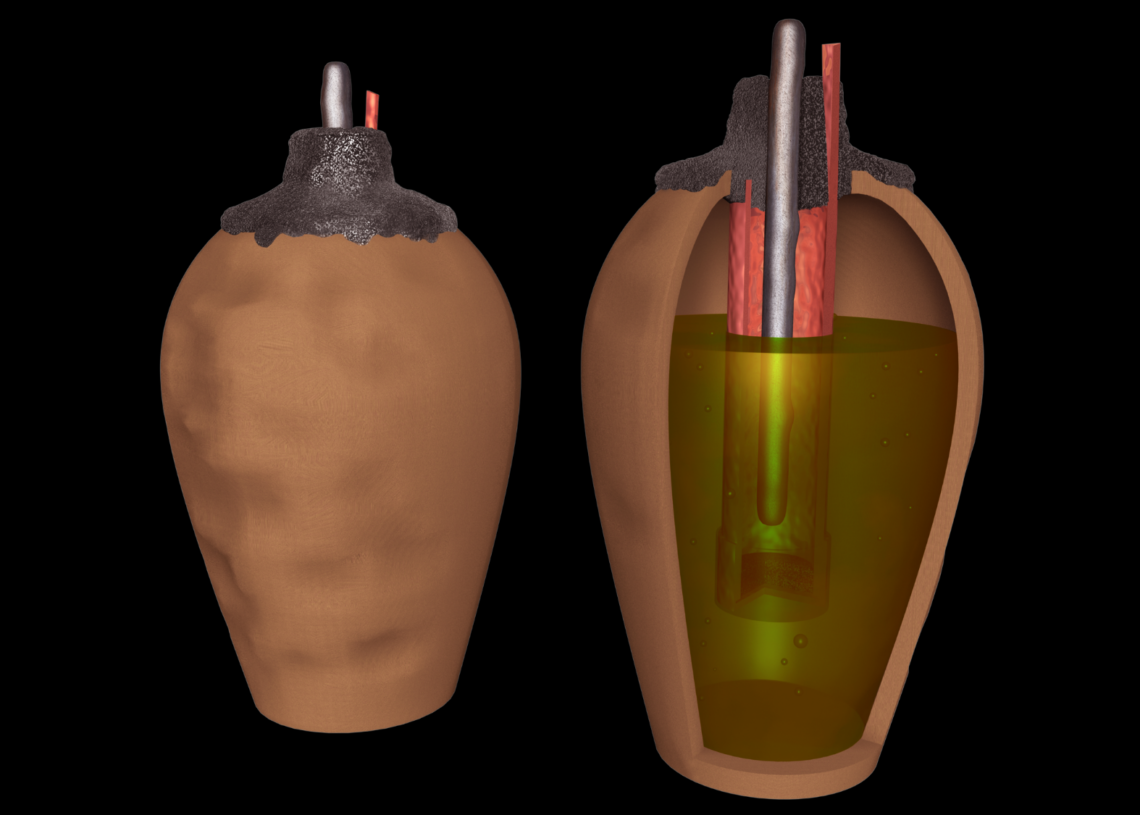

Unfortunately, we can’t study it anymore to try to come up with an answer, not since it was lost in the disastrous 2003 invasion of Iraq. Luckily, we have enough evidence to keep archaeologists debating about its purpose for the rest of time. It was a clay jar containing a copper cylinder and an iron rod, a setup that bears a close resemblance to a galvanic cell, the same basic principle behind modern batteries. The idea that people 2,000 years ago might have stumbled into the basic principles of modern electricity has been tantalizing archaeologists ever since.

A new study out of the University of Pennsylvania, highlighted by Chemistry World, adds a fresh — ahem — jolt to the argument. Independent researcher Alexander Bazes reconstructed the artifact and claims it could have produced up to 1.4 volts of power, roughly the output of a modern AA battery. His model suggests the jar’s porous clay could have acted as a separator, allowing an electrolyte like lye to interact with the metals and generate a usable electrical series.

Ancient Battery or Religious Ritual Object?

That’s a lot more power than people thought it was capable of producing, especially the ones who didn’t think it was anything even close to a battery at all. But Bazes is cautious not to take his prediction too far into the realm of science fiction. He also rejects a popular theory that suggests the device might have been used to electroplate jewelry. He has a different theory, one grounded in something more human: ritual. According to Bazes, the battery may have been designed to visibly corrode written prayers, offering worshippers physical proof that some unseen force had accepted their message.

Representing the anti-battery side of the argument, the chemistry world spoke with University of Pennsylvania archaeologist William Hafford, who argues that the object seems much closer to traditional sacred prayer jars and batteries. Similar vessels found by archaeologists include jars stuffed with multiple copper vessels, way too many to function electronically, that have been found in and around Iraq. The Baghdad battery is probably just another one, he argues. The supposed iron “electrode” was no electrode at all, maybe just a nail, part of a magical sealing ritual before the jar was buried as an offering to underworld deities. Still, very cool, but no ancient battery.

The debate rages on, and probably will for years to come.

The post Is This 2,000-Year-Old Artifact Actually a Battery? appeared first on VICE.