President Donald Trump announced Friday that he would nominate Kevin Warsh as the next chair of the Federal Reserve to succeed Jerome H. Powell, whose term expires in May.

Powell has been under constant attack by Trump for not lowering interest rates as aggressively as the president would like.

“I have known Kevin for a long period of time and have no doubt that he will go down as one of the GREAT Fed chairman, maybe the best,” Trump wrote on his social media platform Friday morning. “On top of everything else, he is ‘central casting,’ and he will never let you down.”

Who is Kevin Warsh?

Warsh, 55, is a Wall Street veteran who served as a Fed governor from 2006 to 2011 and was seen as a key liaison between the central bank and Wall Street during the great financial crisis.

Warsh began his career in 1995 at Morgan Stanley, where he worked as a mergers and acquisitions banker. He was also an economic adviser to President George W. Bush.

He is a partner at the family office of investor Stanley Druckenmiller and is a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Warsh is married to Estée Lauder heiress Jane Lauder.

What has Warsh said about the Fed?

Warsh has been critical of the Fed, saying the central bank undermined its own credibility by failing to keep inflation in check during the pandemic and by pursuing initiatives he characterized as accommodating political priorities, including work on climate-related issues.

“The Fed’s current wounds are largely self-inflicted,” he said last spring in Washington when competition to replace Powell was already heating up. “It’s high time we reclaim intellectual freedom and get policy back on track.”

What does he think about interest rates?

After years of a “hawkish” stance on inflation — favoring higher interest rates to prevent prices from rising — Warsh has recently changed his tune, saying the Fed should lower rates. Trump has also made it clear that cutting borrowing costs should be the next Fed chair’s top priority.

“I think until there’s until there is regime change at the Fed, and new people running the Fed — [with] a new operating framework — they are stuck with their own mistakes,” Warsh told Fox Business in October, praising Trump’s policies for curbing inflation.

Still, Warsh could face resistance within the Fed if he moves to cut interest rates as aggressively as the president has demanded. The Fed kept rates on hold this week for the first time since July, and Powell signaled that the committee is in no rush to lower them further in coming months. The Fed’s December forecast penciled in a median of just one rate reduction for 2026.

How are markets reacting?

Very calmly. Financial markets edged lower but were largely unchanged Friday following Warsh’s nomination. The 10-year Treasury yield, which moves opposite to its price, also barely budged.

Investors largely think of Warsh as a credible pick who’s more likely to be politically independent than others who were being considered for the job, such as Kevin Hassett, director of Trump’s National Economic Council.

“Warsh is a safe pick,” Jeffrey Roach, chief economist for LPL Financial, wrote in a note to clients Friday. “Investors should be thankful.”

What would a Fed rate cut mean for Americans?

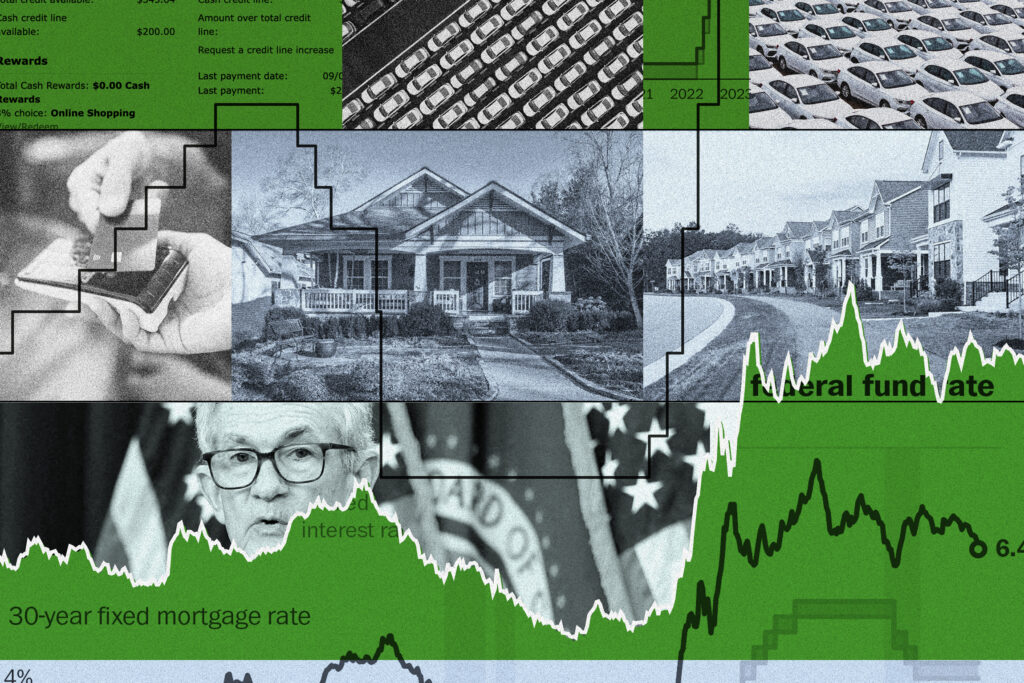

The Fed’s action sets the federal funds rate, or the standard rate for how banks borrow money from each other. That means banks can consider charging customers a lower interest rate and still make a profit because they are paying less to borrow the money in the first place.

But that doesn’t directly change what banks charge customers to borrow money for, say, small-business loans or car loans. The Fed’s rates are short-term, and while it influences longer-term loan rates, it does not control them.

If the Fed were to cut rates under Warsh, the amount of movement depends on the type of loan you’re considering.

Fed rate changes often have a more direct effect on shorter-term loans, or loans with variable rates, such as adjustable-rate mortgages. Those rates can move up and down as the Fed’s rate does. Car loans reflect a type of borrowing that may be partially but not directly influenced by the Fed’s rate. Banks also look at what the Fed says about what could be coming ahead to set rates.

Auto loan interest rates tend to be more responsive to the Fed than mortgage rates, with shorter-term loans matching the Fed’s rate cuts more closely. But car loans are also sensitive to the market dynamics of the auto industry, so rates often stay high when many people are applying.

Fed rate changes have a stronger influence on short-term interest rates, like those on credit cards or savings accounts. Interest rates on credit card debt may fall slightly in relation to a Fed rate cut. That could provide some relief to consumers who carry a balance from one month to the next, which is nearly half of all American cardholders, according to a 2024 survey.

Would a lower federal funds rate make it cheaper to buy a house?

Not necessarily. Mortgages tend to be long-term loans and don’t always move in step with the Fed’s actions.

Fixed-term mortgage rates are more influenced by Treasury bond yields, which are determined by investors’ views of the economy as a whole. Those bond yields can run in the opposite direction of Fed rate changes. When the Fed cut rates late last year, Treasury yields — and mortgage rates — did not follow. Instead they rose, as investors worried about potential upcoming inflation.

The average 30-year mortgage rate has fallen slightly in the past few months and is about 6.1 percent — down from 7.8 percent in 2023, but still far higher than 2.7 percent early in the pandemic — according to mortgage giant Freddie Mac.

Americans already locked into a fixed-rate mortgage — which is by far the most common arrangement in the United States — wouldn’t see a change. That mortgage rate stays the same over the 30- or 15-year lifetime of the loan, unless the borrower refinances. Fixed-rate mortgage rates have already dropped slightly this year, as the labor market weakens and demand in the housing market remains somewhat sluggish.

Alyssa Fowers and Rachel Lerman contributed to this report.

The post What a new Fed chair could mean for the economy appeared first on Washington Post.