The most striking thing about President Trump’s proposal for a “Board of Peace,” a new group he has billed as a global conflict-solving body, is not its billion-dollar permanent membership fee or the eccentric list of nations, such as El Salvador, Belarus and Saudia Arabia, that have apparently signed on. It’s that for the first time, the United States — the primary architect of the United Nations — is openly experimenting with a rival body at least nominally aimed at peacemaking. “I’m a big fan of the U.N.’s potential,” Mr. Trump said last week, “but it has never lived up to its potential.”

This move is best understood, though, not as a sudden break between the United States and the U.N., but as an accelerant. It is the latest chapter in a much longer history of America’s estrangement from its own creation, made possible by a global forgetting, often willful, of how war was once restrained.

For much of the postwar period, the United Nations helped prevent crises from spiraling into wider war, acting as a firewall when bilateral diplomacy failed. As much of that history has faded from view, political leaders from around the world have come to think of the U.N. as an obsolete talking shop of empty words. This amnesia has narrowed the horizons of those shaping foreign policy, leaving them unable to envision a security framework that isn’t a zero-sum game of rival blocs. If we continue to let ourselves forget the lessons of the mid-20th century, when the U.N. was a successful bulwark against conflict escalation, we will find ourselves unable to imagine the kind of international cooperation needed to prevent future catastrophes.

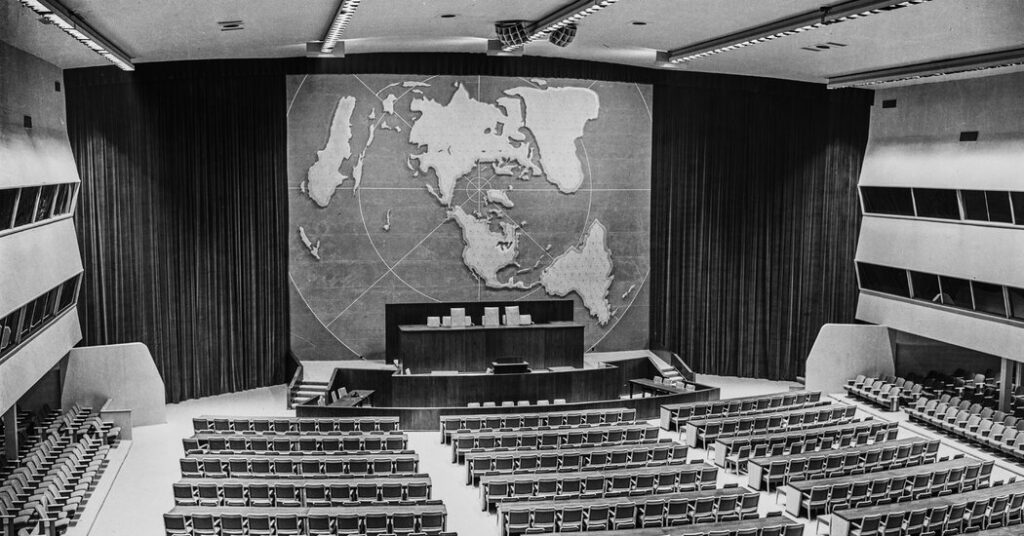

Just over 80 years ago, the United Nations was established by men and women who had lived through the deaths of tens of millions across two world wars. It was not a utopian project but a practical effort by battle-hardened founders alarmed by the destructive potential of the atomic age to permanently remove war as a tool of international relations. They believed a new kind of politics was possible, and sought to create a body that could impose discipline on the use of force, institutionalize multilateral diplomacy, safeguard state sovereignty and foster the economic conditions essential for stability.

Much of the world signed on. In its first few decades, dozens of newly independent states from Asia and Africa that had been shaped by decades of anticolonial struggle joined the United Nations, transforming it into humanity’s first near-universal body. Although the Security Council, with China, France, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union as veto-wielding permanent members, was often deadlocked by the politics of the Cold War, a surge of ambition from the new so-called Third World energized the U.N., turning its secretaries general into the world’s pre-eminent peacemakers.

For a time, they were remarkably effective. In 1956, Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold helped prevent the Suez crisis from intensifying into a great-power war by deploying the U.N.’s first peacekeeping operation. In 1962, his successor, U Thant (my grandfather) proved indispensable in de-escalating the Cuban missile crisis, mediating between John F. Kennedy, Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro — a part of the story that has been almost entirely erased from popular memory. A year later, in Congo, an Indian-commanded U.N. force under Thant’s authority routed a Belgian-backed secessionist army buttressed by white-supremacist mercenaries, protecting the newly independent state from dismemberment. Over the following years, Thant and his deputy, Ralph Bunche, helped end or contain half a dozen conflicts, from Cyprus to Kashmir.

Throughout this period, the United Nations enjoyed overwhelming support among American political leaders and the U.S. public. Washington was comfortable with an organization that seemed broadly aligned with, or at least did not obstruct, its own desires to strengthen American military and economic primacy around the world.

Eventually, though, the U.N. started to become unfashionable in Washington — not because it was ineffective, but because it began to take opposing positions on what were seen as core American interests. The first decisive break came in the mid-1960s over Vietnam, when Thant publicly challenged the war, questioned its strategic assumptions and pressed for a negotiated settlement, provoking the ire of President Lyndon B. Johnson and hawks on Capitol Hill. The 1967 Arab-Israeli war marked another turning point. In its aftermath, the U.N.’s push for a Middle East accord that included a full Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories fueled a growing belief among many Americans that the organization was institutionally biased against the Jewish state.

In the 1970s, efforts among developing nations within the U.N. to fashion a fairer global economy through commodity agreements, technology sharing and development financing were judged inimical to the globalization of U.S.-anchored free markets. Tensions also emerged in the body over Washington’s opposition to action against apartheid South Africa throughout much of the 1970s and 1980s, when the United States favored more conciliatory policies over the sweeping sanctions that the U.N. General Assembly demanded.

Throughout the 1980s, even as Washington’s focus pivoted further away from the global body, Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar and his team of veteran mediators quietly unlocked peace accords in conflicts in Central America, Southern Africa and Cambodia. In the process, they ensured that the proxy wars unfolding in these countries would not continue to poison superpower relations, setting the stage for an end to the Cold War.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 ushered in an era of American global supremacy. But the triumph of this U.S.-led so-called liberal international order also required that the achievements of an earlier, more internationalist order centered explicitly on the United Nations be quietly slipped down the memory hole. As the U.N. was increasingly retooled by the United States and other Western countries as a technocratic mechanism for managing faraway civil wars, largely through humanitarian aid and peacekeeping operations, its previous role as a mediator between states withered from view. What emerged was an institution deeply enmeshed in the U.S.-led order but peripheral to the strategic thinking of policy elites in capitals everywhere.

War and instability are once again on the rise, as is the risk of nuclear confrontation. We’ve suffered periods of intensified conflict and great-power rivalry many times since 1945. But for the first time since the Second World War, we are confronting these crises amid the near-complete erosion of the U.N. norms, institutions, and practices that, however imperfectly, constrained escalation and identified pathways to negotiated resolution. Only reinvestment in a radically remade U.N. — not Mr. Trump’s Board of Peace, whatever its ultimate remit — can fill that void.

Peace cannot be improvised. It needs to be designed, carefully and deliberately. An international politics unmoored from the core U.N. principles of universality, sovereign equality and clear limits on the use of force, combined with a collective amnesia about how wars were once prevented, can lead only to our sleepwalking back into the cataclysmic bloodshed of the early 20th century.

Thant Myint-U is a historian and the author of “Peacemaker: U Thant and the Forgotten Quest for a Just World.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post The World Used to End Wars. Why Did We Stop? appeared first on New York Times.