Back in 2023 when ChatGPT was still new, a professor friend had a colleague observe her class. Afterward, he complimented her on her teaching, but asked if she knew her students were typing her questions into ChatGPT and reading its output aloud as their replies.

At the time, I chalked this up to cognitive offloading, the use of A.I. to reduce the amount of thinking required to complete a task. Looking back, though, I think it was an early case of emotional offloading, the use of A.I. to reduce the energy required to navigate human interaction.

You’ve probably heard of extreme cases where people treat bots as lovers, therapists or friends. But many more have them intervene in their social lives in subtler ways. On dating apps, people are leaning on A.I. to help them seem more educated or confident; one app, Hinge, reports that many younger users “vibe check” messages with A.I. before sending them. (Young men, especially, lean on it to help them initiate conversations.)

In the classroom, the domain I know best, some students are not just using the tools to reduce effort on homework, but also to avoid the stress of an unscripted conversation with a professor — the possibility of making a mistake, drawing a blank or looking dumb — even when their interactions are not graded.

Last fall, The Times reported on students at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who cheated in their course, then wrote their apologies using A.I. In a situation where unforged communication to their professors might have made a difference, they still wouldn’t (or couldn’t) forgo A.I. as a social prosthetic.

As an academic administrator, I’m paid to worry about students’ use of A.I. to do their critical thinking. Universities have whole frameworks and apparatuses for academic integrity. A.I. has been a meteor strike on those frameworks, for obvious reasons.

But as educators, we have to do more than ensure that students learn new things; we have to help them become new people, too. From that perspective, emotional offloading worries me more than the cognitive kind, because farming out your social intuitions could hurt young people more than opting out of writing their own history papers.

Just as overreliance on calculators can weaken our arithmetic abilities and overreliance on GPS can weaken our sense of direction, overreliance on A.I. may weaken our ability to deal with the give and take of ordinary human interaction.

A generation gap has formed around A.I. use. One study found that 18- to 25-year-olds alone account for 46 percent of ChatGPT use. And this analysis didn’t even include users 17 and under.

Teenagers and young adults, stuck in the gradual transition from managed childhoods to adult freedoms, are both eager to make human connection and exquisitely alert to the possibility of embarrassment. (You remember.) A.I. offers them a way to manage some of that anxiety of presenting themselves in new roles when they don’t have a lot of experience to go on. In 2022, 41 percent of young adults reported feelings of anxiety most days.

Even informal social settings require participants to develop and then act within appropriate roles, a phenomenon best described by the sociologist Erving Goffman. There are ways people are expected to behave on a date, or in a grocery store, or at a restaurant, and different ways in different kinds of restaurants. But in certain situations, like starting at a new job or meeting a romantic partner’s family, the rules aren’t immediately clear. In his book “The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life,” Dr. Goffman writes:

When the individual does move into a new position in society and obtains a new part to perform, he is not likely to be told in full detail how to conduct himself, nor will the facts of his new situation press sufficiently on him from the start to determine his conduct without his further giving thought to it.

When we take on new roles — which we do all our lives, but especially as we figure out how to become adults — we learn by doing, and often by doing badly: being too formal or informal with new colleagues, too strait-laced or casual in new situations. (I still remember the shock on learning, years later, that because of my odd dress and awkward demeanor, my friends’ nickname for me freshman year was “the horror child.”)

Dr. Goffman was writing in the mid-1950s, when more socializing happened face-to-face. At the time, writing was relatively formal, whether for public consumption, as with literature or journalism, or for particular audiences, as with memos and contracts. Even letters and telegrams often involved real compositional thought; the postcard was as informal as it got.

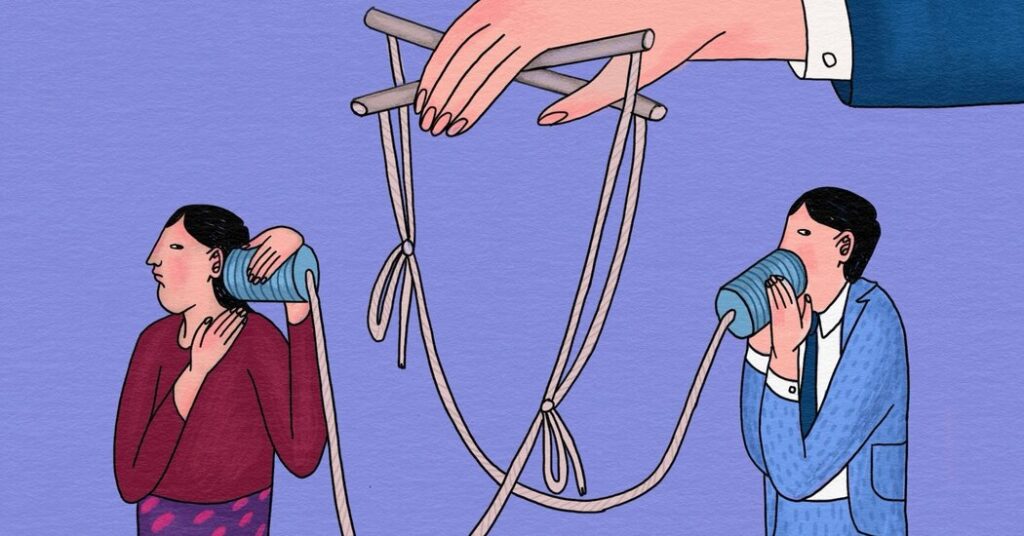

That started to change in the 1990s, when the inrush of digital communications — emails, instant messages, texting, Facebook, WhatsApp — made writing essential to much of human interaction, and socializing much easier to script. The words you send other people are a big part of your presentation of self in everyday life. And every place where writing has become a social interface is now ripe for an injection of A.I., adding an automated editor into every conversation, draining some of the personal from interpersonal interaction.

At a recent panel about student A.I. use hosted by high school educators, I heard several teens describe using A.I. to puzzle through past human interactions and rehearse upcoming ones. One talked about needing to have a tough conversation — “I want to say this to my friend, but I don’t want to sound rude” — so she asked A.I. to help her rehearse the conversation. Another said she had grown up hating to make phone calls (a common dislike among young people), which meant that most of her interaction at a distance was done via text, with time to compose and edit replies, which was time that could now include instant vibe checks.

These teens were adamant that they did not want to go directly to their parents or friends with these issues and that the steady availability of A.I. was a relief to them. They also rejected the idea of A.I. therapists; they weren’t treating A.I. as a replacement for another person but instead were using it to second-guess their own developing sense of how to treat other people.

A.I. has been trained to give us answers we like, rather than the ones we may need to hear. The resulting stream of praise — constantly hearing some version of “You’re absolutely right!” — risks eroding our ability to deal with the messiness of human relationships. Sociologists call this “social deskilling.”

Even casual A.I. use exposes users to a level of praise humans rarely experience from one another, which is not great for any of us, but is especially risky for young people still working on their social skills.

In a recent study (still in preprint) with the evocative title “Sycophantic A.I. Decreases Prosocial Intentions and Promotes Dependence,” six researchers from Stanford and Carnegie Mellon describe some of their conclusions:

Interaction with sycophantic A.I. models significantly reduced participants’ willingness to take actions to repair interpersonal conflict, while increasing their conviction of being in the right. However, participants rated sycophantic responses as higher quality, trusted the sycophantic A.I. model more and were more willing to use it again.

In other words, talking to a fawning bot reduces our willingness to try to fix strained or broken relationships in the real world while making the bot seem more trustworthy. Like a cigarette, those conversations are both corrosive and addictive.

More of this is coming. Most every place where humans are offered mediated communication, some company is going to offer an A.I. as a counselor, sidekick or wingman, there to gas you up, monitor the conversation or push certain responses while warning you away from others.

In the business world, it might be presented as an automated coach, in day-to-day interactions a digital friend, in dating it will be Cyrano as a service. Because user loyalty is good for business, companies will nudge us toward rehearsed interactions and self-righteousness when interacting with real people, and nudging them to reply to us in kind.

We need good social judgment to get along with one another. Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment. It sounds odd to say that we have to preserve space for humans to screw up socially, but it’s true.

The generation gap means the people in charge, mostly born in the last century, are likely to underestimate the risks from A.I. as a social prosthetic. We didn’t have A.I. as an option in our adulthood save for the last three years. For a 20-year-old, however, the last three years is their adulthood.

One possible response to sycophantic A.I. is simply to shift back to a more oral culture. Higher education is already shifting to oral exams. You can imagine adapting that strategy to interviews; new hires and potential roommates could be certified as “comfortable communicating without A.I.” (A new role for notary publics.) Offices could shift to more live communication, to reduce workslop. Dating sites could do the same, to reduce flirtslop.

A.I. misuse cannot be addressed solely through individuals opting out. Although some young people have started intentionally avoiding A.I. use, this is more likely to create a counterculture than to affect broad adoption. There are already signs that “I don’t use A.I.” is becoming this century’s “I don’t even own a TV” — a sanctimonious signal that had no appreciable effect on TV watching.

We do have a contemporary example of taking social dilemmas caused by technology seriously: the smartphone. Smartphones have good uses and have been widely adopted by choice, like A.I. But after almost two decades of treating overuse as a question of individual willpower, we are finally experimenting with collective action, as with bans on phones in the classroom and real age limits on social media.

It took us nearly two decades from the arrival of the smartphone to start instituting collective responses. If we move at the same rate here, we will start treating A.I.’s threat to human relationships as a collective issue in the late 2030s. We can already see the outlines of emotional offloading; it would be good if we don’t wait that long to react.

Clay Shirky is a vice provost at New York University.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Students Are Skipping the Hardest Part of Growing Up appeared first on New York Times.