“You’re seriously asking for my view on The English Patient?!” the late author David Foster Wallace squirms, midway through a lengthy 1997 PBS interview with Charlie Rose.

The host had been grilling Wallace, ostensibly invited on to discuss his own literary and journalistic output, on range of topics: tennis, teaching, why women don’t like Westerns, depression, and, yes, Anthony Minghella’s Academy Award-winning epic war drama, which had by the time the interview aired already become a Seinfeld punch line.

Watching the interview, it’s clear Wallace, who died by suicide in 2008, bristles at being pressed to purvey rank punditry on the popular culture at large like some kind of dancing monkey. But the exercise revealed how Rose, and large swaths of American intellectual culture circa the late-1990s, thought of Wallace. He was an all-purpose Big Brain who could alight on anything, from politics, to avant-garde authors, to the ethics of shellfish eating, to warmed-over Oscar bait. It is a consummate performance of erudition, shot through with prickly self-consciousness— arguably as impressive, and influential, as Wallace’s whole literary output.

February marks the 30 years since the publication of Wallace’s magnum opus, Infinite Jest, which publisher Back Bay Books is celebrating with a new paperback edition. It is a strong candidate for the definitive American novel of the ‘90s.

A massively scaled epic (it clocks in at 1,079 pages, including 96 pages of “Notes and Errata”), the novel follows Hal Incandenza, a pot-addled teenage tennis prodigy, and a gaggle of other characters living in a near-futuristic North American Superstate, where the US, Canada, and Mexico have been congealed into the Organization of North American Nations. The marking of time itself has been subsumed by corporate interests, and companies bid for the naming rights to calendar years. (The bulk of the novel unfolds in the “Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment.”) The book takes its title from a plot-driving video cartridge deemed so addictively entertaining that it can effectively hypnotize and kill anyone who watches it.

Volleying between arch irony and deep sincerity, Infinite Jest draws from a wealth of literary and pop cultural wellsprings. Homer, The Bible, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, Joyce, DeLillo, William James, The Beatles, the Alcoholics’ Anonymous “Big Book” manual, M*A*S*H*, and the Nightmare on Elm Street movies are all, somehow, woven together. It is a kind of mega-text. And it spoke directly to generations of readers. Or, at least, to generations of certain kinds of readers.

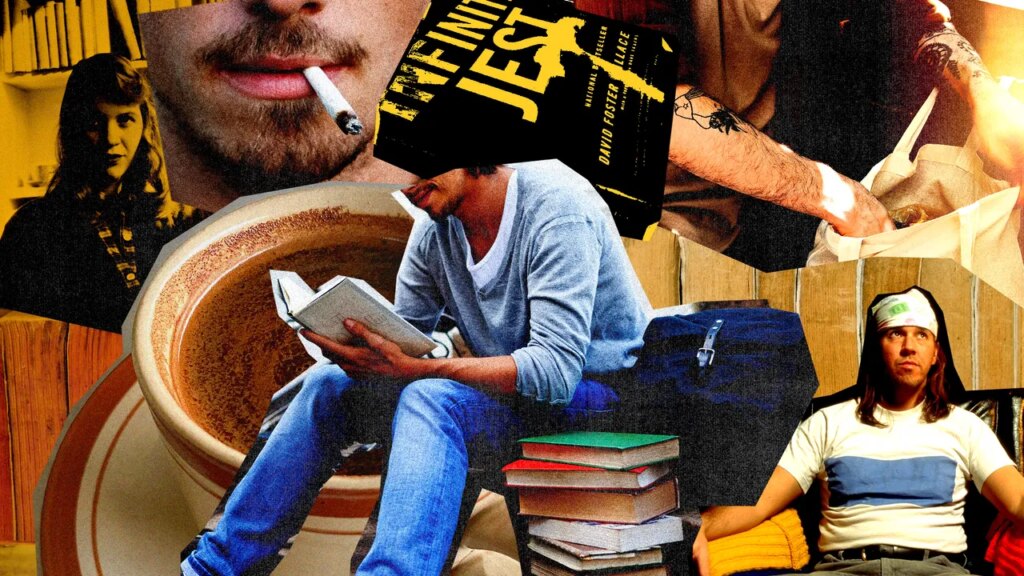

Infinite Jest is formidable. It is very thick. And—with its endnotes, high-minded vocabulary (quick: define “deuteragonist,” “brachiatishly,” or “kyphotic”), tricky narrative structure (the story’s climax is sneakily hidden in its very first chapter), and winding sentences, the longest of which runs some 600-plus words—it is also conspicuously “difficult.” Merely completing the book has become something like a literary merit badge. It has also, arguably, been a key text for a breed of reader who wears such badges with obnoxious pride. A type of reader who has himself become the stuff of mockery, misgiving, and near-infinite jest: the widely, and perhaps unfairly, maligned “litbro.”

“I’m not what you might consider Infinite Jest’s target demographic,” writes author and songwriter Michelle Zauner in her foreword to the newly struck 30th anniversary edition.

Zauner, best known as frontwoman of the band Japanese Breakfast, was initially egged to read the book by a guy she knew from school: “a notorious plagiarizer who used to pawn off Kerouac passages as his own in the school papers.” Litbro central casting, in other words.

Zauner describes Infinite Jest’s more typical fans as “a breed of college-aged men who talk over you, a sect of pedantic, misunderstood young men for whom, over the course of thirty years, Infinite Jest has become a rite of passage, much like Little Women or Pride and Prejudice might function for aspiring literary young women.”

As sketched across decades of literary discourse, the litbro is, roughly, a sullen male chauvinist drawn to challenging literature by male authors who proudly project an air of literary snobbery. For such readers, “DFW” is a rockstar. Many readers insisted Jeffrey Eugenides modeled the tobacco-chewing, bandana-wearing polymath from his novel The Marriage Plot after Wallace. Jason Segel played him in a movie. And watching him back in that Charlie Rose interview, hunched over in round wire-rim glasses, greasy strands of hair bound by a heavy white bandana, the author of Infinite Jest also seemed to epitomize such readers, and writers: brainy but a bit brawny, sad but funny, self-styled wunderkinder who can inveigh freely on smorgasbord of subjects.

The origins of literary machismo run back much further. Melville working whaling ships. Hemingway with the bulls. The whole generation of beat novelists and poets whose work drew from lives marked by adventure, and lots of drugs and alcohol. Classics of the litbro catalogue are often challenging, either on the level of prose (Gaddis, Pynchon, Bolaño) or content (Bret Easton Ellis’ gnarly Wall Street satire American Psycho, or Cormac McCarthy’s gruesomely violent western Blood Meridian).

Wallace is an interesting case here. His writing (mostly) avoids the titillations of sex and violence. And he wasn’t some romantic, or two-fisted literary drunk. (One of his most famous works of non-fiction is about getting bummed out on a Caribbean cruise. Not exactly Homage to Catalonia.) Instead, Wallace made stuff like reading a lot and being pedantic about grammar seem somehow cool. The Axl Rose headband probably helped. Cast in this mold, the lit bro treats their own library, jammed with dog-eared secondhand paperbacks, as a storehouse of cultural cachet.

The litbro was most memorably needled by the X account @GuyInYourMFA. The alter-ego of writer Dana Schwartz, the account lampooned pretentious white dudes in grad seminars eager to offer up tortured literary opinions. “The narrator of this short story is actually the concept of Time itself,” or “story idea: a man visits a prostitute.” The account was so popular that Schwartz parlayed it into a book, 2019’s The White Man’s Guide to White Male Writers of the Western Canon. The book promised to teach readers “everything you need to know to become the chain-smoking, coffee-drinking, Proust-quoting, award-winning writer you’ve always known you should be.”

Zauner identifies the “defining feature” of the litbro canon as male loneliness: “A white, male protagonist, isolated and misunderstood, stands at odds with social norms and expectations and either grapples internally to critique them or identifies the source of ideology and seeks violent revenge against it,” she writes.

Such a characterization seems to apply equally to these books’ protagonists, authors, and readers. Infinite Jest, in particular, is a book about a depressive prodigy, written by a depressive prodigy, pitched to an audience of readers who were probably depressed, and also probably considered themselves prodigies. The stereotypical Infinite Jest fanboy probably fancies themselves a bit like the anguished Hal who, early in the book, attempts to pitch himself to a judgy college admissions board, saying: “I read … I bet I’ve read everything you’ve read. Don’t think I haven’t. I consume libraries.”

This gleaming, know-it-all machismo can sometimes reveal a darker glint. Wallace’s own personal relationships were reportedly very volatile. Biographer D.T. Max described an account of the author attempting to push a girlfriend, author Mary Karr, out of a moving vehicle. He later threw a coffee table at her during an argument. Such attitudes also typify many of the litbro archetypes, both on and off the page. Jonathan Franzen has long been criticized for the way he writes, and speaks, about women. William S. Burroughs shot his wife in the head.

When it is not a defect of the authors themselves, such misogyny can bubble up at the basic level of writing and characterization. Case and point: the two most notable female characters in Infinite Jest are the controlling (and perhaps incestuous) matriarch nicknamed “The Moms,” and late night radio jockey Joelle van Dyne, who is known primarily for being “almost grotesquely lovely,” and is referred to acronymically as the “P.G.O.A.T.” for “Prettiest Girl of All Time.”

This strain of low-key sexism undergirds the litbro’s latest mutation: the so-called “performative male reader.” According to a lot of memes and a few trend pieces, it’s a new genus of litbro who doesn’t even read big books, he just peacocks with them for attention. Elsewhere, a whole class of online retailers have emerged to outfit anyone eager to project their literary cred, with Sylvia Plath long-sleeves, Dostoyevsky tote bags, and baseball caps stitched with the words “The Great American Novel.” Being “bookish” has itself become a kind of contemporary couture, or kitsch.

I am probably extra-sensitive to the whole litbro thing because I can be fairly accused of being one. I host a Thomas Pynchon podcast with my friend. A (very kind) write-up about it called us litbros. I own a Blood Meridian ball cap, and have a Goethe quote tattooed on my arm (in the original German, natch). In grad school, I wrote a paper about how Infinite Jest’s structure—and the experience of reading it, flipping between the main text and its linked endnotes—approximated internet-era hypertext. I even smoke cigarettes, though I am trying to smoke fewer of them. I understand that this all probably makes me sound pretty annoying.

Beyond my own predilections, the litbro strikes me as a phantasmic cultural creation. Do these books romanticize a form of pained, alienated, even self-pitying male genius? Certainly. Are chauvinistic and even—gasp!—pretentious male writers and readers roaming around out there in the wild? Sure. But most reliable indicators suggest they exist in a vanishingly small minority.

A 2022 survey from the National Endowment for the Arts reported that only about 28 percent of men read fiction. (The problem is compounded by the generalized decline in reading fiction, an issue the BBC recently responded with a podcast episode analyzing the “death of reading.”) Other reporting shows that women also publish more fiction than men.While think-pieces fret the litbro and the performative male, they also, simultaneously, fret the fact that “men don’t read fiction.” It’s a weird double-bind. You’re damned if you don’t read, but damned if you turn to a canon of literature targeted to your tastes and demographic identity.

Zauner writes that she undertook the task of reading and writing about Infinite Jest as part of an anthropological exercise to understand, “what it means to be a David Foster Wallace reader, which, at its worst, has come to signify misogyny, and at its best, someone who’s just slightly annoying.” Her appraisal of the book is perceptive and generous. She responds to Wallace’s clear-eyed prophecies about the future: from the reign of brain-dead celebrity politicians, to doom-scrolling media addiction, to the continued corporate subsidization of all of modern existence, if not time itself (yet). She also finds herself sympathizing not only with Wallace’s cast of doomed characters, but also with his readers: “people whom I realized were defined by a set of attributes wholly different than those I had assumed, people who had committed an act of defiance and tenacity, curiosity and right, and after it all, were sad to see its end.” The litbro, in her eyes at least, stands redeemed.

And why shouldn’t he be? Cast against a culture of Philistinism and flattening cultural horizons, a shallow performance of erudition and, heck, even snobbery, is surely preferable to wholesale illiteracy and a total disconnect from the world of fiction. There are worse things than a book, or author, daring to make difficult fiction seem cool, or even “macho.” And there is an increasingly rare pleasure afforded by getting sucked into a big, fat, funny, smart book that demands and rewards sustained attention.

In a culture where the literary novel holds about as much weight as the opera or stamp-collecting, it actually is kind of cool to devote one’s time, however unfashionably, to libraries, piled paperbacks, and dog-eared tomes bisected by multiple bookmarks; to snarl, like Wallace’s heroic Hal Incandenza: I read.

Just, you know, try not to be super-annoying about it.

The post ‘Infinite Jest’ Is Back. Maybe Litbros Should Be, Too appeared first on Wired.