SPERRYVILLE, Virginia — Doug Ward didn’t have a plan when he stopped working four years ago at age 72: “I was just going to retire.”

And so, after 35 years as a physician in Washington, he settled into a lakeside home here in rural Rappahannock County and set about doing … a whole lot of nothing.

“I was sitting here vegetating, and not real high-grade vegetating,” he recalled. “I was watching reruns on TV and spending hours on Facebook.”

Finally, his husband, Earl Johnson, had seen enough: “You need a hobby,” he told Ward.

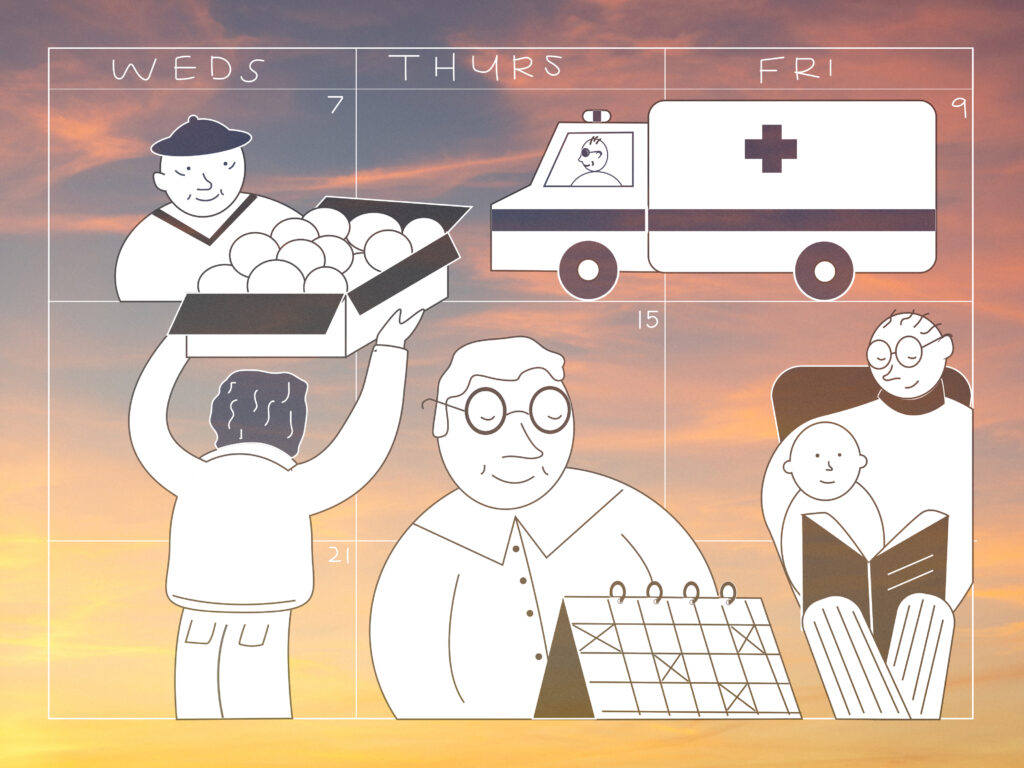

Two weeks later, the hobby found him. Ward suffered a severe allergic reaction to a yellow jacket sting, and the 911 dispatcher sent an ambulance from the Sperryville Volunteer Rescue Squad. Through the anaphylactic haze on the way to the hospital, it came to him. “Hey,” he thought, “I could do this.”

And he did. He studied to become an EMT and now works a weekly 12-hour shift for the rescue squad. Along the way, he rediscovered what he had been missing since leaving the workforce: his purpose. Ward, who served in the Peace Corps before a career treating AIDS patients, realized he missed serving others — and the rescue squad made him whole again. “I feel that I’m contributing,” he said.

Ward, who also gives his time to environmental groups, is part of the vanguard of 65-and-over super-volunteers who are reshaping the nature of volunteering — and aging — in America. As these seniors find their postretirement purpose in service, they are also discovering that it improves their health and well-being.

Researchers analyzing blood markers have recently discovered that volunteering appears to slow the aging process in seniors — a felicitous finding that adds to voluminous evidence that performing community service tends to improve things like mood and heart health, particularly for those of retirement age.

Many of these volunteers don’t yet know that there’s a biological benefit to their service. But they know that it boosts their mental health. In my conversations with members of the rescue squad, it quickly became apparent that, for all the heart attacks and car wrecks and broken hips they respond to, the people they’re really rescuing are themselves.

Martin Woodard, 75, the squad’s former chief, said his mental acuity is “a lot sharper” because his EMT certification requires him to “use my brain in ways that I hadn’t done for years.”

Paul Kirchman, 68, the current chief, told me he gets both an “endorphin rush” and “a feeling of fulfillment” in the ambulance. “You see people in pain, people scared, and you can do something about it. You don’t feel helpless.”

Brian Ross, who worked as a handyman and shopkeeper, finds redemption in the gratitude of the people he rescues. “For a long, long time, I partied and used anything that I could for good times, and so now I feel like I’ve got a way to give back,” said Ross, 72. “I feel like now I’m connected and I’m a good citizen, not just a waste.”

As many Americans live longer and stay healthier in their retirement years, seniors are volunteering at a higher rate than all other ages, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has found. The 65-plus group contributed 28.6 percent of volunteer hours worked in 2021, up from 18.5 percent in 2002, according to an analysis of census data by AARP and NationSwell. They are particularly active when it comes to informal, neighbor-to-neighbor volunteering.

The increased number of people in the 65-and-over cohort doesn’t account for the entire increase in volunteer hours. “There’s more of them and they’re volunteering at a higher rate,” said Nancy Morrow-Howell, a gerontologist who runs the Harvey A. Friedman Center for Aging at Washington University in St. Louis.

Voluntary associations, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed nearly two centuries ago, are fundamental to the American experiment, which makes the overall decline of volunteerism particularly worrisome. At a time when government support is shrinking, seniors now offer a critical supply of volunteer labor.

Rappahannock — which, like other rural areas, has limited government services — couldn’t function without its volunteer corps. In a county of 7,500 residents, there are perhaps 100 super-volunteers, mostly people in their 60s and 70s. They go from activity to activity: driving shut-in seniors to their doctor appointments, putting in shifts at the food pantry, mentoring for the public schools, preparing free tax returns, helping out at the library and the day care, picking up litter from roadsides.

Without the 30 volunteers on the Sperryville rescue squad (they far outnumber the few county-paid medics who rotate through the station), many a resident would die before reaching the nearest hospital, about half an hour away, or the nearest trauma center, an hour’s drive. These volunteers, only about five of whom are younger than 60, also help get people with limited mobility out of bed, change bandages, check blood pressure, do a load of laundry if needed or just provide human contact for the lonely.

In return, they get the gratitude of the community — and, it turns out, a whole lot more.

A 2025 study in the journal Social Science and Medicine found that those 62 and older who reported volunteering had blood markers showing slower epigenetic, or biological, aging. Slower aging on such “epigenetic clocks” is tied to greater cognitive, physical, metabolic, cardiovascular and immune functioning. The benefits were apparent among those who did even modest volunteering (one to 49 hours per year), and they were particularly strong for those who volunteered at least 200 hours a year and who were retired. This effect held up even when controlling for the tendency of volunteers to be healthier to begin with. It’s as simple as this, study co-author Cal Halvorsen told me: “People who are volunteering later in life are aging at a decelerated rate.”

This is on top of other research finding that older adults who volunteer have a lower risk of heart attack, lower blood pressure, fewer symptoms of depression and greater life satisfaction. Of course, volunteering is much easier for those who don’t have to earn money in old age, but a study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine found that older volunteers in the lowest wealth quintile reported greater gains from volunteering than those in the highest quintile.

This research is consistent with a whole other body of scholarship finding that people of all ages can improve their health and well-being by shifting their focus from internal to external. “The best thing you can do for yourself,” said University of Winnipeg psychologist Beverley Fehr, “is to reach out to others.”

But the effect is particularly crucial in retirement. If you don’t have something to give you a sense of purpose after you leave the workforce, “that can actually be bad for you psychologically, which over time can be very bad for you physically,” said Halvorsen, also of Washington University. Other meaningful activities, such as caring for grandchildren, can provide benefits similar to volunteering, Halvorsen added. “The question is, do you have something that you look forward to, that gives you a sense of meaning and purpose, especially outside of yourself?”

Your answer may hold the key to a healthy and happy old age.

One super-volunteer told me that what motivates retirees to work the equivalent of full-time jobs for free is FOEC: fear of an empty calendar. But the motivation goes well beyond avoiding boredom. There’s a sense of mutual aid, of paying it forward before needing help yourself. And there’s the deep sense of belonging and community. “It does give back to the giver,” said Tom Salley, a lawyer turned ambulance driver.

Suzanne Winter-Rose, an 84-year-old retired D.C. real estate agent, knows all about that. Each Saturday, she drives her Subaru up a rough Virginia mountain road to pick up 100-year-old Bess Lucking for their lunch date. On a recent trip to their favorite Italian spot, Winter-Rose helped the 94-pound centenarian into the passenger seat, tossed her walker in the hatchback, and settled into their weekly banter about dogs, children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Lucking is feisty — her first words to me were “I don’t want to be interviewed!” — but when I asked about her lunch partner, she beamed. “I love her!”

“The feeling is mutual,” Winter-Rose replied. She told Lucking she had “become a role model for me. I want to be just like you when I grow up.”

The 100-year-old on the mountain may be a role model for Winter-Rose, but Winter-Rose and the others I met while reporting this column are role models for me.

I want to be like Bob Hurley when I grow up. He’s 74 and has been fully retired for nine years after a career in government relations on Capitol Hill. But he keeps up an exhausting schedule.

He spends about 15 hours a week writing articles on behalf of a nonprofit, Foothills Forum, that run in the local paper. He drives the wheelchair van for Rapp at Home, taking people to appointments for hours at a time, as often as twice a week. He’s on the board of the Lions Club, a service group, and the Rappahannock League for Environmental Protection (RLEP). He monitors streams for pollution. He acts in the community theater. He’s a mentor to local children and volunteers at a camp for kids with cancer. He helps with the arts tour and the Christmas parade.

“Sometimes I scratch my head and say, ‘What the hell am I doing?’” Hurley said of his hectic schedule. “After all, I’m retired, right?” But he does it both because of the deep satisfaction he gets from helping and because the people he volunteers with have become the focus of his social life.

I also want to be like Steph Ridder when I grow up. A retired law professor, she volunteers for the Child Care & Learning Center, the Piedmont Environmental Council, Virginia Outdoors, Virginia Working Landscapes, the Flint Hill fire department, and the Rappahannock Food Pantry, and also serves as an elections worker and a tutor for high school students writing college essays.

And I want to be like Mike and Joyce Wenger. She’s a retired tech consultant who for years ran Rapp at Home, the equivalent of a full-time job. He’s retired after a career in the Air Force and as a consultant, and seems to show up at every volunteer event I attend.

He volunteers with the Old Rag Master Naturalists, monitors streams, drives a wheelchair van, and has served on the board of the Lions Club, the local community college and RLEP.

I shadowed him for a few days of his volunteer activities. We met at the Amissville Market where, over chicken soup, fresh bread and spreadsheets, he lobbied officials from Headwaters, a local public-education foundation, to fill a gap in funding for a program that pays for high school graduates to go to trade school.

Next we were at the county library for a meeting of the Blue Ridge Ukulele Circle, organized by Wenger. A dozen musicians, most of them of retirement age and apparently new to the ukulele, strummed and sang “Power of Kindness,” a folk song by MaMuse. “I’m feeling the funk already!” Wenger said brightly after a first attempt.

We also attended the fortnightly meeting of the Lions Club, where two women and about 40 men, also largely of retirement age, gathered for dinner at the firehouse. “I’m the new membership co-chair,” Wenger informed me shortly after I arrived.

“As of when?” I asked.

“Five minutes ago,” he answered.

He hadn’t been planning to do it, but the club secretary asked him, and he instantly agreed.

When Wenger, 74, moved to Rappahannock a decade ago, he figured he’d be reading novels and puttering around on his land. Instead, he seems to have befriended half the county. “Having lots of different irons in the fire works for me, in that I have something that I can do that’s important or meaningful,” he said. “It’s not saving thousands of people, but it’s helping one person. And the feedback loop for finding out that you were successful is quick. Gosh, how can that not be good for your mental health?”

Best of all, it required neither wealth nor skills to find fulfillment in retirement. “Just show up,” Wenger advised. “And say ‘yes.’”

The post Here’s a proven way to slow aging. Any volunteers? appeared first on Washington Post.