Regarding the Jan. 27 editorial “At last, some generational change in the DMV”:

In 2022, I ran for D.C. Council as a Republican. Shortly after losing the Ward 3 race, I changed my party to non-affiliated, or “independent.” Recently, however, I became a Democrat. It took me three minutes on the D.C. Board of Elections website. I hope tens of thousands of non-affiliated and Republican Washingtonians join me and vote in D.C.’s June Democratic primary. Here’s why.

In 2024, Initiative 83 passed by a sweeping 73 percent to 27 percent and won a majority of voters in every ward. The D.C. Council funded implementation of ranked-choice voting, the first part of the initiative, but it chose to deny voters the second, more significant Initiative 83 reform: opening our primary elections. The council did this, I believe, to protect Democrats’ political monopoly in D.C. Well, if you can’t beat them, join them.

Roughly 96,000 of D.C.’s registered voters, about 18 percent, are non-affiliated, and roughly 30,000 are registered as Republicans. These voters do not wish to be Democrats, but they should, because the capital’s leadership is about to significantly change for the first time in decades. Eleanor Holmes Norton, who has been the District’s delegate to Congress for 18 terms, is retiring. And Mayor Muriel E. Bowser is opting not to run for a fourth term after more than a decade of leadership.

Except for the second at-large council position, the general election in D.C. is meaningless. The Democratic primary is everything. So I urge the more than 100,000 non-Democratic D.C. voters to follow my lead. You can change your affiliation back in July.

David Krucoff, Washington

Love letters to love letters

I enjoyed the Jan. 25 letters package “Heirlooms without price,” about interviewing your parents and other methods of capturing family history.

Every September, I pick some aspect of the family past, dig through the old albums, let my memories go to work and write a short book about it, complete with pictures. One year, I wrote about when the whole family moved because my dad had changed jobs. I was 15, and my dad and I drove from Utah to Miami and lived together for several months. Another year, I wrote about memories of Boy Scouts, centered on a pearl-handled knife I found on a campout and still have. This year was random stuff around the house that had long histories — my mom’s old potato masher, souvenirs from a work trip to Germany the year after the Wall fell, and so on.

This piecemeal approach makes writing history easier. It’s all but impossible for anyone to sit down and “tell us about the old days, Grandpa,” but if you pick one aspect — a day at the zoo, that stash of letters your mom and dad wrote each other while courting — it helps you focus and makes a nice little book. I’ve given my sons more than 20 of these books now, and they say it’s the one Christmas gift they really look forward to.

Charles Trentelman, Ogden, Utah

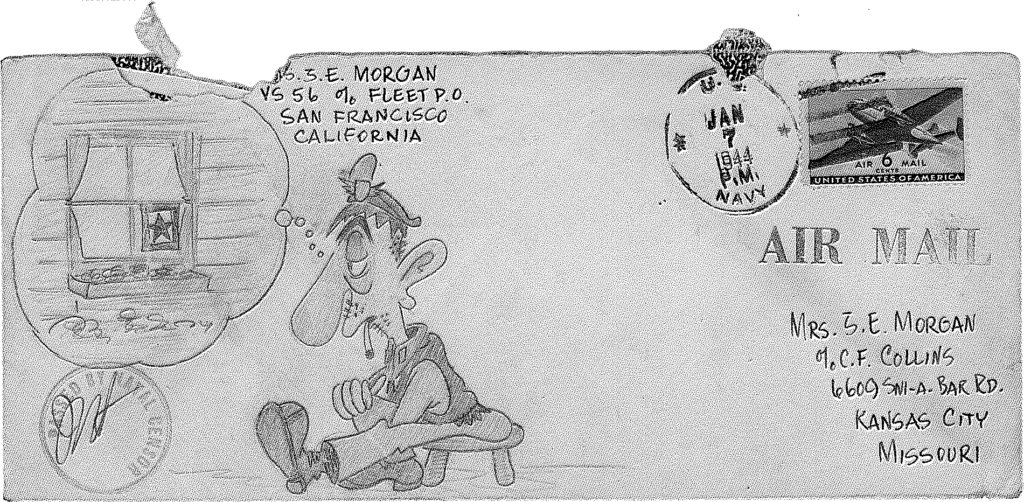

My grandfather, Joe Morgan, was publisher of the newspaper in Excelsior Springs, Missouri, a town our family has been part of since before it even had a name. My grandfather wrote a column called Those Were the Days, capturing memories of the community as he experienced it.

His own life felt almost mythic. He was born in a bathhouse downtown and died just a block away in what had also been a bathhouse. Overseas during World War II, he wrote letters home to my grandmother, often with cartoon versions of himself depicting his life in the military. When the letters began arriving late, my grandmother asked about it and learned that postal workers were passing them around so everyone could see the drawings. Only the envelopes remain today. My grandmother took the letters to her grave.

Late one evening after a family gathering, my husband and I asked my grandfather if he would let us interview him. We recorded the conversation, and I asked him about everything. He later gave me copies of all his columns. He also entrusted me with the family photo archive. Before dividing the photos among relatives, I scanned every image. One Christmas, I gathered everyone around the television and played a slideshow. They had no idea what they were about to see. Childhood photos of my aunts and uncles, images they had never seen before, memories long forgotten. There were tears that night.

Courtney Cole, Excelsior Springs, Missouri

When I was a kid, my mother’s family held reunions every five years, but my father’s family had only had one reunion. It became argumentative and was never repeated.

It took me years to find out why nobody wanted to tell me anything: My grandfather’s grandfather had killed a man. A cousin and I were collaborating on family history research, and neither of us knew about the murder. We also didn’t know that our great-great-grandfather had not married our great-great-grandmother, his first “wife.” They traveled together posing as a married couple for about 25 years in the mid-1800s. Then he up and married her niece, and the man he later killed was the niece’s lover.

There is a great deal about our family in government records because both “wives” applied for his pension from the Civil War and there was a long set of affidavits taken. I wish I had known this years earlier, when there were people alive who could give their personal remembrances, instead of reading about it in competing pension applications.

Now I tell people who want to look into their history, “Be prepared, because you never know what you will find.” But I don’t tell them not to look, because what I found out explained a lot.

J.L. Rhinehart, Spartanburg, South Carolina

The post Fellow Republicans, join me in becoming a Democrat appeared first on Washington Post.