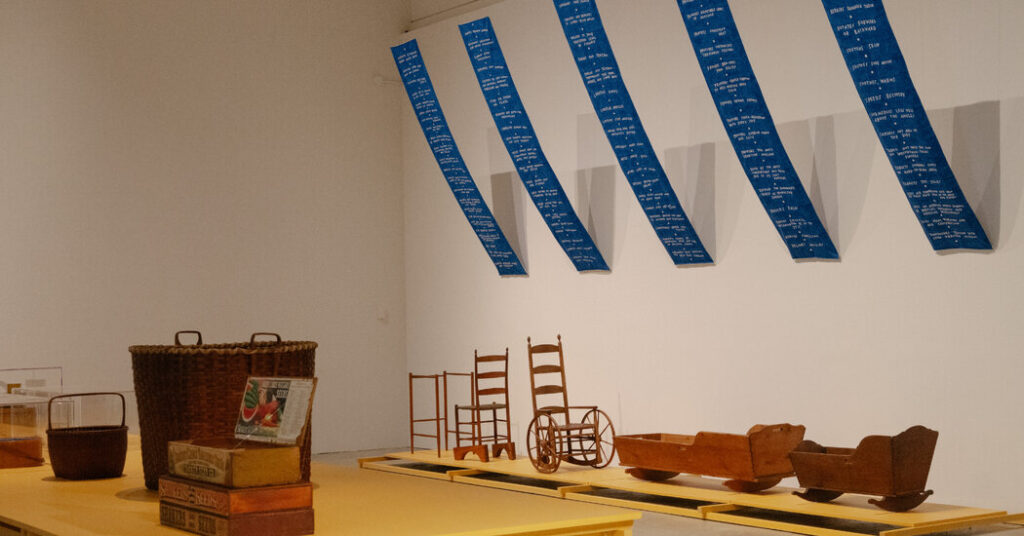

Thin-walled oval boxes. Straight-backed chairs with slender limbs. Storage cabinets with a profusion of neatly stacked drawers. Many of the objects here are so familiar that their nuanced origins have been left in the sawdust.

“A World in the Making: The Shakers,” which opens Saturday at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) at the University of Pennsylvania, is the latest museum show to honor the material culture of the Shakers, the utopian sect famous for their communal living, pacifism, celibacy and ecstatic worship.

At its height in the mid-19th century, the group, officially known as the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, had about 5,000 members. Today it has two, plus a provisional third member, who joined last spring and is working through a five-year trial period.

The Shakers are celebrated for their austere domestic objects, which are widely viewed as precursors of modern design. Yet by highlighting Shakers’ technological and commercial skills, “A World in the Making” pushes far beyond the popular view of the society as handy people who hung their chairs on peg rails and planted the seeds for home furnishings catalogs promoting “Shaker style.”

Among the show’s more than 150 items are packages for pioneering seed businesses, velvet-trimmed sewing boxes marketed to luxury-loving needlewomen and a 1920s radio assembled from mail-order parts.

“A World in the Making” is part of the surge of Shaker-inspired projects that go well beyond the oval box, with some refracted through modern interpretations that can be challenging. The traveling exhibition, a joint undertaking with the Vitra Design Museum in Germany, where it originated last summer, and the Milwaukee Art Museum, also presents works by seven contemporary artists, including a walk-in cardboard meetinghouse by Amie Cunat, funerary objects woven by Christien Meindertsma in the manner of Indigenous and Shaker baskets and a short film of dancers swaying to the choreography of Reggie Wilson, who was inspired by the ecstatic dancing of the early Shakers as well as the movement traditions of Black churches.

Its United States debut comes on the heels of “The Testament of Ann Lee,” a movie that dives into scenes of sex, childbirth and violence to depict the turbulent life of one of the sect’s early leaders. And it follows the recent appointment of Claudia Gould as the boundary-pushing new executive director of the Shaker Museum, in Chatham, N.Y. That institution, a steward of Shaker artifacts and archives, is the source for the historical objects in this show.

In April, ground was broken for a $30 million Shaker Museum extension designed by Annabelle Selldorf, the lead architect of the recent Frick Collection renovation in New York City. The new building, which was commissioned by Gould’s predecessor, Lacy Schutz, is scheduled to open in 2028.

Hallie Ringle, chief curator at the ICA, believes there is renewed relevance in the Shakers’ utopianism: “What does it mean to build tomorrow for today? That is the question that the Shakers have been asking since their inception, but it feels more contemporary than ever,” she said.

The show also homes in on the Shakers’ goal of communal living, where every gesture, every chore, not only contributes to the stability of the collective but is also a sacrament.

“We become interested in world building when the world is crumbling around us,” said Sarah Margolis-Pineo, a former curator at the Hancock Shaker Village museum in Pittsfield, Mass., who wrote an essay for this show’s catalog. “In this very last gasp of late-stage capitalism, I think people are interested in different forms of how we can live and be productive and find meaning together.”

Gould, who previously led the Jewish Museum in New York City, proposed that the current political climate, with its rejection of diversity initiatives and its frequent condemnation of immigrants and women, has drawn people to the positive values that are “equated with the Shakers,” she said.

The Shakers typically provided a safe harbor for anyone in need — enslaved people, hungry people, single mothers, orphans. Having reasoned that a god that created humankind in its image would have aspects that were both male and female, the group showed an extraordinary respect for gender equality from the beginning. Ann Lee, the Manchester, England-born visionary who founded the first Shaker settlement, near Albany, N.Y., in 1776, set an example that would be echoed by Rebecca Cox Jackson, a Black seamstress who established an African American Shaker community in Philadelphia in 1858.

“A World in the Making” includes two embroidered textiles designed by the artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed. The pieces refer abstractly to the writings of Jackson, who said that she learned to read in a swoop of divine intervention.

Monica Hampton, the executive director of the nonprofit Furniture Society, said that a general resurgence of interest in handicraft has led to a new appreciation of Shaker aesthetics, which are enveloped in the group’s spiritual values. Shaker design has long been admired, Hampton said, but it was co-opted by housewares companies in the 1980s and turned into a generic, cherry-wood or honey-glazed version.

Now, as Shaker “style” is refracted through modern interpretations, it bends and twists.

The Shaker Museum in Chatham has been actively encouraging contemporary artists to creatively mine the collection. One recent example initiated by Schutz, a traveling show curated by the actress Frances McDormand and the artist Suzanne Bocanegra, centered on an adult cradle, underscoring the tenderness with which the Shakers historically treated their elderly and infirm. (The cradle is now displayed in “A World in the Making.”)

Gould, a powerful cultural hybridizer — she famously brought together the artist Vito Acconci and the architect Steven Holl to renovate the Storefront for Art and Architecture in Lower Manhattan in the early 1990s — will continue inviting contemporary artists to build bridges with the museum.

This summer, a pop-up shop in Chatham called Shaker Outpost will sell Shaker-inspired goods by the artists Maira Kalman, Paula Greif and Kiki Smith. The two inaugural exhibitions in the new building will feature an artist in dialogue with Shaker objects and a choreographer, dancer and crafter.

Referring to the Shakers, she said, “Every object they made they infused with God and their own beliefs. Every object is a holy object in some way, similar to Judaica.”

The license to interpret, however, increases the danger of disrespect. One wonders what the historical Shakers would have made of the Shaker Museum’s agreement with David Nosanchuk, an industrial designer, allowing him to scan anything in its 18,000-object collection and 3-D print it in translucent colored resin. The project, called “Shaker Redux,” was authorized in 2023 but is still in the prototype stage.

For many, Shaker boxes and candlestands are the quintessence of woodworking. Plastic? Gould saw no contradiction.

“The Shakers were always ahead of their time,” she said, “and we don’t know what they would be doing if they came to America now.” (The Shakers were happy to use Bakelite, also a kind of plastic, for the control panel of the 1920s radio shown at the ICA.)

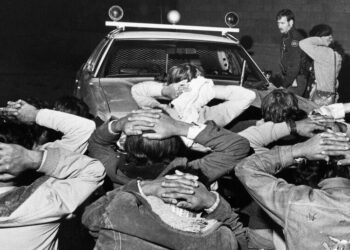

With “The Testament of Ann Lee,” the director and co-writer Mona Fastvold acknowledged playing loose with the chronology of Shaker designs and architecture. (The “Tree of Life” painting shown on a meetinghouse wall, for instance, which has become something of a Shaker meme, came to Hannah Cohoon, a member of Hancock Shaker Village, in a vision in 1854, 70 years after Mother Ann died.)

“I felt it was important to draw that line visually for the audience, because Ann Lee’s story is so unfamiliar to most,” Fastvold said in an interview.

More provocative was Fastvold’s decision to source the goal of Shaker celibacy in Mother Ann’s loss of all four of her children in their infancy. Though Mother Ann later preaches to her followers the importance of achieving a pure communion with God through chastity, she is presented as a woman who has taken control of her body and mind.

One harrowing film sequence shows visceral images of each birth and death. The portrayal of Mother Ann’s traumatic response, which landed her in a mental hospital, is based in fact, Fastvold said, noting extensive research that produced a portrait of a leader who was a “nurturing and caring kind of mother” and who aspired to “mother the whole world.”

Fastvold said that she did not consult with the two active Shakers at any point, saying it was out of respect: “For them it’s a living religion, and for me I’m telling a story about a historical figure.” She added, “I was worried I’d be too cowed by their interpretation of her story to not make space for my own.”

Before “The Testament of Ann Lee” opened, one of the active Shakers, Brother Arnold Hadd, posted an anticipatory video on a website that challenged the idea that the deaths of her children were at the root of Mother Ann’s insistence on celibacy. The deaths would have been expected, he said, because of the high incidence of infant mortality in her time.

Later, after he had seen the film, in an emailed response to a request for an interview, Brother Arnold declined to comment, explaining that it was “filled with lies and inaccuracies on a scale not imagined before.”

Told of his suggestion that people in the 18th century were more inured to the loss of their children, Fastvold said, “I think any mother would disagree with him.”

Before planning the ICA show with the Vitra Museum, Ringle, the curator, informally polled her family members and was startled to find most had not heard of the Shakers.

“I’m really excited to have people come in and understand who they were,” she said.

By displaying rarely shown Shaker goods, and not just what Brother Arnold described in a 2019 article in Mortise & Tenon Magazine as the “same 100 objects” that “are carted around from museum to museum,” this show aims to bolster such understanding. But to the living Shakers, there are always limits. “Shaker-made objects do not explain our faith,” Brother Arnold wrote. “Our life and actions explain it.”

A World in the Making: The Shakers

Opens on Saturday and runs through Aug. 9 at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania, 118 S. 36th Street, Philadelphia; icaphila.org.

The post The Shakers’ Utopian World Sees a Surge of Modern Interest appeared first on New York Times.