A long-lost “Judith Beheading Holofernes,” painted in 1606 by Caravaggio, recovered from under a mattress in an attic in 2014.

A Madonna and Child from the 1490s, by Pietro Perugino, saved from under a garage workbench last fall.

A Cimabue painting of the Virgin Mary, found hanging in a kitchen in 2019, almost 750 years after it was made.

Lost art comes crawling out of the woodwork once or twice a decade.

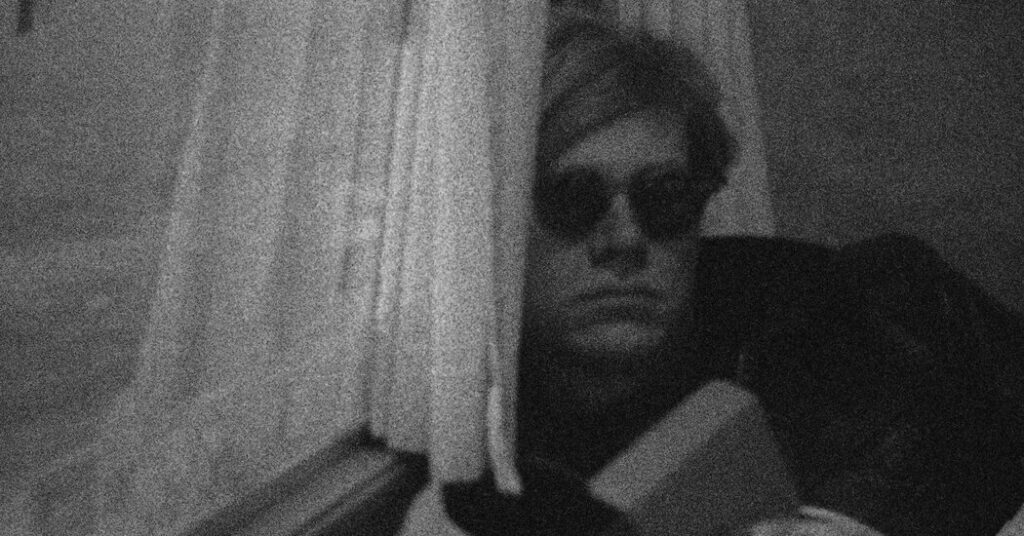

Dozens of works by Andy Warhol are the latest case, with one very notable difference: The artist himself never got to lay eyes on them.

On Feb. 2, at 6:30 p.m., in a one-time screening titled “Andy Warhol Exposed: Newly Processed Films From the 1960s,” the Museum of Modern Art will be revealing more than an hour of footage shot by Warhol and his team but not developed until 18 months ago.

The recovered work (I got a preview) includes eight new films from Warhol’s Screen Tests series, the four-minute filmed portraits that I have declared some of the most powerful, “Rembrandt-like images” you could ever see. There’s also charming footage of a couple gamboling in Central Park that might be some of the first scenes Warhol ever shot, not long after he got his movie camera in the summer of 1963: They’re so lighthearted and playful, they’re more in the spirit of his jaunty commercial drawings from the 1950s than of the deadpan Pop Art he was just then perfecting. And there are a number of reels of explicit sex that give new evidence for Warhol’s role in the sexual revolution of the 1960s.

Katie Trainor, who manages MoMA’s film collections, told me the story behind the new finds.

One day back in 2015, she and Greg Pierce, then the director of film and video at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, were at the facility in Pennsylvania where MoMA stores its Warhol films — since the artist’s death in 1987, almost all his footage has passed into that museum’s keeping — when they found something unexpected. “There was a box that we pulled out,” Trainor explained in a video call, “and faintly written on it, it said ‘raw stock’”— words that had always kept her colleagues from digging further, because unshot film from decades ago couldn’t be of much interest, even if Warhol was the one not to shoot it. But when Trainor and Pierce took a closer look, they realized that its 45 rolls of 16 mm film, each promising up to four minutes of action, bore every sign of having been exposed in Warhol’s camera. Some rolls even came labeled with their likely subjects. One was marked “Jerry & Girl,” promising new onscreen adventures from Warhol’s assistant, Gerard Malanga, who was known as a Lothario.

Another read, “3-12-66 Ann Arbor Car Ride” — pointing to the day that Warhol and his studio band, the Velvet Underground, rode a rented R.V. to a fabled concert at the University of Michigan.

And Pierce reminded Trainor that among the hundreds of other Warhol rolls stored by MoMA, a good number had been inventoried as “undeveloped” before being quietly ignored ever since.

The pair knew that all that ancient film might have had its images bleached away by time, but if they could get it processed, there was a chance it might yield fresh Warholiana.

Other projects intervened, however, so it took until the spring of 2024 for Trainor to finally entrust the undeveloped rolls to Colorlab, in the suburbs of Washington. Its owner, Thomas Aschenbach, “knows everything about film stock, ever,” according to Trainor.

It wasn’t the first time the lab had been called on to develop old footage, Aschenbach said in a phone interview. So he’d felt “kind of confident” that, so long as the Warhol rolls had been properly shot, images would still show up on them. His main question had been why the processing hadn’t happened back when the film was shot — a question no one may ever answer. Some blame probably lies with the sheer chaos of Warhol’s Silver Factory, and the sheer quantity of footage it churned out.

Of the 86 100-foot rolls Trainor sent to Aschenbach, more than half seemed either not to have been exposed at all or, in a few cases, to have been completely overexposed, as though someone had unspooled the film in bright light. Another 38 came out of the darkroom with imagery still remarkably intact despite six decades of storage. “I was blown away by how good it looked after that many years,” Pierce said. “I’m still kind of floored by that.”

As with most other cases of long-lost art, no unknown masterpieces emerged from Aschenbach’s chemicals.

The new Screen Tests come closest. Although they are of a piece with the other 472 films in that series, it’s obviously nice to have a few more — the way we wouldn’t complain if some new Rembrandts were added to the Dutchman’s vast portrait tally. On top of fresh portraits of the celebrated Warholians Dennis Hopper and Jane Holzer, each the subject of more than one Screen Test already, there’s one of Naomi Levine, a very early Warhol acolyte who seemed weirdly absent from Warhol’s filmed portraits — until now. Other recovered Screen Tests show figures who have yet to be recognized. (Hey, Boomers: If you know you once sat for Warhol’s camera, you might want to head to MoMA on Feb. 2, on the off chance of spotting your younger self.)

The newly processed rolls have also delivered fresh glimpses of the Pop life Warhol lived.

A roll from March 8, 1966, turned out to capture a classic Factory party. Another, shot in January of 1964 at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, whose roster Warhol was desperate to join, records the opening of a show by Frank Stella, a leader of the avant-garde that Warhol was anxious to enter. And the new footage of the Velvet Underground in their R.V. proves the Ann Arbor road trip to have been just as grungy as its riders have recollected.

Aschenbach’s efforts also recovered unused footage from Warhol films that have long been in circulation. From Warhol’s 5½ hour “Sleep,” we get nearly four new minutes of his boyfriend John Giorno, naked and sleeping. From the film titled “Couch,” we get several rolls of new debauchery — including some labeled “Jerry & Girl” — on that site of Warholian libertinism witnessed already on the known films. “Oh my God, the DNA on that couch would have a forensics specialist going crazy,” Trainor said jokingly. She guessed that maybe this additional footage, like some of the other newly processed rolls, remained undeveloped because of worries about legal issues around its explicit sex — in this case, shots of the Factory couch being used for an interracial threesome.

For Pierce, the explicit rolls were the most important find in the trove. There’d always been suggestions that Warhol was a “porn-oisseur,” as Pierce put it: In 1969, his “Blue Movie” was the first explicit film to get full theatrical release, and already in the 1950s he was turning out sprightly life drawings of men with their pants down or, sometimes, having sex. But hardly any explicit imagery had come to light from his Pop heyday in the ’60s.

Now, however, fully a quarter of the newly developed rolls show erotic action, from masturbation to fellatio. They might finally put to rest the undying myth that Warhol was asexual; they reveal how much further he was willing to go, in his frank account of human life, than any of his rivals in the Pop movement. More often than postwar America liked to let on, a tidy Campbell’s Soup supper might be followed by illicit adventures on the couch.

Pierce told me that he’s long wanted to write an essay on Warhol as a pornographer. With the fresh evidence in the new rolls, he has plenty of material.

Andy Warhol Exposed: Newly Processed Films From the 1960s

Feb. 2, 6:30 p.m., Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd Street, (212) 708-9400; moma.org.

The post Rediscovered Warhols That Warhol Never Saw appeared first on New York Times.