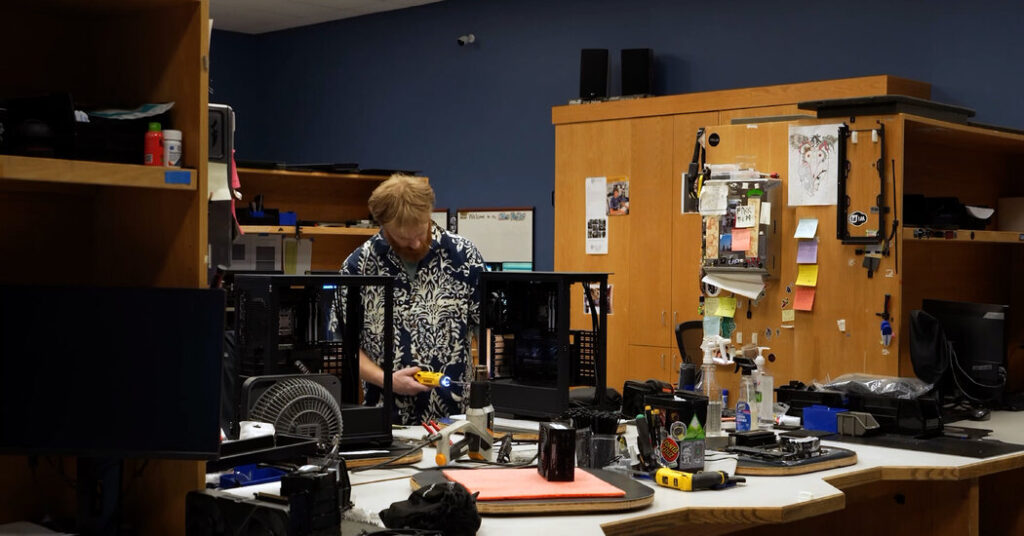

Kelt Reeves has sold high-end personal computers for 34 years, catering to gamers and others who are willing to pay $4,000 and more for extreme performance.

His company, Falcon Northwest, builds these systems to order using powerful computer chips, particularly a variety known as random-access memory, or RAM, which hold data temporarily while other chips crunch numbers and display graphics.

But as OpenAI, Meta, Google and other tech giants battle to win the artificial intelligence race, they have also demanded more memory chips for the data centers they are building to power the technology. Since late summer, Mr. Reeves has been grappling with a tripling of the cost of memory chips, pushing Falcon Northwest to raise the price of some of its popular high-end computers to more than $7,000 from about $5,800.

“This isn’t a consumer-driven bubble,” Mr. Reeves, 55, said. “Nobody is expecting this to be a quick blip that’s going to be over with.”

The crunch in memory chips is the latest domino effect from the A.I. frenzy, which has upended Silicon Valley and lifted the fortunes of A.I. chip makers like Nvidia. The boom has now gone beyond A.I. chips to reach other components used to build gadgets, which could ultimately affect the prices of mass-market personal computers and smartphones, too.

Memory chip manufacturers can make more money selling expensive chip varieties to A.I. data centers than to the PC and smartphone companies that had long driven their revenue. As the chip makers focus on producing more for A.I. customers, their shipments of consumer-grade chips have slowed and their prices have surged — costs that could eventually be passed on to consumers.

TechInsights, a market research firm, predicts that higher costs for memory chips would raise the price of a typical PC by $119, or 23 percent, by this fall from the same period last year. Besides RAM, those figures include price increases for the chips called NAND flash memory, which provide long-term storage in computers and phones.

“The memory market is bananas,” Mike Howard, an analyst at TechInsights, said at a recent tech conference. “It’s very difficult to find any sort of fast relief.”

On Wednesday, Amy Hood, Microsoft’s chief financial officer, said the company expects revenue from personal computers to decline “in part due to the potential impact on the PC market from increased memory pricing.”

Memory chips have long been considered a strategic commodity, an essential element in electronics that has prompted past trade wars between the United States and both Japan and South Korea.

Since memory chips are largely interchangeable, vendors for decades mainly competed on price. They often built too many factories and churned out too many chips, leading to plummeting prices and heavy losses.

Multiple makers dropped out, leaving South Korea’s Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix competing with Micron Technology, the sole U.S. supplier. (Some Chinese RAM makers have recently entered the market.) After many boom-bust cycles, Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron are now enjoying sustained sales growth, and their share prices have soared to record highs in the past year.

The demand is “almost exclusively from A.I.,” said Jim Handy, whose research firm, Objective Analysis, tracks the memory market.

The memory chip boom is also boosting the overall chip industry. The International Data Corporation, a research firm, projected that total chip industry revenues would jump 28 percent, to more than $1 trillion, this year, a milestone that many experts had not expected until 2030.

Micron, based in Boise, Idaho, is a microcosm for the changes. For 29 years, the company has sold different types of memory products to consumers and small businesses like Falcon Northwest.

But last month, Micron said it would discontinue that direct-to-consumer business, called Crucial, “to improve supply and support for our larger, strategic customers in faster-growing segments” such as A.I. chips.

Micron is also investing heavily in the factories that turn silicon wafers into chips. That includes building two new factories in Boise; buying an existing factory in Taiwan; and spending $100 billion on a project near Syracuse, N.Y., that is considered the state’s largest private investment.

The first of the new factories will not come online until mid-2027. In the meantime, Micron said, customers are receiving half to two-thirds of the memory they want to buy.

“Nobody is getting everything they want, and we regret that,” said Manish Bhatia, Micron’s executive vice president of global operations. “We’ve had to make some difficult calls.”

Furious demand from A.I. is not just for holding data in more computers. Memory is also playing a more strategic role, with new kinds of chips determining how fast applications like chatbots deliver answers.

“The memory appetite for A.I. is so much larger,” said Michael Stewart, a chip industry veteran who is a managing partner at the Microsoft venture capital fund M12. “It’s utterly different than all the computing we did before.”

The best example is what the industry calls high-bandwidth memory, or HBM, which is assembled by stacking RAM chips on top of one another rather than placing them side by side. Data moves vertically through layers of the stack instead of links along the edge of chips, a faster path.

Nvidia, which has been setting many hardware trends, buys huge volumes of HBM. The company bundles 12-high stacks of those chips inside the same package as its better-known A.I. processors, which allows faster data transfers than RAM placed elsewhere in a system.

This month, Nvidia described how a forthcoming microprocessor and an A.I. chip would use more and faster memory to achieve blazing speeds and lower costs per calculation.

“Because our demand is so high, every factory, every HBM supplier is gearing up,” Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief executive, said at the CES trade show in Las Vegas, adding that the world would need more chip factories.

This all means tough choices for consumers, particularly the hobbyists who assemble or upgrade their own PCs. A typical PC kit containing plug-in modules of RAM chips that sold for around $105 in early September was $250 at the end of December, according to the website PCPartPicker.

Apple, Dell and other big companies often strike long-term agreements with memory suppliers that tend to moderate big price swings. Even so, the average retail price of a standard-configuration laptop PC jumped 7 percent in the two weeks ending Jan. 3, according to Circana, a market research firm.

Among the PCs that experienced price increases were some Dell laptops. “Like others in the industry, Dell takes targeted pricing action, when necessary,” a company spokesman said, while declining to discuss specifics.

Apple and HP, the other big U.S. PC maker, declined to comment.

As for Mr. Reeves of Falcon Northwest, business is surprisingly good, even with the memory chip crunch.

His well-heeled customers, who are frequently devoted gamers, continue ordering PCs with lots of memory, he said, though the prices his company quotes them for the components change by the day. Falcon Northwest, which is in Medford, Ore., experienced a 30 percent revenue jump last year, he said.

Mr. Reeves said he feared less-established players in the PC supply chain would lose customers or find it hard to get the chips they needed. And people shopping for a low-priced PC may get an unpleasant surprise.

“I definitely feel for the budget buyer,” he said.

Tripp Mickle and Natallie Rocha contributed reporting.

The post How the A.I. Boom Could Push Up the Price of Your Next PC appeared first on New York Times.