The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the Federal Aviation Administration had approved dangerous flight routes that allowed an Army helicopter to fly into path of a passenger jet over the Potomac River on Jan. 29, 2025, to calamitous results.

The investigating board also castigated the agency for not doing enough to respond to warnings about longtime risks to safety and found a complacent culture within the air traffic control tower at Ronald Reagan National Airport that relied too heavily on pilots in the airspace being able to see and steer clear of each others’ aircraft, a practice called visual separation.

They also determined that insufficient warnings from the air traffic controller to the pilots of the Army Black Hawk helicopter and an American Airlines passenger jet involved in the crash, and altimeters that, unbeknown to the helicopter pilots, habitually gave faulty readings of altitude, also contributed to the tragic crash.

The long-awaited determination, which the board approved unanimously, is the culmination of a yearlong investigation that put the F.A.A. and Army under a microscope, as the board scrutinized how officials missed — or outright dismissed — risks that ultimately led to the collision.

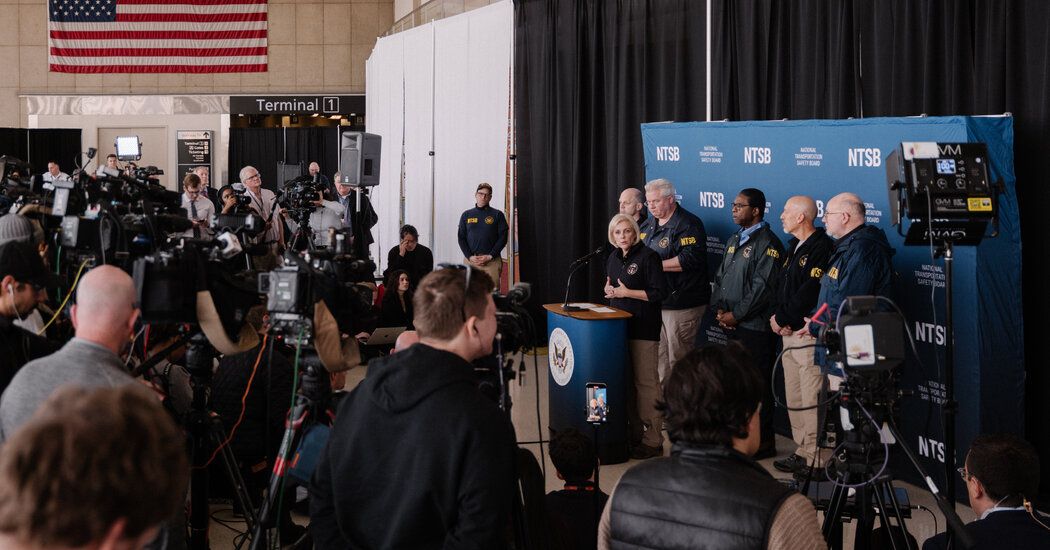

“It’s one failure after another,” Jennifer Homendy, the board chair, told reporters during a break in the proceedings, adding: “This was 100 percent preventable.”

The N.T.S.B. focused the brunt of its ire on the F.A.A., determining that the route the Army Black Hawk helicopter flew along the Potomac River and the landing path of American Airlines Flight 5342 were never designed to ensure separation between aircraft — and that the dangers posed by the crisscrossing paths were never adequately reviewed.

The board also determined that the F.A.A. ignored repeated appeals from controllers to reduce National Airport’s traffic, even as its main runway became the single busiest in the United States. That forced controllers to routinely divert planes to a backup runway, as they did with the American Airlines flight that night, to manage congestion.

“The F.A.A. values and appreciates the N.T.S.B’s expertise and input,” said Hannah Walden, a spokeswoman for the F.A.A., in a statement. The agency has worked with the N.T.S.B. throughout the investigation, she added, “acted immediately” to put into place its initial safety recommendations and “will carefully consider” the additional recommendations it made Tuesday.

Heavy flight traffic, investigators said, routinely led controllers at the airport to direct incoming planes to the backup runway, Runway 33, putting them in proximity with helicopters. It also led controllers to rely too much on pilots themselves to “see and avoid” each other, investigators determined, noting that the practice “introduced unacceptable risk” to the airspace.

N.T.S.B. staff members cited a culture within the F.A.A. that discouraged raising concerns about safety, describing how the agency installed, but never activated, a traffic management system that could have helped controllers handle traffic better on busy nights.

The board also concluded that the decision to put one controller in charge of both helicopter and airplane traffic on the night of the crash was not because of insufficient staffing in the tower — and that the duties should have been separated.

Notably, the board did not fault the pilots of either aircraft for failing to avoid each other. It did, however, determine that the pilots of the helicopter requested visual separation too early, and probably never had the correct commercial jet in their sights. The pilots of the jet, the board added, were too busy preparing for landing to note the approach of the helicopter, which the air traffic controller had not warned them about.

In a series of striking animated visual simulations, investigators strongly suggested that the instructor pilot in the helicopter, who was evaluating a less experienced pilot on a training flight, lost sight of the passenger jet as the two aircraft approached each other. The jet came back into his view only a second or two before impact, the video indicated.

Still, the N.T.S.B. determined that had the controller on duty noted the danger and explicitly warned pilots that they were at risk of colliding, they likely would have had time to avoid each other.

“They were not adequately prepared to do the jobs they were assigned to do,” said Brian Soper, who leads the N.T.S.B.’s air traffic control investigations.

Investigators also said that if either aircraft had been equipped with real-time tracking gear known as ADS-B In, the pilots might have been alerted nearly a minute before the collision of the danger, giving them ample time to avoid each other.

Yet the board also found that the helicopter pilots’ reliance on other equipment contributed significantly to the crash. Investigators concluded that the pilots of the Army helicopter probably thought they were flying about 100 feet lower than their actual altitude because of idiosyncrasies in the readings of altimeters on the Black Hawks that the Army knew about but never informed aviators of.

“They wouldn’t know it,” said Capt. Van McKenny, a helicopter investigator with the N.T.S.B. “It’s not in their manual, it’s not in the training.”

The Army also never realized that the barometric altimeters in their helicopters were giving pilots a false sense of their flying height because the service didn’t routinely collect the relevant data. Instead, the Army relied on a voluntary reporting system that was seldom used.

The F.A.A., investigators said, had plenty of data about the dangers to the Washington airspace, however, that the agency simply ignored.

The N.T.S.B. questioned why on multiple occasions, the F.A.A. relaxed the restrictions on when a single controller could be assigned to manage helicopter and airplane traffic simultaneously, creating a culture of complacency that things would work out, even when controllers became overwhelmed.

And the board excoriated the F.A.A. for downgrading National Airport’s facility rating in 2018, a measure that determines the experience level required for controllers to work there. That change, and its commensurate pay cut, made it more difficult for the tower to attract experienced personnel capable of handling Washington’s busy airspace, the N.T.S.B. staff said, especially given the city’s high cost of living.

“This tower is essentially treated as a training facility,” Ms. Homendy said. “It is a pass-through, they can’t attract people here, which is a problem.”

In total, the N.T.S.B. issued over 70 findings about the midair collision, and approved dozens of recommendations aimed at preventing similar crashes. The Trump administration and Congress will determine whether to put them into place.

The F.A.A. has already limited what aircraft can fly through the airspace surrounding National Airport. It has also reconfigured helicopter routes in the area, in response to urgent recommendations that the N.T.S.B. issued last March, and it rolled out a redesign plan it says will streamline safety monitoring.

The agency also has been making significant investments to modernize the country’s aging air traffic control system. A funding bill pending before the Senate would pump billions more dollars into the F.A.A. to help with hiring more controllers, but the legislation could falter amid a political standoff over funding for immigration enforcement.

The N.T.S.B. plans to publish a full report detailing the findings, causes and recommendations stemming from the crash in the weeks after Tuesday’s meeting.

Karoun Demirjian is a breaking news reporter for The Times.

The post Safety Board Blames F.A.A. For Multiple Failures in D.C. Crash appeared first on New York Times.