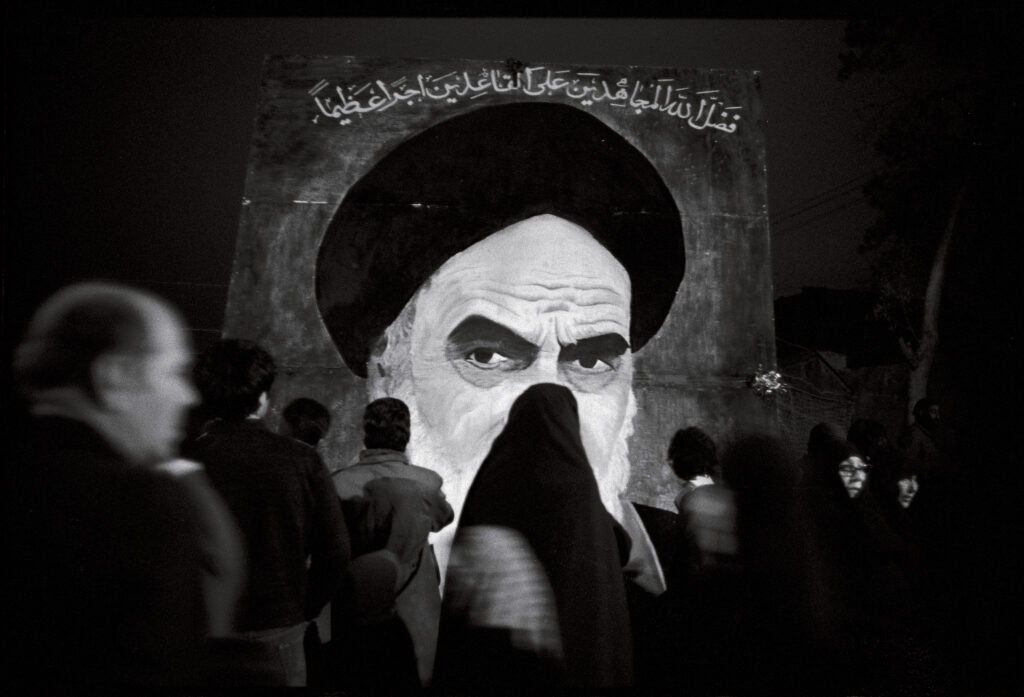

David Burnett is a photojournalist based in New York. The photos with this column were published in his book “44 Days: Iran and the Remaking of the World.”

Iran has come full circle. The protesters of the revolution have become the regime. But the street terror is the same.

During the revolution, long before the internet and cellphones, demonstrators and the military alike relied on telephones and the occasional radio to spread word amid the chaos. In the 2020s, word of a protest can spread instantly — unless the internet is cut and the cell network has been shut down.

Arriving in Tehran just after Christmas of 1978, I made my way to the Inter-Continental Hotel, where I’d been told the foreign press was staying, primarily because the phone lines there were reliable. After a quick check-in, I took a cab to the Associated Press office, which was an expanded family room in the home of bureau chief Parviz Raein, who was also the Time stringer. His home served as a nerve center for the city, with informants all over town using payphones to make reports and forward messages.

The phone rang, and following a short, clipped conversation, Raein announced, “There is gunfire in Esfand Square.” AP photographer Bob Dear scrambled into action. I grabbed my bag and joined Dear in a car with a driver, and we drove for 15 minutes to the edge of a big demonstration.

There, the crowd was being met by police and troops. I couldn’t understand most of the chants, but it didn’t take long to pick up that “Marg bar Shah” meant “Death to the Shah” and that “Marg bar America” was “death to America.” Yet the crowds were almost uniformly happy to see someone with a camera recording what was happening.

Million-strong gatherings made a low rumble from the area of the Shahyad monument, where mullahs would often speak for hours. Tense moments could result in troops or police shooting into a crowd, producing what became a long list of martyrs to the revolution. Groups of young protesters sometimes could be seen running from the authorities, which was a dangerous thing to do. The day before Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s return from exile in Paris, students taunted a truckload of Imperial Guard personnel, and one of them responded with rifle fire, killing a demonstrator. Friends of the dead man paraded through a park showing hands dipped in the blood of their fallen comrade.

Western journalists can no longer work freely in Iran, but the regime’s media control and communications blackout has not succeeded in keeping images of today’s protests from reaching the world. These leave no doubt that the current regime has been even more ruthless in its treatment of demonstrators. The U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency reported Tuesday that at least 6,159 people have been killed, with many more feared dead. What we have glimpsed from the Tehran’s streets, and morgues, shows a frightening brutality beyond what I witnessed in 1979.

In 1979, Tehran crackled with a sense that Iran stood on the cusp of change — that a new path had appeared from which there would be no going back. Now, almost a half-century later, a volatile and angry country ponders where things go from here. The revolutionaries have turned gray, but judging by the deadly serious way they are reacting to the uprising of a new generation, I imagine they still recognize the approach of change when they see it.

The post I saw the birth of the Islamic Republic. Its dying days are even bloodier. appeared first on Washington Post.