A federal immigration judge on Wednesday granted asylum to a Chinese dissident who had taken great risks to secretly record his country’s mass detention and surveillance of Uyghurs.

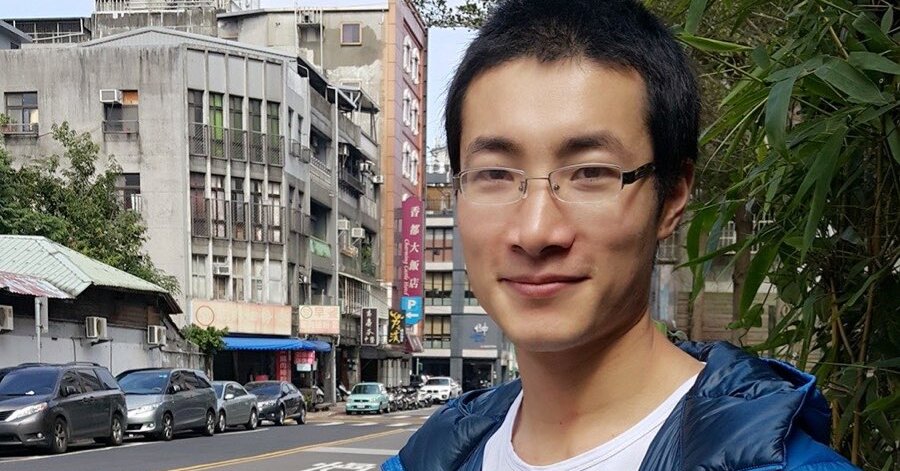

Heng Guan, 38, was detained last August in upstate New York, and supporters feared that he would be sent back to China, where human rights activists said he would almost certainly face persecution.

After an outcry from human rights advocates, Democrats and The Wall Street Journal editorial page, the Trump administration sought to deport him instead to Uganda.

Then in late December, the administration dropped that request, but Mr. Guan has remained in immigration detention.

The judge, Charles M. Ouslander, said that Mr. Guan’s testimony was “credible and worthy of belief.” Judge Ouslander referred to a number of factors, including the State Department’s previous designation of China’s treatment of the Uyghurs in its far western region of Xinjiang as a “genocide.”

He also noted a letter submitted to the court by the State Department that described Mr. Guan’s role in documenting the Chinese government’s abuses.

Niles Gerry, a lawyer for the Department of Homeland Security, suggested during the hearing that the department could appeal the decision. The department has 30 days to do that, during which time Mr. Guan will remain in detention.

The decision is a rare defeat for the Trump administration’s hardline immigration effort. Winning asylum cases is now exceedingly difficult.

But Mr. Guan had what appeared to be a strong claim, according to his supporters.

In 2020, while he was living in China, he traveled to Xinjiang and secretly shot video of detention centers that held mostly Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic group. The centers were part of a draconian campaign under the Chinese leader Xi Jinping to indoctrinate Uyghurs and root out what the Communist Party said were dangerous ideas fueling resistance and extremist violence.

In 2021, Mr. Guan fled China, traveling through Ecuador before sailing on a small inflatable boat from the Bahamas to Florida. While he was on the water, Mr. Guan released the footage, which documented hulking detention camps, detailing their high walls, guard towers and barbed wire.

Trump Administration: Live Updates

Updated

- U.S. allies in the Middle East have been pressing for weeks to prevent a conflict with Iran.

- F.B.I. agents search an election center in Georgia over the 2020 election.

- President Trump threatened Iran with a ‘massive Armada’ and pressed a set of demands.

It became rare visual evidence of the scale and brutality of China’s clampdown on the Uyghurs and refuted Beijing’s claims that people lived at the centers voluntarily.

In previous years, the Uyghur issue had become a major flashpoint in the relationship between the Trump administration and Beijing. And on the last full day of Mr. Trump’s first term, the State Department officially declared the Chinese government’s actions in Xinjiang a “genocide.”

Mr. Guan’s “compelling firsthand documentation added significant weight to the Trump administration’s own findings that the atrocities amounted to genocide,” said Rayhan Asat, a human rights lawyer at the Atlantic Council, a nonprofit that promotes international engagement. Ms. Asat’s brother has been imprisoned in Xinjiang since 2016.

After releasing the videos, Mr. Guan applied for asylum, joining the queue of more than three million people waiting for their case to wend through the overburdened court system. He had just moved to upstate New York when he was detained last summer after he was caught up in an immigration enforcement effort targeting his housemates.

In a telephone interview before his release, Mr. Guan said he gave the immigration agents his documents and told them that he had applied for asylum and had a permit to work legally in the United States. But, he said, the agents didn’t seem interested.

“Their focus was mainly on how I arrived in the United States,” Mr. Guan recalled. “So I told them the truth.”

Mr. Guan feared that he might be sent back to China. His mother, Luo Yun, who lives in Taiwan, has said that after the Xinjiang footage was released, even distant members of Mr. Guan’s family in China were questioned by Chinese police officers.

Mr. Guan’s concerns were hardly allayed in December when the Trump administration sought instead for his deportation to Uganda, which has close political and economic ties with Beijing. “It felt very unreasonable,” he said.

Days later, the Department of Homeland Security issued a directive that limited deportation to Uganda to immigrants from most other African nations. The deportation request for Mr. Guan was promptly withdrawn.

Despite the monthslong ordeal, Mr. Guan said that he did not regret his decision to flee to the United States. He said he understood why, after years of rising illegal migration, Mr. Trump was taking such a hard line. National immigration policies often fluctuated, he reasoned, and he happened to come at a time of tightening. “I’m just a little unlucky, that’s all,” he said.

America, he said, was a country that followed laws. Not long after he landed on a Florida beach in his boat, he had watched from afar as a car came to a stop at an intersection. “There was no one else around, no cars, no people, and yet this driver was still following the rules,” he recalled. “That left a deep impression on me.”

Mr. Guan said that the long days in detention had given him ample time to reflect, and he wanted to make a big life change. He had been more of a lone wolf, preferring to keep to himself. But while in the correctional facility, he struck up a friendship with other detainees, including an immigrant from Cameroon who helped pull him out of an especially difficult period emotionally.

It made Mr. Guan realize the value of human connection.

“I would like to help other people,” he said. “And maybe that can also help enrich my own life, too.”

Amy Qin writes about Asian American communities for The Times.

The post Dissident Who Daringly Documented Uyghurs’ Repression Wins Asylum appeared first on New York Times.