Just before 8am one day last April, an office manager who went by the name Amani sent out a motivational message to his colleagues and subordinates. “Every day brings a new opportunity—a chance to connect, to inspire, and to make a difference,” he wrote in his 500-word post to an office-wide WhatsApp group. “Talk to that next customer like you’re bringing them something valuable—because you are.”

Amani wasn’t rallying a typical corporate sales team. He and his underlings worked inside a “pig butchering” compound, a criminal operation built to carry out scams—promising romance and riches from crypto investments—that often defraud victims out of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars at a time.

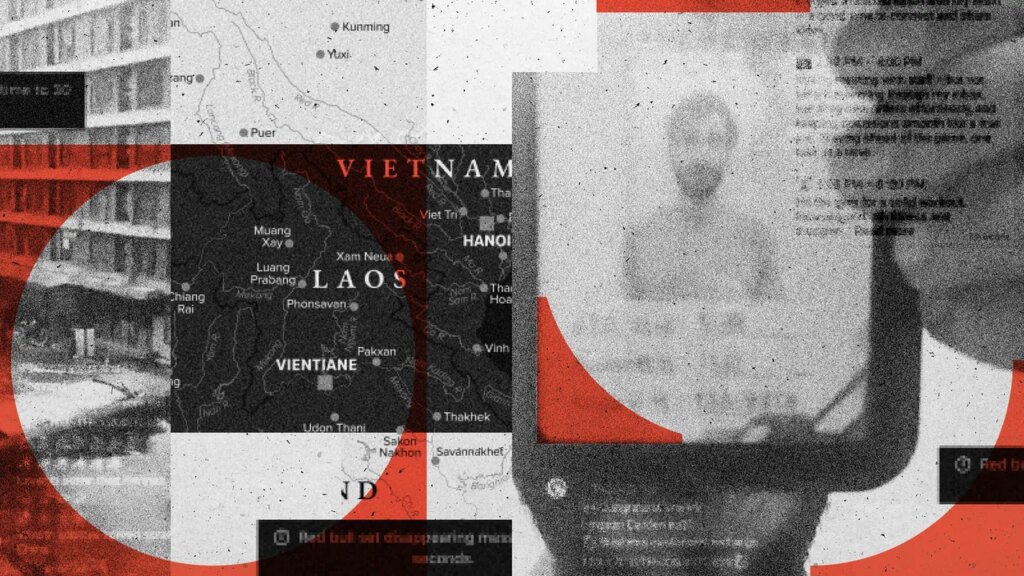

He Leaked the Secrets of a Southeast Asian Scam Compound. Then He Had to Get Out Alive

He Leaked the Secrets of a Southeast Asian Scam Compound. Then He Had to Get Out Alive

Read the full story of WIRED’s source, Mohammad Muzahir, here.

The workers Amani was addressing were eight hours into their 15-hour night shift in a high-rise building in the Golden Triangle special economic zone in Northern Laos. Like their marks, most of them were victims, too: forced laborers trapped in the compound, held in debt bondage with no passports. They struggled to meet scam revenue quotas to avoid fines that deepened their debt. Anyone who broke rules or attempted to escape faced far worse consequences: beatings, torture, even death.

The bizarre reality of daily life in a Southeast Asian scam compound—the tactics, the tone, the mix of cruelty and upbeat corporate prattle—is revealed at an unprecedented level of resolution in a leak of documents to WIRED from a whistleblower inside one such sprawling fraud operation. The facility, known as the Boshang compound, is one of dozens of scam operations across Southeast Asia that have enslaved hundreds of thousands of people. Often lured from the poorest regions of Asia and Africa with fake job offers, these conscripts have become engines of the most lucrative form of cybercrime in the world, coerced into stealing tens of billions of dollars.

Last June, one of those forced laborers, an Indian man named Mohammad Muzahir, contacted WIRED while he was still captive inside the scam compound that had trapped him. Over the following weeks, Muzahir, who initially identified himself only as “Red Bull,” shared with WIRED a trove of information about the scam operation. His leaks included internal documents, scam scripts, training guides, operational flowcharts, and photographs and videos from inside the compound.

Of all Muzahir’s leaks, the most revealing is a collection of screen recordings in which he scrolled through three months’ worth of the compound’s internal WhatsApp group chats. Those videos, which WIRED converted into 4,200 pages of screenshots, capture hour-by-hour conversations between the compound’s workers and their bosses—and the nightmare workplace culture of a pig butchering organization.

“It’s a slave colony that’s trying to pretend it’s a company,” says Erin West, a former Santa Clara County, California, prosecutor who leads an anti-scam organization called Operation Shamrock and who reviewed the chat logs obtained by WIRED. Another researcher who reviewed the leaked chat logs, Jacob Sims of Harvard University’s Asia Center, also remarked on their “Orwellian veneer of legitimacy.”

“It’s terrifying, because it’s manipulation and coercion,” says Sims, who studies Southeast Asian scam compounds. “Combining those two things together motivates people the most. And it’s one of the key reasons why these compounds are so profitable.”

In another chat message, sent within hours of Amani’s saccharine pep talk, a higher-level boss weighed in: “Don’t resist the company’s rules and regulations,” he wrote. “Otherwise you can’t survive here.” The staffers responded with 26 emoji reactions, all thumbs-ups and salutes.

Fined Into Slavery

In total, according to WIRED’s analysis of the group chat, more than 30 of the compound’s workers successfully defrauded at least one victim in the 11 weeks of records available, totaling to around $2.2 million in stolen funds. Yet the bosses in the chat frequently voiced their disappointment in the group’s performance, berated the staff for lack of effort, and imposed fine after fine.

Rather than explicit imprisonment, the compound relied on a system of indentured servitude and debt to control its workers. As Muzahir described it, he was paid a base salary of 3,500 Chinese yuan a month (about $500), which in theory entailed 75 hours a week of night shifts including breaks to eat. Although his passport had been taken from him, he was told that if he could pay off his “contract” with a $5,400 payment, it would be returned to him and he would be allowed to leave.

In reality, the WhatsApp chats reveal how even that meager salary was almost entirely chipped away with fines. One message warns that anyone who fails to start a “first chat”—an introductory conversation with a scam victim—on any given day will be fined 50 yuan, and the failure will be announced to the group. Filing a false progress report results in a fine of 1,000 yuan. Falling asleep in the office, or “watching unrelated video, chatting with friends, and any activity that is not related to the job” are each punishable with a 200 yuan fine, as is any “disturbance” in the dormitory, where workers sleep five or six to a room in bunk beds.

One message notes a fine of 500 yuan for a worker who slept late, and another fined 200 yuan for not being in the dorm at “check-in time” following his shift. Resist a fine by not signing a form that admits to the misbehavior, and the fine is doubled.

Muzahir himself described being fined so much that he was virtually broke. The food in the office cafeteria was also frequently denied as a punishment, the messages showed, with workers’ ID badges that granted access to the canteen sometimes being taken away for seven days for small infractions like tardiness. Even the freedom to bring in snacks and drinks—other than betel nuts, a stimulant—could be rescinded if staff underperformed. Time off was also withheld, with staff sometimes forced to work seven nights a week, Muzahir says.

Yet those punishments could be avoided, the bosses frequently promised, if they successfully scammed someone—or “opened a customer,” as the bosses euphemistically described scamming a new victim. (Scamming the same victim multiple times was called a “recharge.”) In theory, workers were entitled to a commission, over and above their salary, for any scams they pulled off. Muzahir says he successfully perpetrated two scams during his months in the compound—both of which left him racked with regret, he says—and he was never paid after either of them.

Bosses nonetheless used workers’ illusory hope of paying off their debt—or even going home rich—as a motivator. “I understand—when penalties or fines come your way, it’s easy to feel disheartened. But I urge you not to see it as a punishment, but as a lesson and an investment in your own growth,” wrote Amani. “Don’t fear the fine. Let it fuel your fire.”

The more senior boss, who went by the name Da Hai, spelled out the carrot-and-stick approach more clearly. “The company’s incentives are much higher than the fines, so as long as you work hard to open new customers you will receive a generous reward!” he wrote.

One of the bosses’ tactics was to play teams off one another, reprimanding underperforming workers while pointing to the success of other scammers in the compound. Each room of the office appears to have had a Chinese ceremonial drum, played when a worker successfully scammed a victim for a six-figure sum. “Do you know why the next office is beating drums?” wrote a higher-level boss called Alang.

A victim had paid “480k,” a boss who goes by the name Libo answers.

“It doesn’t matter, because he belongs to others,” Alang responds. “The important thing is, which one of you can play the drum?”

Under the Pretense, a Brutal Reality

Beyond these manipulative tactics, the messages occasionally offer glimpses of a far harsher reality—as does the personal experience and testimony of Muzahir himself. Muzahir describes hearing stories of people who were tortured and says he was himself threatened by Amani with beating and electrocution if he didn’t find new “clients.” Sometimes coworkers disappeared without explanation.

Eventually Muzahir came up with a plan to trick his captors into letting him leave. When the bosses caught on, he was held in a room, beaten, slapped and kicked, denied food and water, and made to drink a solution with a white powder dissolved in it, which seems to have been intended to make him more cooperative with their interrogation.

Occasional messages in the chat logs hint that these cruel punishments lurked underneath the compound’s motivational messages. At one point, the boss Alang mentions a girl who “sneaked away from the company and went to work in a brothel,” and another person in the group mentions that the “company” still holds her passport. Among the captive workers, Muzahir says, rumor had it that the girl was in fact sold into prostitution, a practice documented in other accounts from scam compound survivors.

At another point, while chastising the group for underperformance, the boss Da Hai hints at the large sum of money workers needed to produce if they ever hoped to leave the compound. “You continue to violate the company’s regulations,” he writes to the group. “If you continue like this, please prepare your compensation and get out of here.”

Such references to paying “compensation” for release are in fact “coded words for ransom and debt bondage,” says Harvard’s Sims. The nation of Laos, Sims points out, is a signatory to the Palermo Protocol, which classifies anyone held in debt and forced to work without freedom of movement a victim of human trafficking. “There is no gray area here.”

A Day in the Life of a Scammer

The leaked WhatsApp chats include a message from a boss who went by the name Terry laying out a strict work schedule for those under his supervision. “Obey and respect the working time,” the message says. Each shift would start at around 11:30 pm Beijing time—10:30 pm in Laos—with people told to arrive a few minutes early. Before the day ended at 2 pm Beijing time, there would be two break periods, one of which was set aside for meals. By 5 pm everyone was required to be back in their dormitories and “sleep or keep silence, no disturbing the others.” If the rules weren’t followed, fines would be issued and ID badges could be taken away.

The reason for this nocturnal schedule was to sync with the waking hours of victims in the US—almost entirely Indian-American men. (It’s a common practice to pair scammers with victims of their own ethnicity, to avoid language and culture barriers.)

In grim contrast to their actual lives, all staffers were required to post an imaginary daily schedule for their fake personas—the wealthy, attractive women they’d pretend to be during scams. In hour-by-hour breakdowns, they describe mornings spent meditating, practicing yoga, taking walks, and “setting positive intentions” for the day. Other activities include a “relaxed” lunch with their team, dinner with loved ones, and time at the gym—when in reality they were spending entire nights in front of a screen in a fluorescent-lit office space.

Many of the staffers writing the schedules were nonetheless admonished for not sticking to the script while scamming. “The purpose of editing a daily plan is to let everyone know clearly what you are going to share with your clients today when you start working,” one boss complained. “I find that many people just do it to get the job done and don’t apply your plan to your clients.”

During each day’s work, the forced scammers were also required—under the threat of more fines—to report their scamming efforts back to the bosses in detail. The WhatsApp logs are filled with lengthy messages from every team member that offer those reports in identical message templates, listing their “team,” their name, and their recent online activity with the fake profiles. They would report how many active social media accounts they were operating, if any of their accounts were suspended, how many chats they’d started, how many were ongoing, any successful scams, and their target for the month. The internal chats also show scammers sharing with bosses and colleagues screenshots of their victim chats on Facebook Messenger, Instagram, Snapchat, and other chat apps, while asking questions about potential victims.

Bosses frequently gave pointed feedback about how workers were managing the meta-narrative of their scams. “When sharing travel topics, you need to know how to share details,” one chat says. Another message from a boss admonishes workers not to mention the car their persona drives if they can’t provide a convincing photo of it.

Managers would keep a close eye on the activity. On multiple occasions, bosses ask the forced workers to connect their WhatsApp accounts to the managers’ computers so they could monitor the conversations themselves.

Anatomy of a Scam

The 25 scripts and guides Muzahir shared with WIRED, too, offer a window into the tactics and training of the compound’s workers. Many of the guidance documents pertain to the nitty gritty of carrying out cryptocurrency investment scams, including how to build a friendship that can segue into an investment proposition, how to explain what cryptocurrency is, and what to do once a target agrees to make an investment.

One document lists “100 chat topics,” geared toward building the emotional intimacy required for a romance scam (“What was your dream when you were little?” “What was the last time I cried for?”). Another suggests providing an update about having gotten into a car accident. “On my way to work in the morning, my car was hit by a car following at a traffic light, which almost delayed my meeting in the morning. Thank you for your concern. I am fine.”

Multiple documents guide scammers to pretend they are currently making an investment, then introduce the idea that banks are resistant to letting their customers convert their money into cryptocurrency. “If we transfer or withdraw funds, they will have one less customer,” one proposed scam script says. “If everyone does this, then the bank will be in crisis and there will be a situation of capital rupture. I can understand their motives, but as a bank customer, I should not be hindered from transferring assets reasonably and legally. This is what makes me angry.”

The documents also display a technique that researchers say is often used in Southeast Asian investment and romance scams: Attackers intentionally mention the concept of scams—even directly talking about the threat of investment scams—as a way of inoculating themselves against suspicion. The idea is that if a person is willing to talk openly about scams and isn’t avoiding the subject or acting strange about it, then they couldn’t be a scammer themself.

That strategy goes so far as to include mentally preparing a victim for the anti-fraud warnings from their bank or even law enforcement that they may have to ignore in order to transfer large amounts of fiat currency into cryptocurrency. “I was going to transfer funds to my coinbase today, but I was deliberately delayed and obstructed by the bank staff,” one script reads, referring to the popular crypto wallet service Coinbase. “I also received an anti-fraud call from the FBI today, which wasted a lot of my time.”

The materials Muzahir provided from the Boshang compound also document the key role generative AI tools play in its deceptions. Muzahir described to WIRED how the compound workers are trained in using tools like ChatGPT and Deepseek to come up with responses in chats with victims and craft natural-sounding turns of phrase. But even more crucial was the compound’s use of deepfake AI software to allow scammers to convincingly video chat with victims at their request using an AI-generated face, impersonating an individual whose photos they’ve stolen for a fake persona.

The internal chat logs Muzahir captured describe a dedicated “AI room” where a female model conducts face-swapped calls on request with an endless parade of victims. One WhatsApp message from a boss to the group chat notes that “Sana (our model who helps us to call) is not available tonight. she is not feeling well. Therefore, don’t promise your customers to call them. Maybe she will come at work in the morning. Plan your work accordin[g]ly.”

Other chats about the AI room relate to scheduling challenges given demand for face-swapped calls and the fact that a single model can only do one deepfake call at a time. One chat, for example, notes: “If there is a ‘busy’ sign on her door, change it to ‘free’ when you come out, so as to avoid crowding and frequent door openings.”

The scripts Muzahir shared also include tips for delaying a video chat with a victim—perhaps until the scammer is prepared to use deepfake tools. “When we meet, it will not be awkward but rather we will look forward to it,” says one script about what to say when a victim asks to video chat. It continues, “We are strengthening our relationship every day. You have also seen my photos. When we meet, can you recognize me?”

Beyond the Golden Triangle

As dystopian as the Golden Triangle compound described in the leaked documents may be, its work environment appears to have been relatively lax compared to other compounds in countries like Cambodia or Myanmar. In those facilities, Operation Shamrock’s Erin West says, she has heard firsthand stories of workers being beaten simply for missing their quota of scams or being forced to work 18-hour shifts while standing, with none of the pretense of voluntary work in a corporate environment.

The relative leniency of Muzahir’s compound, says Harvard’s Sims, likely stems from scam operations’ sense of total control in Laos’ Golden Triangle region—a zone of the country controlled largely by Chinese business interests that has become a host to crimes ranging from narcotics and organ sales to illegal wildlife trafficking. Even human trafficking victims who escape from a compound there, Sims points out, can be tracked down relatively easily thanks to Chinese organized crime’s influence over local law enforcement. “These guys don’t have to be held in a cell,” Sims says. “The whole place is a closed circuit.”

Nonetheless, the Boshang compound that held Muzahir appears to have moved in November from the Golden Triangle to Cambodia, a country that’s become by some measures an even safer base for scammers to operate from. Based on messages from his former coworkers, Muzahir says he’s determined that the operation and its captive workers are now based in the town of Chrey Thom, what Sims and West both describe as a growing hot spot for scam operations.

The move may have been precipitated, Sims speculates, by police raids on compounds across the region around that time. Many of those raids appear to have been part of a “performative crackdown,” as Sims puts it. (One such raid in June targeted the building where Muzahir’s compound had previously been located, but Muzahir says the workers who were rounded up by police were quickly released again and returned to work.)

Nonetheless, the nuisance of even those superficial disruptions may have persuaded the operation’s bosses to relocate to Cambodia. In that country, even the family of the country’s prime minister, Hun Manet, has been linked to a corporate conglomerate that oversees a subsidiary with documented ties to the burgeoning scam industry. “It’s been a very hospitable environment to do this work,” West says.

One of Muzahir’s old bosses also confirmed to him in a private text exchange that the compound is still “recruiting” new workers—victims trapped in a system of modern slavery hidden under a thin facade of a willing workplace.

“This is a place to work, not to enjoy,” that same boss had written in the group chat during Muzahir’s time in the compound, in a rare moment when the mask of a normal office environment seemed to slip. “You can only enjoy life when you leave here.”

Additional reporting by Sophia Takla, Maddy Varner, and Zeyi Yang.

Let us know what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor at [email protected].

The post Revealed: Leaked Chats Expose the Daily Life of a Scam Compound’s Enslaved Workforce appeared first on Wired.