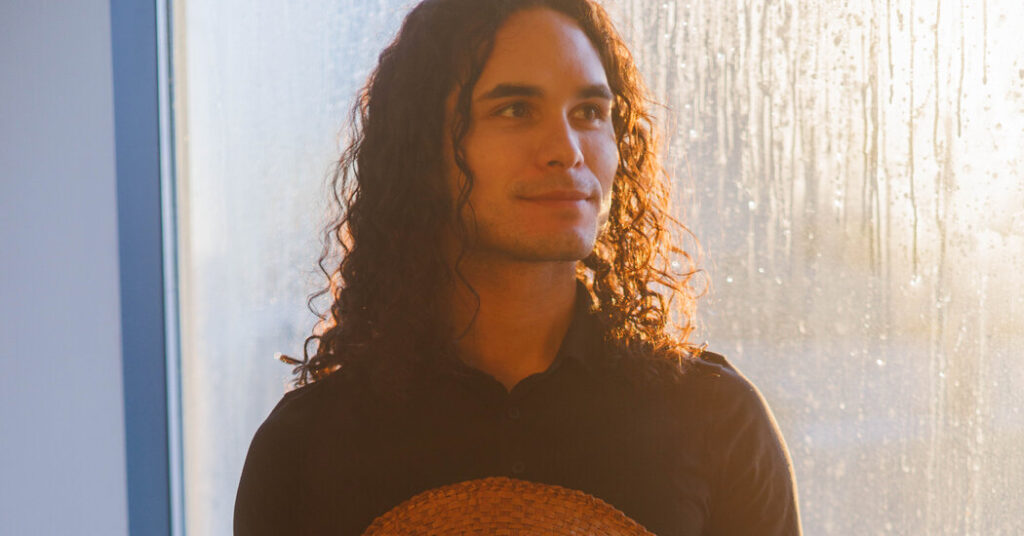

As a child, Cameron Fraser-Monroe was haunted by the legend of an evil woodsman who snatched children after dark, recounted by elders in his community, the Tla’amin Nation of British Columbia’s northern Sunshine Coast.

Fast forward two decades and Fraser-Monroe, now a choreographer, has transformed that fear into a ballet that touches on deep-seated divisions in Canada.

“T’el: The Wild Man of the Woods,” at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, is the first full-length work by an Indigenous choreographer to be commissioned by a major company. It’s part of an effort by the Royal Winnipeg, Canada’s oldest professional ballet company, to foster meaningful reconciliation with the country’s Indigenous people — echoing a broader national goal that has been pursued for decades.

Neither process has been smooth. Change has been slow at the political level. And the ballet company, which has programmed Indigenous artists and creations for more than 10 years, has faced unexpected resistance. Last February, all four members of the company’s Indigenous Advisory Circle resigned, saying they felt tokenized and disregarded.

None of this has tempered Fraser-Monroe’s enthusiasm about taking “T’el” on a two-week tour of British Columbia. The first stop, on Jan. 27 in Powell River, a city on the traditional territory of the Tla’amin people, is especially meaningful: His aunties and grandmother will be in the audience.

“I will be bringing this ballet back to the place where the story was kept,” Fraser-Monroe said in a Zoom interview from Montreal, days before flying to Winnipeg to begin rehearsals. “It’s affirming for the elders in Tla’amin. And, for the kids, this might be the first ballet they’ve seen.”

“T’el,” which premiered in Winnipeg in 2024, conflates styles and sounds. It begins in darkness, the pounding of powwow drums cutting to chanting and cello chords. Dressed in shades of cedar, the dancers move in solemn synchronization, their sweeping arms and expressive upper bodies punctuated by moments of stillness. The music can sound orchestral one minute and electronic the next, as the composer and cellist Cris Derksen loops sequences of classical melody with her set of pedals.

A graduate of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School, Fraser-Monroe trained in a number of dance forms, including traditional Indigenous grass and hoop dancing. But when he became a choreographer, he chose ballet as his vocabulary, hoping to reach the widest possible audience. “Ballet is familiar,” he said. “It’s the lure that lets me tell a very old story in a new format.”

Ballet and Indigenous culture may not seem like an intuitive pairing. Ballet is a product of the European empires that colonized North America and displaced First Nations tribes and their cultures. Today, there remains a major disconnect between the art form and Indigenous communities, with First Nations dancers exceedingly rare in ballet companies. At the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, there are no Indigenous dancers, despite the city having the largest urban Indigenous population in Canada, with 12.4 percent identifying as First Nations, Inuit or Métis.

The Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s production has an all-Indigenous creative team: Derkson is Cree and Asa Benally, the costume designer, a member of the Navajo nation.

“I use my platform to elevate Indigenous artists,” Fraser-Monroe said. “My grandpa would always say that we rise together, and I take that very seriously.”

But because Fraser-Monroe will not cast non-Indigenous dancers in Indigenous roles, he needed to do some creative troubleshooting for “T’el.” His solution was to set the fable in a fictional neighborhood, developing characters organically with the dancers in the studio.

“I’m looking to represent a community made up of the artists in the room, as opposed to my specific community,” he said. “I don’t want to ask the dancers to step into lived experience they don’t have access to.”

Kyra Soo, a corps de ballet dancer, reflected on the choreographer’s approach: “Cameron trusts us with something that’s not native to us, but very important to him. We all feel the responsibility of that.”

In rehearsal, Fraser-Monroe has developed a method to balance working with two distinct traditions. When incorporating a specific sequence of Tla’amin movement, he takes his time and works intentionally. “It’s very important that I share the steps the way they were shared with me,” he said, “talking about their oral history, where they came from and their purpose.”

When choreographing a section that’s explicitly classical or contemporary, he allows for more experimentation. “Cameron is very collaborative,” Soo said. “He generally starts with an idea then lets it flow, looking around the room to see what’s happening.”

The Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s interest in Indigenous programming dates back 50 years. In 1971, Norbert Vesak choreographed an adaptation of George Ryga’s play “The Ecstasy of Rita Joe,” (1967), a seminal work about Canada’s treatment of First Nations people. (Neither Vesak or Ryga are Indigenous.)

A more ambitious project began in 2014 in conjunction with Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which spent years documenting the harm caused by the country’s Indian Residential Schools, a system that operated for more than 150 years. In addition to calls to action, the commission wanted to turn its findings into something that would resonate with Canadians — new works of art exploring what reconciliation means. Since then, federal funding has been directed to arts organizations keen on creating this work.

Those funds helped support the Royal Winnipeg’s “Going Home Star,” a full-length ballet about a young man’s experience in a residential school. Non-Indigenous dancers were cast in Indigenous roles, something that would seem unthinkable in a contemporary movie or play. But the production was largely well received when it toured Canada in 2016. Publicly, few took issue with the casting, and the convention bending required to make the concept work.

While Fraser-Monroe found it necessary to invite a workaround when it came to casting “T’el,” he wanted to honor the fable’s provenance as an oral history. He asked the Tla’amin community’s oldest living knowledge keeper, the elder Elsie Paul, 94, to narrate the ballet in both English and Ayajuthem, the nation’s traditional language. A residential-school survivor, Paul is one of the few remaining fluent speakers of Ayajuthem. At critical plot points, audiences hear her recorded voice recounting the narrative.

“T’el” has opened doors for both Fraser-Monroe and the ballet company. After its premiere in 2024, New York City Center asked Fraser-Monroe to create a new work for its Fall for Dance festival, the first time in almost 50 years that the Royal Winnipeg Ballet had been invited to perform in New York City.

But it was just a few months later that the company’s Indigenous Advisory Circle, which had formed in 2018, resigned en masse. The Anishinaabe lawyer Danielle Morrison, a founding member of the advisory group, told the CBC at the time that they had repeatedly asked the ballet’s leadership for board representation, which was never granted. “We were not seen as equals,” she said.

Albert McLeod, an elder and another member of the circle, said he was optimistic when “T’el” was commissioned and enjoyed the ballet’s premiere. But when no communication was established between the circle and the board, he lost faith.

“Our names were in every program,” McLeod said from his home in Winnipeg. “The company was really trying to signal to the public and their funders that they were following this whole idea of decolonization and reconciliation. They weren’t. We were just dressing.”

Tara Letwiniuk, a lawyer, was both a member of the circle and the board of directors, but she held the board position in a personal capacity, with no mandated authority to represent the circle.

The situation hit a boiling point last February when the board announced the appointment of Christopher Stowell as the company’s new artistic director, a decision the circle felt they should have been consulted on. The company has since issued an apology and hired a third-party consulting firm to review what happened, though Morrison said in a recent email that the process had stalled and the company had become uncommunicative.

The board’s new chairman, Ernest Cholakis, said in an email that he was unable to speak about the matter before the consulting firm’s report is made public.

Stowell said he was saddened and dismayed by the circle’s resignation. But, he added, “it’s better for me to be walking into a scenario where we begin addressing the problems right away rather than discovering over two years that there’s dysfunction.”

Fraser-Monroe hasn’t let these governance issues affect his vision. This spring, he’ll premiere a new Indigenous ballet for Ballet Kelowna, a smaller company in the Okanagan Valley in British Columbia. In the short term, he’s focused on bringing “T’el” to its home, where his community will see how he’s adapted the story they grew up with. It will also be the first time that Elsie Paul, the 94-year-old elder, sees the ballet and hears her own voice as its narrator, speaking a language that was banned when she was a student at residential school.

“That we’re able to put this onstage is an act of resistance,” Fraser-Monroe said. “It’s a reminder of our incredible resilience.”

The post The Royal Winnipeg Ballet, on the (Bumpy) Road to Reconciliation appeared first on New York Times.