VIGIL, by George Saunders

“Once you start illustrating virtue, you had better stop writing fiction,” Robert Penn Warren wrote. It was once difficult to imagine this dictum might apply to George Saunders.

From the start, in the mid-1990s, he’s been an American original, a briskly whiskered national asset. He’s an ineluctably strange, dark and funny writer whose work has some of Mark Twain’s subversive wit, Kurt Vonnegut’s cosmic playfulness and Donald Barthelme’s laboratory blitzing of high and low culture.

He’s best known for his Booker Prize-winning novel “Lincoln in the Bardo” (2017), which is narrated by quarreling ghosts. But he’s been at his finest in his short stories, which are often about victims and underdogs and bureaucratic absurdities.

In collections like “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” (1996) and “Tenth of December” (2013), Saunders’s wit-to-power ratio remained stubbornly high. He’s been a canny observer of the American experiment, lobbing us his insights from remote corners. His sentences have popped like the car lighters on ’70s-era sedans.

Back in an earlier internet era, the food website Chowhound had a department called “Downhill Alert!” that warned readers when favorite restaurants were slipping. On certain gray days I’ve imagined opening a vest-pocket version of such a department myself. I’ve wanted to file some of Saunders’s recent work inside it.

Over the past 15 years or so he’s slowly drifted, in his writing and other commentary, toward becoming a kind of guru or secular saint, dispensing Buddhism-flecked feel-good messages about practicing kindness and bearing witness. He’s yoked fiction to his project, describing it as something akin to therapy. In a viral commencement speech he declared that reading can help human beings “become more loving, more open, less selfish, more present, less delusional.”

In his nonfiction book “A Swim in a Pond in the Rain” (2021), about reading the Russian masters, he described “people who’ve put reading at the center of their lives because they know from experience that reading makes them more expansive, generous people.”

This is pleasant to imagine, and I suppose it’s true up to a point, but who doesn’t know a lot of big readers who are jackasses from head to toe?

One thing’s certain: The writers who insist on the morally improving nature of fiction, and who robe themselves in the folds of wisdom or beneficence, tend to be the ones to avoid. “If there is any test that can be applied to movies,” Pauline Kael wrote — her test applies to books, too — “it’s that the good ones never make you feel virtuous.”

Saunders’s new novel, “Vigil,” is slim, about the size of Mitch Albom’s memoir “Tuesdays with Morrie” or Richard Bach’s novella “Jonathan Livingston Seagull.” It’s not as soft and shallow and saccharine and strenuously earnest as those books, but it’s not impossibly far off. It’s a hot-water bottle in print form. It’s going to be an enormous best seller for depressing reasons.

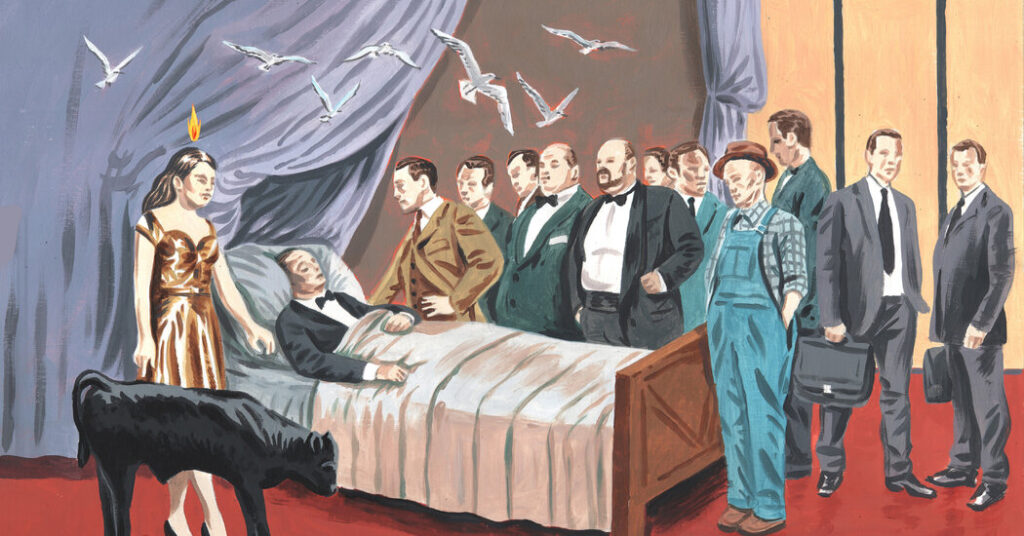

Like “Lincoln in the Bardo,” this novel slides around in the afterlife. It’s about angels of both the amiable and the exterminating variety who crash down to earth to ease the passage, like birthing coaches of a reverse sort, of certain humans.

More specifically, it’s about an angel named Jill who presides at the deathbed of an oil tycoon and determined planet despoiler named K.J. Boone. He’s 87 and dying of cancer. It’s as if Clarence, the angel from “It’s a Wonderful Life,” came down to oblige Mr. Potter instead of George.

Boone is a scoundrel, a true villain, a man who in a series of nesting dolls would emerge after Kenneth Lay and Bernard Madoff. As Jill hovers near his bedside, a second and more avenging angel urges Jill to put the screws to him, to “lead him, as quickly as possible, to contrition, shame and self-loathing.”

Jill demurs. She wonders if Boone couldn’t help being anyone but himself. (This book plays determinately with notions of free will.) Her mission, as she puts it more than once, also seems to be the author’s:

To comfort. To comfort whomever I could, in whatever way I might. For this was the work that our great God in Heaven had given me.

Saunders gets comic mileage out of his arguing, slapstick angels. It’s always been an easy laugh to make a holy person curse or take a pratfall. These angels shriek when they need attention, which is more often than you might imagine. Sometimes, embarrassingly, they drop other, smaller, angels out of their backsides as if they were clumps of dung.

At one point Jill begins to sink into the earth (she’s depressed and upset) and “soon only the tip of my hairdo was visible, scootering along that asphalt surface, somewhat resembling the fin of a shark.” Saunders’s sense of humor is intact, but it feels less organic and more strangled than in previous books.

Before she became an angel, Jill led a circumscribed life. She lived in Stanley, Ind., drove a lime-green Chevelle and worked as a phone operator. She was blown to bits (!!) at age 22 by a car bomb meant for her husband, a cop. Now someone’s left a Slurpee cup near her grave. In the afterlife, she feels fuller, wiser, more expansive.

Jill pays attention to Boone’s story. He feels misunderstood by all the “libdopes” who’ve tried to pull him down. The world may be on fire, but as Elmore Leonard had a character ask in “Swag” (1976), “What do you want, a job or clear sky?”

Boone takes aim at elite, sanctimonious environmental activists:

How did you, Fran, physically get to the Minnesota lake house, when you still had it, dimwit? How did you make your way out of Minnesota and across Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts that one autumn to see the Magritte show in Boston you ended up being so crazy about? How did you get to that bat mitzvah in Palm Springs that was so “transcendent” it made you “rethink your ideas regarding the value of ceremony” or that wedding in Maui that had the fire jugglers, one of whom, supposedly, you made out with? You drove, you flew, you kombucha-making hypocrite.

Saunders’s angels can sink themselves into human beings and deliver unto them, as novelists do, the full force of a different human being. A problem with “Vigil” is that one doesn’t feel the full force of these characters.

The climate talk is ardent but familiar. The biblical countersubversive injunction to love one’s neighbor as oneself turns out to not be enough to hang a novel on. Saunders is making his points too heavily, working to insert wisdom into our open beaks.

The language (“I especially cherished my task,” “Let these ideas enter your heart,” “be moved toward elevation”) can be banal. Saunders’s newfound enlightenment may have done wonders for himself personally, but it’s done his fiction no good whatsoever.

This author has a lot of good will in the bank. He deserves it. Come back from the brink, Mr. Saunders. Please don’t disappear up your own kazoo.

VIGIL | By George Saunders | Random House | 174 pp. | $28

Dwight Garner has been a book critic for The Times since 2008, and before that was an editor at the Book Review for a decade.

The post George Saunders Serves a Heavy Helping of Virtue in a New Novel appeared first on New York Times.