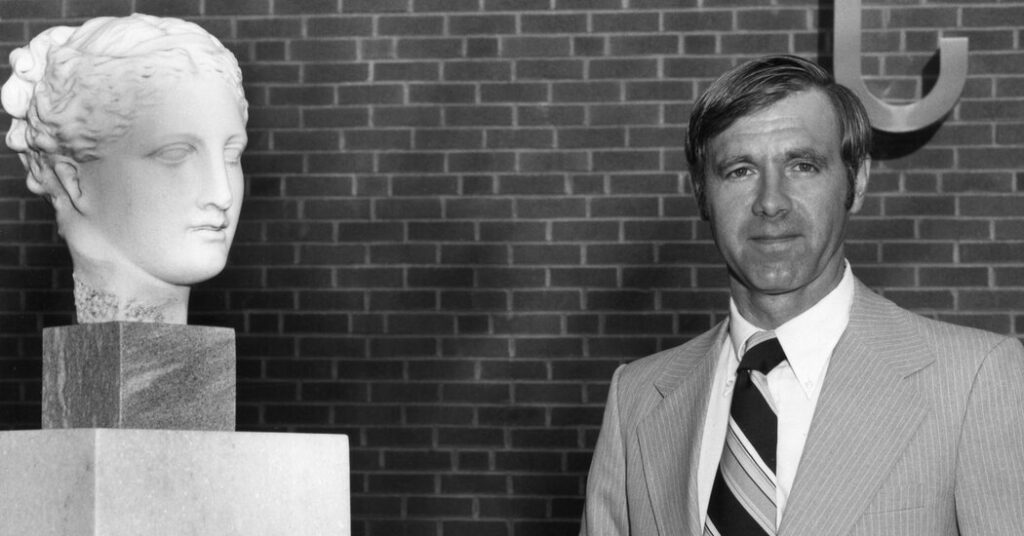

William H. Foege, who developed the vaccination strategy that helped wipe out smallpox in the 1970s, one of the world’s greatest public health triumphs, and who led the United States’ early response to the AIDS epidemic as director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, died on Saturday night at his home in Atlanta. He was 89.

Dr. Mark Rosenberg, a friend and colleague, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

Among public health professionals, Dr. Foege was almost without peer — the grand old man of public health, a field that many feel is under siege by the Trump administration. His successors at the C.D.C., the nation’s primary public health agency, often sought his counsel. In 2012, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest honor given to a civilian.

As director of the C.D.C. under two presidents — Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, and Ronald Reagan, a Republican — Dr. Foege put forth an expansive vision for the agency. He had it focus on leading killers beyond infectious disease, including auto injuries and gun violence, the latter bringing the C.D.C. into conflict with the National Rifle Association and Republicans on Capitol Hill.

After leaving the agency in 1983, he created programs that sharply increased childhood vaccinations on a global scale. Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, a former New York City health commissioner who later ran the C.D.C. under Mr. Obama, invoked a baseball superlative when preparing Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg for a meeting with Dr. Foege.

“I said, ‘Basically, he’s the Babe Ruth of public health,’” Dr. Frieden recalled.

Tall as an N.B.A. forward (he was 6-foot-7) and graced with a patient manner as the son of an Iowa minister, Dr. Foege was serving as a Lutheran Church missionary doctor in Africa when, in 1966, the World Health Organization launched an international program to eradicate smallpox.

The W.H.O. program in West and Central Africa was initially administered by the C.D.C., and it was recruiting as many doctors as it could find to help set up an eradication project in eastern Nigeria. Dr. Foege, who at 29 had earned a master’s degree in public health only the year before, was invited to join.

Along with his wife and a young son, Dr. Foege (pronounced FAY-gee, with a hard “g”) moved to Enugu, the region’s capital. They lived in a four-room mud-walled hut with “no electricity, no running water, no indoor bathroom,” Dr. Foege recalled in an interview in 2023. The nearest telephone was 90 miles away.

There, working as a consultant with Dr. Donald A. Henderson, the W.H.O. smallpox program leader, and Dr. J. Donald Millar, director of the C.D.C. eradication project in West Africa, Dr. Foege trained and deployed teams of specialists determined to vaccinate as many people as possible. At the time, West Africa was considered the most intractable smallpox region in the world.

Highly contagious, often disfiguring and deadly, smallpox had killed as many as 500 million people throughout history. An infected person would be covered with sores of oozing pus and blood that smelled like decomposing flesh. Dr. Foege said he could smell smallpox the minute he entered a room. It was “the scent of death,” he said in a recent podcast.

The conventional modern approach to controlling the disease was vaccination of everybody in an infected region. It was effective as long as there was an adequate supply of vaccine.

In December 1966, Dr. Foege was summoned to control a smallpox outbreak 90 miles east of Enugu. But unable to acquire enough vaccine to inoculate everyone in the area, he proposed a more efficient, surgical approach.

His team identified those infected in the villages, isolated them, and vaccinated everyone who had been in contact with them. They then vaccinated everyone who had been in contact with that second group. As a next step, they vaccinated people who had gathered in primary public places, like markets.

In effect, Dr. Foege and his team built a ring of containment around the initial outbreak, halting the spread of the disease. He said the strategy — now known as “ring vaccination” — was based on principles he learned when he spent summers fighting wildfires in the American West as a younger man. Fire crews worked to extinguish the heart of the fire while trying to prevent its spread by building fire lines, perimeters cleared of vegetation, often down to bare soil.

“It wasn’t a new strategy,” Dr. Foege said in an interview for this obituary in 2020. “What was important was that we got rid of the first strategy, which was mass vaccination. We showed that you could forget about mass vaccination and go right to the second part.”

A Daring Raid

When civil war broke out in Nigeria, pitting secessionists in the east against the federal government in Lagos, Dr. Foege’s family was evacuated. But Dr. Foege, having rejoined the C.D.C., stayed behind in the eastern region to lead the effort to stamp out smallpox there. It was dangerous work: He was constantly encountering roadblocks, often maintained by armed teenage rebels, who, he later wrote, “mixed guns, alcohol and bravado.”

When officials in Lagos cut off vaccine supplies to the east, threatening the success of his program, Dr. Foege was defiant, and undeterred. He and one of his C.D.C. team members hopped in his white Dodge pickup truck and drove 350 miles, across a bridge over the Niger River and into the capital city to raid a government warehouse.

While his C.D.C. colleague distracted a security guard, Dr. Foege loaded up the truck with stolen vaccine, cold packs, jet injector parts and other supplies. He drove back, terrified of being caught — only to run into a wall of trucks and bulldozers blocking the bridge at the river’s western edge, cutting off his passage back to safety. He fast-talked his way through in a meeting with the rebel leader.

“I explained that we had just stolen vaccine from the federal government, and he was happy about that,” Dr. Foege recalled in an interview with The New York Times in 2023. “He cleared a path for us, and when we got across the bridge, we could breathe a sigh of relief.”

By the summer of 1967, smallpox had been eradicated in eastern Nigeria, and Dr. Foege reported the results at a C.D.C. meeting in Ghana. Dr. Millar and his C.D.C. specialists in Africa soon embraced the containment approach as the primary tactic for eradicating smallpox in West and Central Africa, a goal that was achieved in the spring of 1970.

Dr. Foege, as a C.D.C. consultant, was next dispatched, in 1973, to help design and lead smallpox eradication projects in India, one of the last countries where the disease still had a hold. He had served as a Peace Corps volunteer in India in the early 1960s and was familiar with the country. Again, his family, which had grown by two more sons, accompanied him.

The challenge in India was consistent with what he had learned in Africa. Working with the Indian national and state authorities, he shuttled between planning meetings and the field as a senior leader in an eradication program that grew to enlist tens of thousands of investigators and technicians.

The number of villages where the disease was present, along with the number of new smallpox infections, began to fall in 1974, when political interference almost derailed the project. The minister of health in the northeast state of Bihar had become alarmed at what he viewed as a slow pace in controlling infections and vowed to replace the surveillance-containment program with mass vaccination.

Doing so would have wasted months of logistics preparation, training and early successes in reducing infections. “Did he have any idea that he was threatening to put the entire India program, indeed the entire global program, in jeopardy?” Dr. Foege wrote in “House on Fire: The Fight to Eradicate Smallpox (2011), one of several books he wrote.

At a meeting with the minister to decide the issue in May 1974, a young Indian doctor, a field technician for the project, stood up and described himself as just a poor village man. In the event of a fire, he said, no one in his village poured water on houses that weren’t burning. Instead, as in the surveillance-containment strategy, they poured water only on the burning house.

“A chill went up my spine,” Dr. Foege wrote. “This man condensed all the work, discussions, discoveries and massive human effort of the previous seven months into a few words and the indelible image of a fire.”

The Bihar minister backed off. A year later, the last case of smallpox in India was eradicated.

A Scourge Defeated

The world’s last known smallpox case was that of a cook in Somalia in 1978, Dr. Foege said. Two years later, the W.H.O. formally declared that smallpox was the first infectious disease to be altogether eliminated. Dr. Foege, Dr. Henderson and Dr. Millar are widely credited with being the principal architects of that eradication.

Of the three, Dr. Foege was the last survivor. Dr. Millar died in 2015, Dr. Henderson in 2016.

Dr. Foege was appointed to direct the C.D.C. in 1977, during the Carter administration. Four years later, the C.D.C. published the first reports of a “rare cancer” in homosexual men — the first hint of the coming AIDS epidemic. Dr. Foege, grappling with budget cuts and an indifferent Reagan White House, “borrowed money and borrowed people” from other programs, he said, to build a task force of epidemiologists to investigate.

Over the next two years, until he left the C.D.C., Dr. Foege navigated the political currents in Washington around a highly charged epidemic, as scientists raced to identify the virus causing the so-called “gay cancer.”

He privately pushed his higher-ups at the Department of Health and Human Services to ask Congress for more funding. When they refused, he told lawmakers that the C.D.C. had what it needed. When Democrats in Congress wanted him to provide the names of men infected, Dr. Foege refused, saying patients deserved their privacy. He stepped down in 1983, he said in an interview, partly out of frustration with the Reagan White House.

After leaving government, Dr. Foege focused on strengthening global health programs for children. In 1984, a working group composed of members of the W.H.O., UNICEF, the World Bank, the United Nations Development Program and the Rockefeller Foundation recruited him to lead what was christened the Task Force for Child Survival, based in Atlanta, its mission to increase global immunization of children.

When the task force started, roughly 15 percent of the world’s children had received at least one vaccine. By 1990, the rate had increased to 80 percent.

Dr. Foege often said that all public health is global health, by which he meant that infectious disease knows no borders. He spoke frequently of the moral obligation to be a “good ancestor,” said Dr. Rosenberg, who worked with Dr. Foege at the C.D.C. and is president emeritus of the task force, since renamed the Task Force for Global Health.

“He thought that public health has a basic responsibility to take care of not just the people right next to us, but everybody,” Dr. Rosenberg added, “and he expanded that concept of everybody in the world to everybody who’s going to be born in the future. That was a tremendous leap, a visionary statement.”

In 1986, Mr. Carter and his wife, the former first lady Rosalynn Carter, named Dr. Foege executive director of the Carter Center, a nongovernmental organization in Atlanta focused on global conflict and health.

“Bill Foege was a pre-eminent public health practitioner who dedicated his life to what he called science in the service of humanity,” Mr. Carter said in a statement for this obituary, issued before his own death in December 2024. “He saved the lives of millions of people around the world.”

Home Was a Parsonage

William Herbert Foege was born on March 12, 1936, in Decorah, Iowa. He was the eldest of two boys and the third eldest of six children raised in a series of parsonages by his parents, the Rev. William A. and Anne Erika Foege.

He received a B.A. in biology from Pacific Lutheran University, in Parkland, Wash., in 1957, and a medical degree from the University of Washington in 1961. He spent a short time with the Peace Corps in India and received a master’s degree in public health from Harvard University in 1965.

In 1997, Dr. Foege joined the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta as a professor of international health. Two years later, as Bill and Melinda Gates were preparing to launch their world health foundation, Mr. Gates recruited Dr. Foege to develop programs to fight disease. As a senior fellow with the foundation for 10 years, he influenced its decision to invest $750 million to start a public-private global child-vaccination project called Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Dr. Foege was described by friends and colleagues as someone who was comfortable with taking risks in pursuit of a goal, a trait that perhaps helped explain one of the few missteps of his career: his defense of the failed blood-testing technology promoted by Theranos, the Silicon Valley start-up founded by Elizabeth Holmes.

In 2016, two years after he joined the company’s board and as the effectiveness of the Theranos technology was coming under intense scrutiny, Dr. Foege published an opinion article on the political news site The Hill. “In my opinion, the very foundation of Theranos’ inventions — and its hundreds of patents — is credible,” he wrote.

In March 2018, six months before Theranos collapsed, the Securities and Exchange Commission charged Ms. Holmes with fraud for misleading investors about the capabilities of the technology and overstating the company’s revenues. In 2022, she was found guilty on four of 11 counts of fraud and sentenced to a little more than 11 years in prison.

Dr. Foege’s honors included the 1996 Calderone Prize, the most prestigious public health award; and the 2005 Public Welfare Medal, the National Academy of Science’s highest award.

Survivors include his wife, Paula (Ristad) Foege; two sons, Robert and Michael; three sisters, Mildred Toepel, Annette Stixrud and Carolyn Hellberg; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. His eldest son, David, died in 2007.

In his later years, Dr. Foege became a prominent critic of both the first and second Trump administrations’ actions regarding public health. In 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic was sweeping the world, he criticized the White House for initially downplaying the threat and making inaccurate public statements about it.

“We’ve broken every rule that we’ve learned on disease control,” he said in the interview for this obituary that year. “The first and most important rule is to know the truth. You have to set up a surveillance system to know the truth, otherwise you’re responding blindly. The truth changes every day in the White House.”

He was furious with the current health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has taken steps to dismantle many of the programs that Dr. Foege helped build, and whose views on vaccination he regarded as dangerous.

“Kennedy’s words can be as lethal as the smallpox virus,” he wrote in an opinion piece for the health and science website STAT in August, after Mr. Kennedy had promoted cod liver oil as a treatment for measles and called vaccination a personal choice. In an email message at the time, he wrote, “I had no idea I would be this angry at the age of 89.”

If there is a single accomplishment for which Dr. Foege will be remembered, it is the eradication of smallpox, which killed 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Among the books on his living room coffee table was one published in 2009 and titled “Scientists Greater Than Einstein: The Biggest Lifesavers of the Twentieth Century.”

The book tells the stories of 10 scientists who were not famous, but whose work had an outsize impact on humanity. The cover drawing is a silhouette of those featured inside. There are no names, but Dr. Foege’s presence is obvious. He stands a head taller than the rest.

Sheryl Gay Stolberg covers health policy for The Times from Washington. A former congressional and White House correspondent, she focuses on the intersection of health policy and politics.

The post William H. Foege, Key Figure in the Eradication of Smallpox, Dies at 89 appeared first on New York Times.