He props his smartphone against a pile of books and adjusts the settings so the screen won’t go dark. He sets a timer. Then he waits.

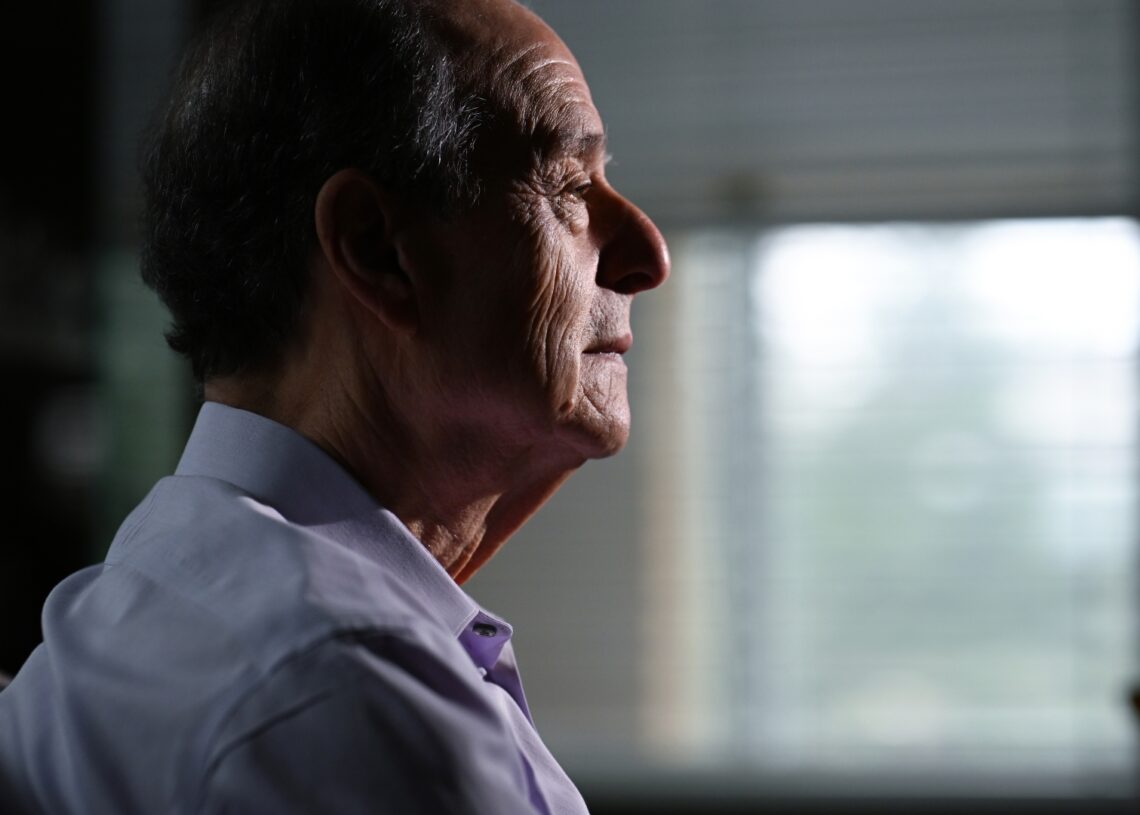

Eyes closed, Samuel A. Simon traces his breath from his ankles up through his chest, checking in with each part of his 80-year-old body before he begins. A purple binder holding a play script rests in his hands; the opening lines come from memory.

Midway through, he falters.

“I’m getting all over the place,” he mutters, flipping a page. He finds his spot, then continues.

Simon was diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in 2022. As his memory has grown less reliable, he has turned his experience with the disease into a one-man play, “Dementia Man, An Existential Journey,” performing it publicly as a way to hold on to a sense of self.

But the work doesn’t stop when rehearsal ends.

Outside of the play, much of Simon’s day is organized around staying present at medical appointments, keeping up with a calendar that includes volunteering at his synagogue and advocacy work in Northern Virginia, and the small conversations he and his wife, Susan, return to again and again as they try to stay ahead of what’s changing.

After faltering during his latest run-through, Simon tries to recall the name of a doctor he mentions in his script. He pictures circling the name in his mind, then tries again.

“It’s the first doctor I see,” he tells Susan. Another pause. “God, what do I call him — doctor who?” After several more beats, the name arrives: Dr. Howard.

Simon sometimes gestures toward his wife for help during rehearsals, and she quietly feeds him the next line.

During the actual performances, while sitting in the front row, she knows not to rush him through these moments.

“That’s the lesson I’ve learned in all this,” she says. “Even when he’s trying to give you a word that he can’t think of, I used to jump in and say, ‘Describe it for me.’ But if I wait and give him the chance, it will come.”

The exchange reflects an undercurrent in the play that pulls audience members without Alzheimer’s into what the disease can feel like from the inside.

“Vanishing is my worst fear,” Simon will say onstage.

The Nothingness Place

Remembering one’s lines before a live audience is daunting — even without a disease that steadily erodes memory.

Simon has chosen to take on that challenge anyway. For nearly three years, he has performed “Dementia Man” in small theaters and public libraries across the country. He has also turned the work into a book, using it as a way to hold on to a sense of who he is and the life he remembers living.

That life includes his years as a young lawyer working alongside renowned consumer advocate Ralph Nader on property tax reform. It also includes a nearly 60-year-long marriage that sprang from a chance encounter in El Paso when they were dating other people, and the two children they later raised — one of whom would become a prominent state delegate in Virginia’s General Assembly.

Simon has long described himself as a troublemaker — someone wired to push at systems that are dysfunctional and don’t sit right with him.

In 2016, the system that stopped functioning properly was his own.

That year, Simon found himself driving on the wrong side of the road about 10 miles from his home in McLean, Virginia, alerted by a chorus of honking horns. When he mentioned the incident to friends later, some of them downplayed it, saying they had once done the same thing.

Several months later, it happened again — this time on the familiar drive home from the local diner where he and a good friend ate lunch every Friday. Simon told no one.

What finally overwhelmed him were episodes he struggled to describe at the time: moments when his body and mind seemed to separate, when he felt himself slip into what he would later call the “Nothingness Place” — a sensation he has likened to floating, briefly, outside himself. The experience left him frightened and disoriented.

Eventually, Simon spoke up. He went first to his internist, describing the driving incidents and the disorientation that followed. He recalled the internist initially chalking it up to Simon being an “overeducated” man who was reading too much into the ordinary effects of aging.

But when Simon tried to describe the Nothingness Place, the internist’s response shifted. Simon was referred to a neurologist, the first of several specialists he would see as he tried to make sense of what was happening.

In 2018, Simon was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, a condition that can precede dementia but does not always progress the same way. The label helped explain some things, including the slips and disorientation, but it offered little clarity about what came next.

This uncertainty lingered until 2022, when Simon was told his cognitive impairment was caused by early-stage Alzheimer’s. The diagnosis of a disease that can cause life-threatening complications brought a measure of clarity, he said — and, with it, a new kind of fear.

Encouraged by friends, Simon began to consider bringing the experience to the stage.

‘The Actual Dance’

Years earlier, Simon had written and performed another one-man play — “The Actual Dance” — rooted in one of the most frightening periods of his marriage.

In the early 2000s, Susan was diagnosed with Stage 3 breast cancer. Doctors told Simon she would not survive. Simon recalled lying awake beside her at night, listening for her breath, afraid of what might happen if he looked away. The idea of losing Susan, he said, felt like losing half of who he was.

Around that time, Simon was taking improvisational theater classes — initially as a form of professional development after decades spent as a lawyer, advocate and businessman. Through that work, he realized he needed a way to release what he had lived through.

The script took shape in 2012. Its title came from a vision that had stayed with him after Susan’s diagnosis: the two of them dancing in a ballroom, surrounded by everyone they had ever loved, before she dies in his arms.

“I’m about to lose the person I love most in my life,” Simon recalls thinking. “And I have to imagine holding her as she takes her last breath.”

But after more than a decade of performances, even after her cancer went into remission, Simon began to forget the lines as his cognitive impairment deepened during the pandemic.

New symptoms followed. He became more agitated and began worrying about hurting Susan and others he loves as his control slipped.

The balance in their marriage was shifting.

The strain surfaced during a meeting Susan requested with a social worker.

There, Susan shared something she had struggled to say aloud: that Simon sometimes scares her. She worried, she said, that he might hurt her — even if he didn’t mean to.

The journey

“Switzerland,” Simon says onstage, pausing long enough for the word to hang.

In “Dementia Man,” it’s shorthand for assisted suicide — a nod to the fact that people with terminal or degenerative illnesses can legally end their lives with medical help in that country.

Simon introduces Switzerland early in the performance, before the audience fully understands where the story is going.

For his son Marcus Simon, the Virginia state delegate, hearing that word in the audience landed heavily. He says it was disorienting to see moments he had lived through appear onstage, compressed and sharpened — and to learn, in real time, about fears his father had never voiced to him directly.

“Parents sometimes want to protect us kids, not burden us with every diagnosis or thought that’s going through their heads,” Marcus Simon says. “It puts you in the mindset of what comes next, and how I’m going to take care of him — not just physically, but make sure his wishes and wants are respected.”

The elder Simon is aware that his perspective is unique. The play, he says, is his way of pushing back on the idea that people with dementia just disappear quietly or lack the ability to make meaningful contributions. Simon also volunteers as a subject for brain research whenever he qualifies — another way, he says, of trying to make the time he has matter.

His doctors have told him the work appears to be helping him navigate the disease as it advances.

“If I’m going to die from this, why waste the trip?” he says about the journey he’s been on with Alzheimer’s. “Our life has been as good as it can be. I just want to do the best I can until I can’t — and be a net positive for the world.”

After performances, Simon says, he is often approached by people who’ve lost a parent or spouse to dementia — thanking him for offering a lens into what their loved ones might have been going through.

Susan remembers feeling overwhelmed at first, watching her husband perform “Dementia Man.” There were nights she sat in the audience with tears in her eyes, watching intimate moments from their shared life take shape onstage.

Now, she says, the feeling is different.

“Thank God he has a purpose.”

What to keep

As Simon’s symptoms progress, time has taken on a sharper edge. He schedules performances of “Dementia Man” no more than a few months in advance, wary of committing to dates his health might not allow. Other decisions once left for later have become unavoidable — including what to do with the life he and Susan have built inside their home.

Every two weeks, the couple meet with a downsizing specialist to work through decades of accumulated material: a trove of books, files and personal archives that trace Simon’s past. Deciding what to keep and let go of is excruciating.

There are mementos from his years as a public-interest lawyer — including a framed 1971 New York Times story about his consumer-protection work with the headline “Nader-Raiding No Plush Job” and a poster featuring the title of Nader’s landmark book “Unsafe at Any Speed,” which helped force seat belts and product safety into federal regulations.

The poster bears a handwritten note from Nader: “To Sam, who will never forsake the public interest work.”

There are also artifacts tied to his faith and family history, including a small banking book that once belonged to his father and Jewish communal materials from his years of leadership at his Falls Church synagogue.

The couple plan to move next year into a memory care community, a shift that will require letting go of much of what fills the space.

“I have all the stuff from the original Nader world. What do I do with that?” Simon asks aloud to no one in particular. “I don’t want to have an ego and say, ‘I’m important’ — but I just don’t know what to do.”

Other items raise different questions. A poster signed by Salvador Dalí. A 17th-century seder plate. The downsizing specialist has flagged both for review by an auction company.

They haven’t yet reached the boxes in the attic.

Someone suggested to Susan that they photograph or digitize certain items. Simon resists the idea. He has said that keeping virtual versions of things that once mattered feels wrong — another kind of disappearance.

“I don’t want to say I’m worried, but I’m more aware and anxious now about getting everything done,” Simon says. “My biggest challenge some days is trying to figure out: What’s the right way to preserve your legacy?”

To keep pace, the downsizing specialist now primarily meets with Susan. The goal is a practical one: to move forward without letting the process harden into regret.

On a recent afternoon, the couple worked through the stacks, pausing as decisions slowed.

Simon picked up a thick, weathered book.

“What the hell is this?” he says.

He turned it over in his hands.

“Oh — an atlas.”

The post In a one-act play, a man chronicles his own dementia appeared first on Washington Post.