The sixth in an occasional series of profiles on Southern California athletes who have flourished in their post-playing careers.

It’s been nearly four decades since Vince Ferragamo took his last NFL snap and most of his football exploits have been eclipsed by the passage of time.

The 509 passing yards he had in a 1982 loss to the Chicago Bears, most in an NFL game in 31 years? It’s been bettered 14 times. The club-record 30 passing touchdowns in 1980? That’s now seventh on the team’s single-season list.

But there’s one milestone no man, not even Father Time, can ever take away from Ferragamo. At the end of the 1979 season, he became the first quarterback to take the Rams to the Super Bowl.

The team has returned to the NFL championship game four times since then. A Rams’ win over the Seattle Seahawks in Sunday’s conference title game will keep alive Matthew Stafford’s chance to become the first quarterback in franchise history to win the Super Bowl twice.

Ferragamo, however, got them there first.

“There was just something so mystical about the whole thing,” says Ferragamo, who made his first NFL start that season.

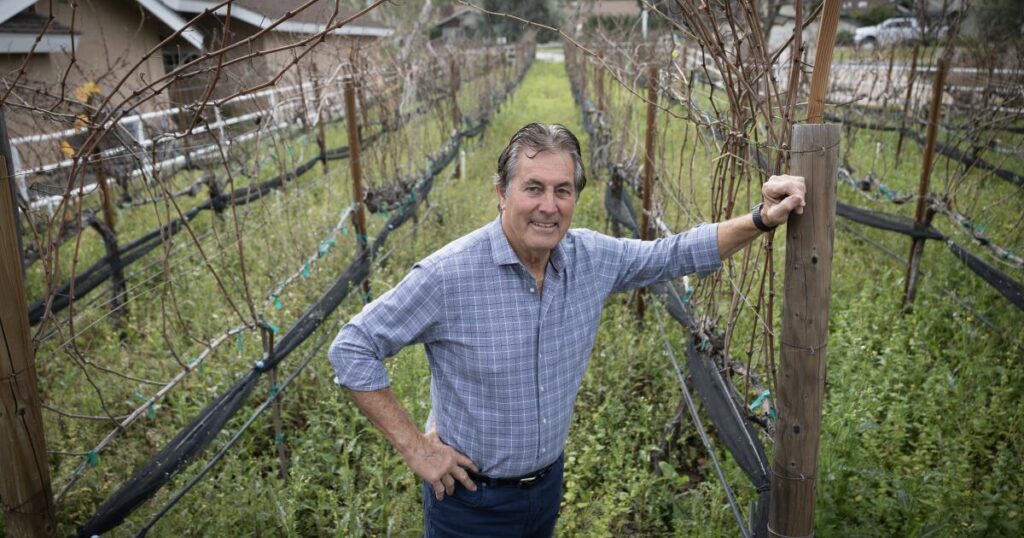

He competes in a different arena now, managing a mortgage company and an eponymous real estate firm. He and his wife, Jodi, have helped raise millions for a variety of local charities and they also grow the grapes for their boutique wine label on 230 vines next to their home in central Orange County. The transition from the gridiron to the regular grind has been seamless.

“Football prepares you for life beyond football,” he said. “More than anything it adds credibility to my work. They have to trust you. We’ve built our whole company around that.”

Ferragamo’s football career also depended on earning trust. Although he was tall and blessed with a strong right arm, Ferragamo had to win over critics everywhere he played, beginning in high school where he had to convince his brother, the coach, he should start.

After two years at Cal, where he had to share playing time, Ferragamo transferred to Nebraska and became an All-American. Yet the Rams waited five picks and four rounds before selecting him in the 1977 draft, then handed him a clipboard and told him to find a spot on the bench.

“There was a lot of trials and tribulations. A lot of ups and downs,” Ferragamo said. “But I think it teaches how to live life that way. Because every day you wake up with struggle.”

Yet for one glorious two-month stretch in the winter of 1979-80, the struggle was over and Ferragamo was arguably the best quarterback in the NFL, engineering one of the most improbable playoff runs in Rams history.

After starter Pat Haden was injured and rookie backup Jeff Rutledge proved ineffective, Ferragamo took over a team with a losing record. He was supposed to just finish out the season; instead, he carried the Rams to four consecutive victories.

He led the Rams to road playoff wins over Dallas and Tampa Bay, the first time in franchise history the Rams had won two playoff games in the same season.

“He began to show us that he had the arm to make the plays,” said Hall of Fame offensive tackle Jackie Slater, Ferragamo’s longtime teammate. “That’s when everybody began to rally to give the young guy as much support as we possibly could.

“Everybody kicked it up a notch. And that’s what makes a good quarterback right? His leadership brings that out of you, makes you all a little bit better than you might have been without him.”

In the Super Bowl, played before nearly 104,000 people at the Rose Bowl — still the largest crowd to attend a Super Bowl — Ferragamo had the Rams leading heading into the fourth quarter before the Pittsburgh Steelers rallied to claim their fourth championship.

He won just one more playoff game, retiring seven years later following a career that took him to four cities and two countries — but just one Super Bowl.

“I don’t really have any regrets when I look back on my career,” Ferragamo, 71, said earlier this month, surrounded by football memorabilia in his second-floor corner office in Anaheim Hills. “If everything was just carte blanche and just easy for you, it wouldn’t be worth living. So there’s always a challenge.

“The ups and downs, maybe that’s what kept me going.”

Ferragamo, the youngest of four children, grew up in Wilmington, which was a gritty, working-class city in the 1960s, much as it is today. His father, Vince Sr., a World War II veteran who dropped out of the school in the eighth grade, was street smart and tough, working his way up to union president of UAW local 923 at Ford’s sprawling Pico Rivera plant.

“He was a great role model for me,” Ferragamo remembered. “We were the only Italian family in the neighborhood. It was, you know, tough, tough beginnings. It makes you desire and appreciate things and help others.”

“That’s what football is,” he added. “If I can help my receiver look good, we all look good.”

And Ferragamo certainly looked good when he threw a football.

“When he was about 14 years old, he’d go out in the front of the house and he’d throw the ball from one light pole to another. It’s a long way,” said Chris Ferragamo, Vince’s eldest brother and his coach and Banning High.

“He loved doing that kind of stuff. That’s how he started his throwing ability.”

Still, Chris, who would go on to win eight City Section titles at Banning, already had a quarterback when Vince joined the team as a sophomore, so he wasn’t about to hand him the starting job just because they were brothers.

“People thought it was a cake walk. And it wasn’t,” Vince said.

“He never wanted to play me. The other coaches said, ‘Hey, you’re crazy. You’ve got to play him. He’s better than the other guys.’”

So Chris Ferragamo said he talked his returning quarterback into moving to wide receiver and Vince went on to become a high school all-American and the City Section player of the year, eventually earning induction into the California High School Football Hall of Fame.

That earned him a scholarship to Cal, where he played 22 games in two seasons, throwing nearly twice as many interceptions as touchdown passes. The Bears were placed on NCAA probation shortly after Ferragamo enrolled and when he found himself sharing time with Steve Bartkowski at quarterback, Ferragamo transferred to Nebraska and proved himself again, leading the Cornhuskers to a 10-2 record in 1975 and the No. 1 spot in the AP preseason poll a year later.

The critics weren’t convinced, so Ferragamo fell to the fourth round of the NFL draft where he was the 91st player — and fourth quarterback — selected.

“Basically he had to prove himself every place he went,” Chris Ferragamo said. “He always did.”

Playing behind Haden and an aging Joe Namath, Ferragamo threw just 15 times as a rookie for a team that lost in the first round of the playoffs. A year later, as Haden’s backup, he threw just a few more passes, the last in a one-sided loss to the Cowboys in the NFC championship game.

Ferragamo finally got his chance late in 1979. With the Rams struggling at 5-6 and Haden out because of an injured finger on his throwing hand, coach Ray Malavasi turned to Ferragamo, who lost just one of seven starts to get the Rams to their first Super Bowl.

“We knew Vince had a good, strong arm. And we knew he hadn’t played a lot of NFL games,” Slater said. “So I think that everybody just kind of relaxed and said that we’ve got to help this young guy be successful. Let’s just make sure we do our jobs and then hopefully our quarterback position won’t be a liability.

“And that’s kind of the way it worked out.”

The play that sealed Ferragamo’s status as the team’s new leader came with just over two minutes remaining in a first-round playoff game in Dallas. With the Rams trailing 19-14, Ferragamo threaded a pass to Billy Waddy, who was surrounded by six Cowboys. Waddy escaped the pack to score on the 50-yard play, Ferragamo’s third touchdown of the game and one he described as “a spiritual pass, one that was guided from up above.”

The almighty apparently abandoned the Rams three weeks later when they twice blew leads in a 31-19 loss to Pittsburgh in the Super Bowl. Ferragamo had played well, throwing for 212 yards, although a late interception set up the Steelers’ final touchdown.

Still, the Rams had established themselves as one of the top teams in the NFL. They had made seven consecutive playoff appearances and just two of their starters were over 30. With the 26-year-old Ferragamo taking over at quarterback, the team looked primed to become a perennial Super Bowl contender.

“We felt like it was going to be a good team for a long time,” Slater said.

Instead, the Rams won just five playoff games over the next 19 years and didn’t return to the Super Bowl until the 1999 season, their fifth year in St. Louis.

“They dismantled the team after our Super Bowl run, which was unfortunate for the L.A. fans,” Ferragamo said. “They had something in place that could have really been great.”

Ferragamo’s honeymoon was even shorter. After a spectacular post-Super Bowl season in which he set franchise records by throwing for 3,199 yards and 30 touchdowns, Ferragamo sought a raise from the $52,000 he earned in 1980, the lowest pay for a starting quarterback in the NFL. The Rams reportedly countered with a $250,000 offer during the season, then sweetened that by another $75,000 afterward.

But Ferragamo, angry that the team hadn’t given him a new deal after the Super Bowl, turned them down and jumped to the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League, who offered a four-year deal worth about $2 million. That’s when things started to go off the rails.

A classic drop-back passer, Ferragamo wasn’t suited to the Canadian game, which put a premium on quarterback mobility. As a result, he threw just seven touchdown passes and was intercepted a league-high 25 times, eventually losing the starting job as Montreal stumbled to a 3-13 season.

Team owner Nelson Skalbania, an engineer and businessman from Vancouver, had an even worse year, first dissolving his company, then declaring bankruptcy, which forced him to return the team to league after one season. Ferragamo, whose contract was not guaranteed, was suddenly unemployed.

“I went from the Super Bowl back to the bottom,” he said.

He also went back to the Rams, who signed him to a series of one-year contracts valued at approximately $300,000. Over the next three seasons he lost more games than he won and threw more interceptions than touchdown passes before moving on to Buffalo, which had the worst record in the NFL in his only season there.

His final three games came in a mop-up role for a Green Bay team that went 4-12 in 1986. At 32, his football career was over. But his second act was just beginning.

Jodi Scarpello was a freshman journalism major at Nebraska when a high school friend introduced her to a transfer student from California. The introduction wasn’t necessary since football was a religion in Lincoln and everyone knew about the handsome quarterback who had come over from Berkeley.

“I knew what he was doing there,” Scarpello said. “I knew football when I met him.”

Three years later, after Ferragamo had graduated to the NFL, the couple married and a passion for football became something they shared.

“I used to watch game film. We just watched at home on a reel-to-reel projector,” Jodi said. “I used to sit at games and call plays and people would think ‘how do you know that?’ I’m a good student.”

Being the wife of a Super Bowl quarterback had other perks as well.

“I met, at a charity banquet in Washington D.C., and had a conversation with Coretta Scott King,” she said. “We just talked about our children. But in my head I was thinking ‘Oh my God, that is really cool!’

“We got to do a lot of traveling and that kind of stuff. It’s pretty amazing, some of the things we were able to do.”

There were also drawbacks. Unlike today, when wives and children are invited on to the field and sometimes into the locker room, in Ferragamo’s day teams maintained a distance between players and their families.

“When Vince was playing, he left on Friday and I didn’t talk to him until he got back on Sunday night,” Jodi said. “He got hurt one time in Buffalo and he’s rolling around on the ground. He keeps holding his arm. Maybe it’s his hand. I’m thinking, I’m not going to know.”

When it all came to an end after that dismal season in Green Bay, the Ferragamos still had more than half their lives ahead of them — yet they were facing a life without football for the first time. Vince had never done anything but play football. Now he would have to learn to live without it.

So he called an audible and less than a year after retiring, he had a real estate license; eight years later he had his own real estate company. He would later add a mortgage fund.

“When I retired, I said ‘what am I going to do’,” remembered Ferragamo. “A lot of guys, when they get out of football they fall on hard times. But I was able to transfer into another field. I also did some investing while I was playing, which was smart. I had some money that could help get me through the transition.”

The couple, married 47 years, also had three children — all daughters, Cara, Venessa and Jenna, which proved to be a blessing, their mother said, since none would feel pressured to follow their father into football.

“If they were playing now they could probably go play flag football,” Jodi Ferragamo said. “I think it was probably better not to have those kind of comparisons. And they’re all successful in their own way.”

But if selling real estate paid the bills, wine would become Ferragamo’s new passion.

With his football money he had purchased an acre lot in a largely equestrian community in central Orange Park Acres converted a horse corral on the property into a vineyard and became a self-taught winemaker, producing award-winning Italian Super Tuscan-style blends. He also became a certified sommelier and lecturer who teaches a community education course on the art and science of winemaking.

“I’m Italian,” he said. “I love all wines.”

The Ferragamos also created a foundation and have supported multiple causes, ranging from the Special Olympics, Boys & Girls Club and the Alzheimer’s Assn., to the Ronald McDonald House and the Orange Coast Medical Center, where a wing has been named in recognition of the Ferragamo Foundation’s contributions to the fight against breast cancer.

But football isn’t totally in the rear-view mirror. Ferragamo still attends a couple of Rams games each season, runs a flag football league for grade-school kids and co-hosts the weekly sports-talk show “On Point Live” with Slater.

“He hasn’t changed. He’s still Vince,” said Slater, who has known Ferragamo since his rookie season. “He’s a confident guy, smart guy. And he’s very competitive. So he’s the same guy.

“Kind of laid back. Family guy. Just loves the game of football.”

The ex-teammates remain close even though Slater says he almost got Ferragamo killed in the quarterback’s penultimate season with the Rams.

“I got beat clean,” the hulking right tackle said. “My old high school nemesis, Ben Williams from the Buffalo Bills, beat me and Vince was standing there about to throw and he just put his helmet right in the middle of his back. Oh, it was an ugly thing to see.

“Blood comes flying out of his mouth. I don’t how he bloodied his mouth when he got hit in the back.”

That, Ferragamo admits, wasn’t exactly the most memorable moment of his career. Asked to chose the highlight of those 10 years, he leans back in his chair, folds him arms across his chest and thinks for a moment before settling on the obvious answer.

“It’s probably the Super Bowl,” he says, “and leading up to the Super Bowl.”

After all he was the first Rams quarterback to get that far, a distinction he’ll own forever.

The post From Rams star to sommelier: Vince Ferragamo turned football lessons into life achievements appeared first on Los Angeles Times.