Send questions about the office, money, careers and work-life balance to [email protected]. Include your name and location, or a request to remain anonymous. Letters may be edited.

A Very Short Tenure

Dear Work Friend,

I’m four months shy of a year into a role that has become unsustainably broad, with constantly expanding scope and shifting expectations. Despite great feedback from my peers and measurable impact, the management dynamic makes it difficult to succeed: my manager’s feedback is largely corrective rather than enabling, priorities change without corresponding trade-offs and accountability for outcomes sits with me even when inputs are outside my control.

Complicating this further, the leadership structure offers no meaningful escalation or mediation path. My manager is in a relationship with the company owner, and another relative is the head of H.R., which limits the ability to address these issues constructively. My concerns have fallen on deaf ears, and the response was essentially: “That’s just how it works here.”

I’m 40 and don’t take short tenures lightly, but I’m concerned the role is set up in a way that makes long-term success unrealistic. I absolutely love what I do, and my team relies on me for a lot because they know they can. But I have never felt worse about myself because of the borderline harassment I endure.

How can I explain this honestly in interviews when asked why I’m leaving, without sounding negative or defensive?

The specific question you’re asking has a pretty short and straightforward answer, which I promise I’ll answer. But I get the sense that there’s another question you’re actually asking, lurking behind the articulated one, animating the rather long description of conditions at your current job — a question that’s something like, “Am I justified in hating this job and wanting to quit so soon?”

The answer to that question is “yes.” Allow me to reassure you: If even part of the dynamic you’re describing is accurate, you’ve found yourself in an impossible position within a dysfunctional company, and you are absolutely right to seek a quick exit.

And even if you’re somehow misconstruing the situation, and it’s a “you” problem rather than a “them” problem, I’m not sure my advice would change. Sometimes a job is just a bad fit, and you’re not doing yourself or your employers any favors sticking it out. They want someone who does the job to their (perhaps unreasonable) parameters, and you want a job with clearer expectations and less agita — and maybe also one where your manager’s paramour doesn’t sign your paychecks.

You seem particularly concerned about the relatively short length of your tenure. But eight months is more than enough time for an experienced professional to know when a job is not right. And recruiters and H.R. professionals are not going to be fazed by a single short job across a longer and generally stable career journey — especially if you can explain the problem clearly.

Which gets us to your actual question. I worry that your feelings of insecurity (or guilt) about leaving this job are leading you to over explain, as though you were unburdening yourself to a therapist, or perhaps testifying in front of a judge. And while an advice columnist is effectively both of these things — and therefore eager to get the gory details — an interviewer is neither. They are not really interested in detailed specifics of your bad workplace and the last thing they want to hear is an elaborate rehash of a series of disputes.

In fact, what they are looking for is reassurance that this blip won’t be a factor at all in your future career, either as a confidence-killing mistake or as a harbinger of things to come. So be succinct, confident and neutral. Say something like: “I was brought in to do a specific job, at which I made measurable impact. Over time, it became clear the organization needs something different than what I was hired to do. I’m looking for a role where I can focus on my strengths and contribute at the level I do best.”

If they press for more details, you don’t have to say anything more than: “The expectations evolved in ways that made it hard to do my best work long-term. I’d rather make a thoughtful move now than wait until I’m burned out.”

Most importantly, believe what you’re telling them: Don’t feel guilty, don’t second-guess your instincts and don’t waste any time lamenting or worrying about a job that didn’t work out.

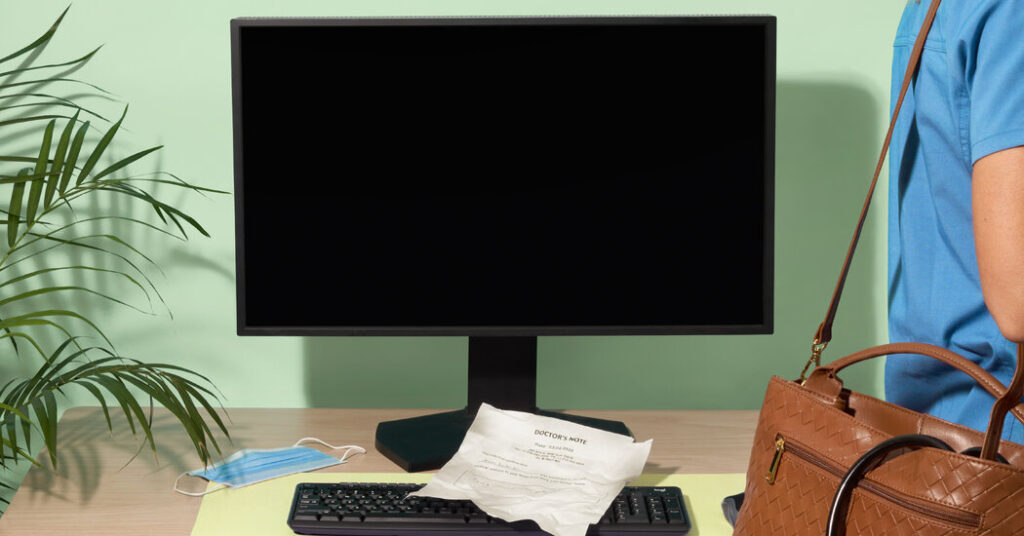

Is Long Covid a Fair Excuse?

Dear Work Friend,

Our medical specialist colleague has for several years claimed long Covid exemptions for working after 5 p.m. and taking overnight on-call commitments at the hospital. Aside from long Covid, my colleague seems fit and well. This exemption has led to grinding yet unspoken resentment.

Our colleague’s “H.R. supported” nonavailability for those non-sociable shifts means that the rest of us have had to bear the brunt of her weekend, evening, overnight and on-call commitments.

Although my colleague agreed to work Christmas Day last year, she called in sick and has since been off on paid sick leave due to “long Covid reactivation.” I suspect that she will use up all her sick leave entitlements before resigning.

This doesn’t seem fair, as our colleague does not appear medically or psychologically incapacitated when she works her regular shifts. What are your thoughts?

For most versions of this question, I might respond with something like “You’re not a medical professional; why are you trying to diagnose your colleague based on casual observation?”

But, well, you are a medical professional, so I suppose I can’t say that.

Even so, I wonder why you’re basing your assessment of your colleague’s condition on the shifts she’s worked out with management as acceptable to her mental and physical state. You say she doesn’t appear medically or psychologically incapacitated when you see her at work. I’d hope so!

That is, indeed, the point of the exemption: So that she can work the shifts for which she is most able. You know that she does her job capably at the times she has agreed with your employer to work. What you don’t know is how she feels or acts in the evenings or at nights, or when asked to perform on short notice.

More to the point, as morally satisfying as it might feel to unmask your colleague as a liar and scammer, the medical reality of her long Covid doesn’t really matter. Her condition is only indirectly the source of your resentment; the extra on-call shifts you and other colleagues have been asked to work are the primary cause. Your sacrifice might feel more noble if you truly believed your colleague were sick. But in terms of hours worked and weekends ruined, it would be the same.

If your colleague uses up all her sick leave and then resigns, all while enjoying medically unnecessary exemptions, would that be “unfair”?

I suppose. But it’s not your money she’s taking, and ultimately, the responsibility for “fair” scheduling falls to management, not to your colleague.

Leadership has allowed the burden to fall unevenly on you and other healthy co-workers without adjusting staffing or compensation; worse, by ignoring glaring scheduling inequities, they’ve cultivated a sense of institutional mistrust. If you can’t trust them to look out for overworked employees, why would you trust the diagnostic procedures by which they distribute medical exemptions?

The point is, management deserves to be the target of your frustration more than your colleague. I say this as a practical matter more than a philosophical one: Complaining about your colleague (or, worse, confronting or accusing her) is unlikely to achieve a materially satisfying outcome. But approaching management to make scheduling more equitable may get you a less frustrating rotation, or a better-compensated one.

“Going to H.R.” is, after all, what your colleague did to secure more favorable hours. Why not do the same, instead of stewing in resentment?

The post Will Leaving My Terrible Job Make Me Look Flaky? appeared first on New York Times.