In the second Trump administration, immigration policy is made with big round numbers. There’s a formula: First the White House sets an ambitious goal—1 million deportations a year, 3,000 immigration arrests a day. Then it presses the federal workforce to meet the target. Last year, Trump officials pledged to double staffing at ICE by adding 10,000 new deportation officers by January 2026. Stephen Miller treated the recruitment drive as a priority on par with the deportation push, demanding daily updates on the pace of hiring. Immigration and Customs Enforcement held job expos in multiple cities and dangled $50,000 bonuses, student-loan forgiveness, and other perks before potential recruits.

Just after New Year’s Day, the Department of Homeland Security declared victory, celebrating an ICE hiring spree that “shattered expectations” and achieved a “120% Manpower Increase.” DHS said it received more than 220,000 applications (many candidates applied for three or four different jobs) and signed up 12,000 new officers, agents, and legal staff in about four months. No federal law-enforcement agency has ever expanded this fast.

The percentage of new deportation officers who are actually ready to go out on the streets, however, is much lower than what the administration has been claiming, according to five DHS and ICE officials I spoke with. About 1,200 recruits have completed courses at ICE’s training academy, and another 3,000 have finished online training courses for new hires with previous policing experience. ICE has also brought back about 800 retirees who can earn a salary on top of their pension. These roughly 5,000 new deportation officers are considered “operational,” and have been given a badge and a gun, though some have yet to deploy due to administrative and logistical reasons. Three of the officials told me they estimate that it will likely take five or six months for the target number of new deportation officers—10,000—to be fully ready.

ICE veterans I’ve spoken with have concerns about the qualifications and aptitude of their new colleagues, especially those with little or no previous law-enforcement experience. Some academy classes have had dropout rates near 50 percent because so many failed the physical fitness requirements. The Trump administration slashed the length of the training course from about five months to 47 days last summer—because Trump is the 47th president, three officials told me at the time—then cut it further. Now it’s 42 days.

[Read: ICE’s ‘athletically allergic’ recruits]

As new employees have started showing up at ICE regional offices around the country, some have been greeted with wariness by veteran officers. “These are people who have no business setting foot into our office,” one senior ICE official told me, describing new recruits who appeared physically unfit for the job and “who would have been weeded out during a normal hiring process.” The DHS and ICE officials I spoke with did so on the condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to reporters.

Tricia McLaughlin, the chief spokesperson for DHS, declined to say how many of ICE’s 12,000 new hires have hit the streets full-time. “We are not going to disclose the specifics for operational security purposes,” McLaughlin wrote to me. She attached a department statement denouncing “mendacious politicians and the mainstream media,” who “continue to smear ICE officers, lying to the American people, and falsely claiming that they are untrained for the job at hand.”

The statement said the 42-day ICE academy course provides training in arrest techniques, conflict management and de-escalation, firearms safety, and proper use of force. I asked one veteran ICE official how much time new hires are spending on de-escalation tactics, especially after the fatal shooting earlier this month of Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis. The principles of de-escalation are sprinkled throughout use-of-force classes and arrest training, the official told me. But he said the amount of time dedicated specifically to de-escalation is about four hours.

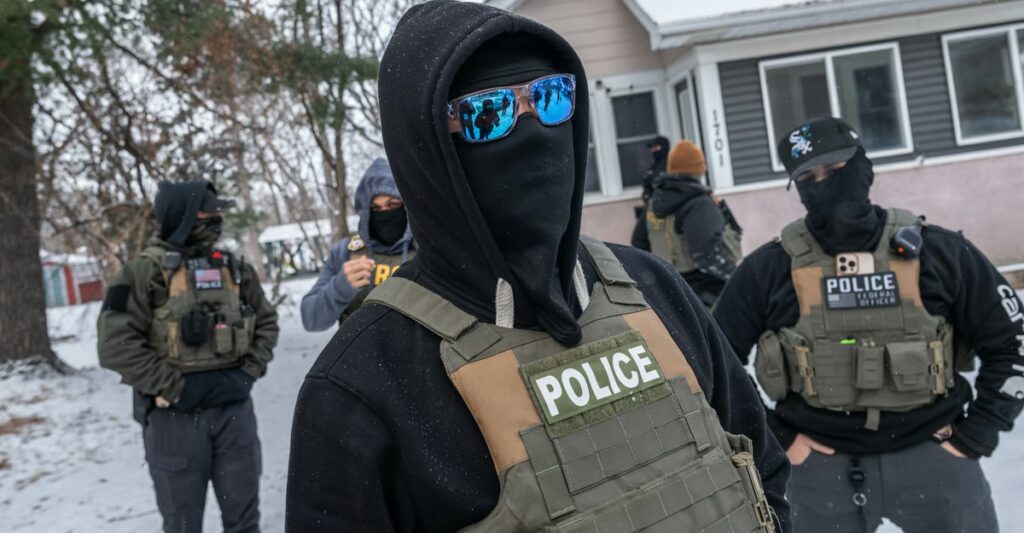

This morning, a 37-year-old man in Minneapolis was fatally shot after a group of federal officers and agents wrestled him to the ground. The circumstances of the killing remain hazy. On social media, DHS officials claimed the man had approached Border Patrol agents with a gun and violently resisted arrest. The department published an image of a 9-mm pistol that it said the man was carrying, and said his death “looks like a situation where an individual wanted to do maximum damage and massacre law enforcement.” Bystander videos that apparently captured the moments leading up to the altercation showed the man, identified as Alex Pretti by The Minnesota Star Tribune, standing in the street and holding up a phone, not a weapon, likely to record the federal forces. In the videos, he makes no attempt to attack authorities. As one agent approaches Pretti, another begins shoving him back toward the sidewalk.

The reporter Laura Jedeed published a first-person account in Slate this month describing how she landed a job offer from ICE last fall, suggesting the agency failed to conduct basic internet research that would show she is a journalist and an outspoken Trump critic. DHS dismissed Jedeed’s account as “a lazy lie” and claimed that she was never offered a position. But Jedeed posted a subsequent video on social media that appeared to show ICE’s hiring portal with her final job offer and an onboarding date at the agency’s New York City field office. “Welcome to ICE,” it said. Jedeed didn’t take the job.

Her story is hardly the only sign that the ICE hiring surge may be cutting corners to achieve the White House’s political objectives. Some ICE regional offices where staffing levels are poised to double don’t have enough desks, body armor, and parking spaces for everyone, agency veterans told me. DHS has emphasized that it will assign new hires to work alongside experienced officers, but those pairings require additional planning at a time when the ICE workforce has been under relentless pressure to ramp up arrests and deportations.

“ICE officers go through a rigorous on-the-job training and mentorship,” DHS said in their statement to me. “New hires take what they learn” from the ICE academy “and apply it to real-life scenarios while on duty, preserving ICE’s reputation as one of the most elite law enforcement agencies not only in the U.S., but the entire world.”

[Read: ’Maybe DHS was a bad idea’]

The ICE staffing surge is crucial to the Trump administration’s bigger goal of 1 million deportations a year. ICE deported about 400,000 people during Trump’s first year in office, well below the president’s target. Trump officials claim more than 2 million people have voluntarily left the United States during the past year— counting them as deportations—even though that figure is based on academic estimates of census surveys.

ICE has an annual budget of about $10 billion, but the agency received three times that much in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act to fund the hiring boom. The bill also provided about $45 billion to expand ICE’s network of detention centers. When Trump took office, about 39,000 detainees were facing deportation in ICE custody. Today there are more than 70,000, and Trump officials want to boost detention capacity to more than 100,000 this year. When I attended an ICE hiring expo outside Dallas last summer, recruiters explained that the state with the highest number of open positions was Louisiana, the operational hub of Trump’s deportation campaign.

The administration also wants more ICE officers on the streets. Trump officials have brought in Border Patrol agents to act as reinforcements in cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago and now Minneapolis. Trump’s rolling campaign has generally targeted one location at a time, but the new hiring surge will give the administration enough personnel to target multiple cities at once.

Trump officials say they are filling the jobs by hiring experienced law-enforcement officers from other federal agencies or state and local police departments. Many of the new hires are anxious about their career prospects at ICE once the burst of one-time funding runs out, officials at ICE and DHS told me, especially if Democrats take control of Congress.

One ICE official I spoke with told me that some of the new hires, especially rehired retirees, are having second thoughts. Hundreds of the returning officers have been ordered to Minnesota, two officials said, where the administration is conducting the largest-ever DHS crackdown. Some officers have been so cold and miserable that they’ve already quit, and ICE officials have held calls to figure out how to deal with the sudden resignations.

Returning officers who have come back from retirement are finding themselves in unfamiliar roles. They spent much of their careers trying to conduct low-key “targeted enforcement” operations in which they planned arrests in advance and sought to take suspects into custody in the safest and least dramatic way possible. Now they’re out in the streets wearing masks, with protesters yelling at them and video cameras rolling. ICE has changed, and the job isn’t the same.

The post Most ICE Recruits Haven’t Deployed Yet appeared first on The Atlantic.