The boys were there for a water balloon fight.

It was an annual tradition to start Carnival celebrations in Barcelona, a working-class coastal city in Venezuela’s east. But only two days after the capture of the nation’s president, Nicolás Maduro, all of their shouting and laughing was not sitting well with the authorities.

Local police officers and National Guard soldiers arrived in force and, according to two of the boys and the relatives of four others, fired shots. The boys and young men — aged 13 to 25 — scattered, but the police arrested 25 of them. Two days later, state prosecutors filed charges.

Their crime? Treason.

“‘I’m going to screw you all over,’” one of the boys, 17, recalled a police officer telling him after his arrest, using an expletive. “‘You all support Donald Trump.’”

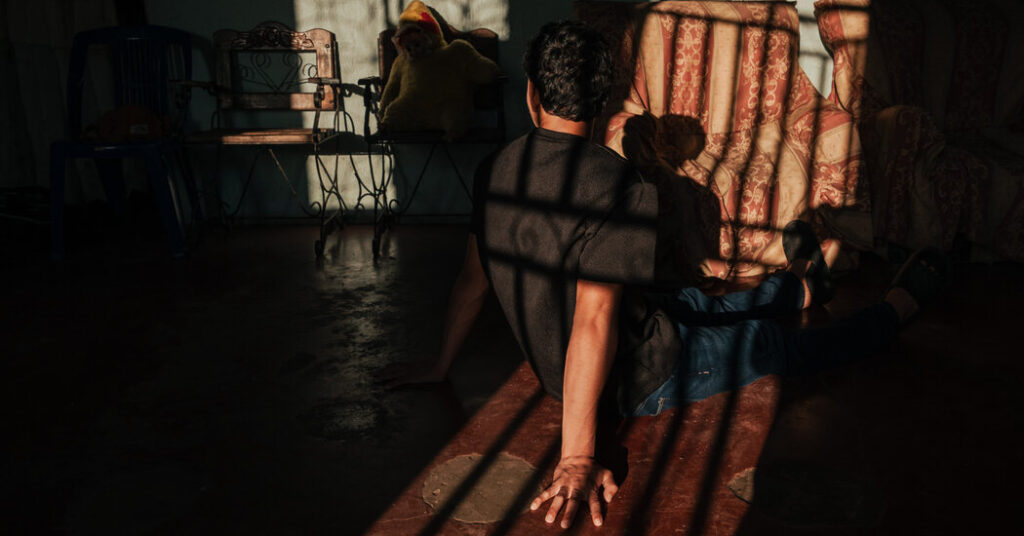

A reporter and photographer from The New York Times this past week visited the neighborhood where most of the detainees live and interviewed two of the boys and seven of their family members. Many of them, as well as other Venezuelans across the country, spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal from the government.

Those interviews revealed that, under the Venezuelan interim government backed by the Trump administration, citizen surveillance and repression are alive and well.

President Trump has praised Venezuela’s interim leadership as highly cooperative, particularly in opening up U.S. access to the country’s oil. Those leaders, who are the same people who helped direct the authoritarian Maduro regime, have also drawn positive headlines for their release of nearly 150 political prisoners, or about a sixth of the nation’s estimated total.

But at the same time, they have quietly added to those ranks, detaining and jailing people suspected of opposing the government, as part of a nationwide campaign to stamp out dissent since the United States captured Mr. Maduro three weeks ago.

Security forces have set up checkpoints on highways, searched citizens’ cellphones, extorted people whose phones contained criticism of the government and arrested dozens of others suspected of celebrating Mr. Maduro’s capture.

“You can be detained simply for traveling the streets. Not in the sense that they put you in prison, but that they stop you and demand your phone,” said Andrés Azpúrua, an internet-freedom activist in Venezuela who tracks government repression. “This has been happening for a long time. But not at these scales.”

The result is that many Venezuelans, while maybe more hopeful since Mr. Maduro’s capture, remain terrified of saying so out loud.

“We know what’s going on, but no one can express an opinion,” said a 49-year-old driver, who lives in the same state as the detained boys. “We want to shout, to celebrate, but we can’t. I want to, but I don’t know where.”

During the interview, the man frequently spoke in a whisper, worried his neighbor might overhear and report him to the police. He added that he leaves his phone behind every time he goes out, fearful the police will search it.

The Venezuelan government did not respond to a request for comment. Diosdado Cabello, the nation’s powerful interior minister who runs much of the state’s intelligence and security forces, acknowledged last week that some officers had extorted citizens.

“I have told the police officers that for anyone who wants to be a policeman, extortion has no place here,” he said, according to a post from his political party.

Venezuelans’ anxiety is driven by years of harsh, systematic repression by the Maduro government. A complex mix of security forces — from military soldiers and police officers, to intelligence agents and masked, armed militias — spied on, threatened, extorted and arrested people perceived to be a potential threat to the regime. Targets included opposition politicians, activists, academics, journalists and even regular people who had simply criticized the government in private conversations.

Over the past two weeks, Venezuelan authorities have slowly been releasing about a sixth of the nation’s nearly 900 political prisoners, according to human-rights groups.

The White House has taken credit. Mr. Trump has also consistently praised Venezuela’s interim leader, Delcy Rodríguez, who was Mr. Maduro’s vice president, while undercutting her rival, María Corina Machado, the exiled opposition leader.

“She’s doing a very good job. We have a very good relationship,” Mr. Trump said of Ms. Rodríguez this past week.

At the same time, Ms. Rodríguez has been overseeing a crackdown at home.

The day Mr. Maduro was captured, Ms. Rodríguez announced a state of emergency in Venezuela that, in effect, gave the government the authority to detain anyone suspected of supporting the U.S. attack. She claimed Mr. Maduro had signed the measure — supposedly as he rushed for safety after the attacks began.

Since then, Venezuelan authorities have arrested at least 31 people and accused them of supporting the U.S. attack, according to an analysis of local news reports. Several were detained for videos they posted on social media.

The most striking case was the arrest of the 25 boys and young men in Barcelona, a midsize city about five hours east of Caracas.

During the recent visit by The Times journalists, the city was on edge. Armed officers at four checkpoints interrogated and sometimes searched passers-by. At sundown in the dense neighborhood where the detainees lived, about a dozen police officers on motorcycles patrolled the streets. The police presence had increased since Mr. Maduro’s capture, according to residents.

The trouble for the neighborhood youth began on Jan. 5. Boys and young men filled water balloons at the bank of the Neverí River and then, according to videos, chased one another around a vacant lot, tossing the balloons and laughing.

When the authorities showed up, the young people thought the arrests would be only temporary to teach them a lesson about causing commotion in the street. But when the police began mentioning Mr. Trump and Mr. Maduro, and then transferred the group to a larger jail, it became clear the situation was more serious.

“We all started crying and asking why, saying that they weren’t criminals, that they were just children playing for Carnival,” said the mother of two detainees, describing the scene of distressed parents outside the jailhouse. “Because the country was in trouble,” the police told her, she added. “And if we knew how the country was, why did we let our children be in the street?”

Fifteen minors in the group were arraigned on several charges including “treason to the homeland,” according to a court document viewed by The Times. Families of the 10 detainees over 18 said they had also been charged with treason.

Families began distributing videos about the teenagers on social media, denouncing their detention. The videos gained traction in the local community, and a week after they were jailed, the authorities released the 15 minors under the condition that they remain in Venezuela and return to court once a month.

But the 10 adult detainees remain imprisoned.

“I haven’t eaten for days,” said Scarlett Ruiz, 24, the sister of one detainee who is 19 and had been preparing to enter college this year. She said the family has been taking him meals and attending court hearings for the past two weeks, watching his condition deteriorate.

“My brother isn’t sleeping. He has bags under his eyes,” Ms. Ruiz said. “They tell them things like, ‘You’re not going to get out of here.’”

María Reyes said she worried about her 21-year-old son in detention because he regularly suffered from epileptic seizures.

And Karen García, the mother of an 18-year-old detainee, said she had not seen her son since Jan. 5. She is confused how her family got wrapped up in the situation. “We’re not political people at all, nor are we interested in giving opinions on that,” she said. “The only thing we want is freedom for our boys.”

Jack Nicas is The Times’s Mexico City bureau chief, leading coverage of Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

The post How a Water Balloon Fight in Venezuela Ended in Charges of Treason appeared first on New York Times.