The fatal shooting of Renee Good by a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officer earlier this month sparked an intense wave of partisan reactions.

Some on the left immediately called to “abolish ICE,” while some on the right insisted that shooting her was justified. It remains unclear, however, how broad and lasting an impact the incident will have among the less politically engaged, who often determine the outcome of elections.

A new poll from The New York Times and Siena University found that President Trump retains majority support on some of his immigration policies but that many voters are concerned about his administration’s immigration tactics, with 63 percent of respondents disapproving of the way ICE is handling its job.

That survey joins more than a dozen polls that have attempted to gauge public opinion about ICE since the incident but that have not provided easy answers as to what the moment might mean when it comes to long-term political consequences. That is because polls are somewhat limited in their ability to accurately measure broad public perception amid politically charged and fast-moving news events.

Here are three reasons for the difficulty:

1. Questions such as whether the shooting was justified are difficult to ask in a balanced way.

It can be hard to ask some questions without affecting respondents’ perceptions of the topic at hand. Results from two polls about the shooting show just how big a role question wording can play.

The first question, asked by RMG Research and the Napolitan News Service, starts by noting that Ms. Good’s death was a “terrible thing,” effectively giving respondents some relief on having to express that view. The question then provides an option for people to say that Ms. Good was “mostly responsible” because she was “threatening toward ICE agents,” or to blame the ICE agent for acting “irresponsibly.” In this poll, the responses were evenly split.

The second question, from CBS News and YouGov, did not offer a similar preamble to the question, and simply asked if the shooting had been justified, resulting in far more respondents saying that it was not justified than saying it was justified.

In both cases, respondents were asked to make a complicated determination in the moment, and the ways in which the question was asked may have heavily influenced the ways in which it was answered. In the first, the pollster could be accused of priming respondents in favor of the ICE agent. In the second, the question of whether the shooting of a woman was justified, absent other information, could create a more sympathetic environment for the person who was shot.

Respondents in both cases could also have been expressing their displeasure with the shooting, or their opinion about the situation in general, which is not what the question asked.

2. Polls reach an overly engaged portion of the population.

Videos showing the incident from multiple perspectives spread quickly. But just how many Americans have watched the videos is a particularly challenging question to answer. Some polls put the number at 70 percent. In one survey that began polling respondents the day after the shooting, 82 percent of voters said they had seen the video.

Two well-known polling phenomena likely pushed results on this question higher than the percentages actually are.

Even the best polls tend to overrepresent people who are politically engaged and who consume a lot of news. While videos of the shooting dominated media coverage in the days that followed, most Americans do not pay particularly close attention to the news.

Higher-quality polls attempt to reduce that bias toward politically engaged respondents using techniques like giving people lots of time to respond to a poll or offering to pay them to complete a survey. But those strategies do not solve the problem entirely, and some of them are impractical for political or news purposes.

As an illustration of how big the gap can be: The New York Times conducted an experiment in 2022 comparing a typical Times/Siena phone poll with a survey in which voters were reached by mail and paid to complete it. Results showed that 58 percent of participants reached by phone said they follow what is happening in government and politics “most of the time,” compared with 42 percent of those reached by mail. Some methods of conducting polls online can result in reaching even more engaged parts of the electorate.

The other phenomenon at play is that people sometimes answer poll questions with what feels like the “right” thing to say, an effect known as social desirability bias. In those situations, the fact that people are being asked about an event or a subject can make them feel as if they are supposed to know about or have an opinion on it.

Evidence that these issues can affect poll questions is well documented. In one instance of such bias, polls conducted immediately after a 2008 presidential debate between John McCain and Barack Obama found that 66 percent of voters said they had watched the event live.

Viewership statistics suggest that the share of voters who watched was actually much lower — around 40 percent.

3. Questions that provoke partisan gut reactions leave out more nuanced views.

It is normal, even expected, for Democrats or Republicans to offer responses that align closely with their partisan beliefs.

But the team mentality that some voters adopt can result in answers that reflect the way they think they should respond rather than what they might actually believe — a phenomenon known to polling researchers as expressive responding or partisan responding. This is a particular concern in instances where respondents are presented with two extreme options, neither of which exactly represents their views.

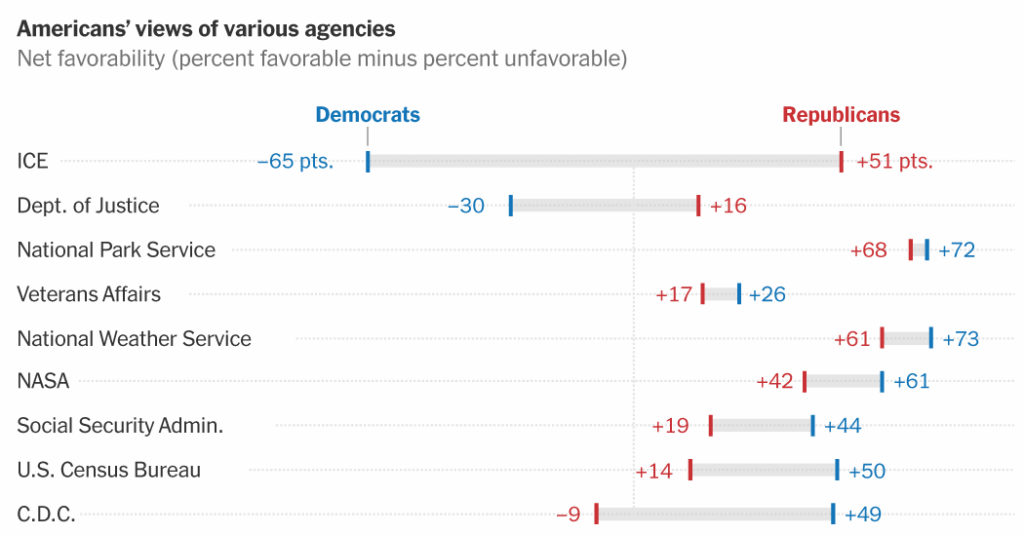

Even before the incident, views about ICE were extremely partisan, priming questions about the agency to be viewed through that already polarized lens.

Take a question like whether to “abolish ICE,” which recent polls have found voters fairly evenly split on. This proposal surely has proponents and detractors. But it also uses partisan language that even some Democratic politicians think might distract voters from the issue at hand. People are asked to choose between two very different options, when their views may fall closer to the middle.

And the question poses a complex test that may be evaluated differently by different people: Does “abolish ICE” mean getting rid of immigration enforcement altogether, or giving that role to a different agency? The Democratic-leaning polling firm Data for Progress explored several different interpretations of the phrase and found that voters were split on what it meant.

One method of reducing the risk of expressive response is to ask questions that make the decision clear and that only ask the respondent to consider one thing at a time. Offering middle-ground options on a divisive topic is also another way to address this. In polls that offered alternative solutions, like reducing funding for ICE, people have responded with much higher bipartisan support to reform the agency.

Additional research contributed by Alex Lemonides and Caroline Soler.

Christine Zhang is a Times reporter specializing in graphics and data journalism.

The post Why Polls About the Killing of Renee Good Are So Hard to Parse appeared first on New York Times.