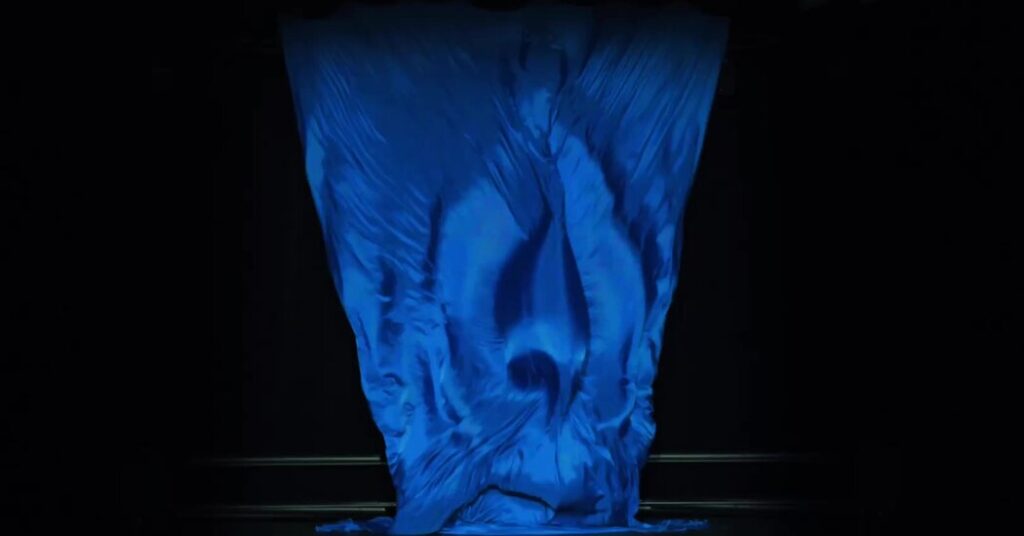

Over 2,100 yards of blue, white and gold silk cascaded from the ceiling of the Grand Theater of the City of Luxembourg recently, flowing to the floor like a waterfall. Performers thrashed underneath a vast silken sheet that looked like a stormy sea. Cannons shot balls of the lustrous fabric that unfurled midair before landing to leave the stage covered in multicolored ribbons.

This was “Inhale Delirium Exhale,” a show by the Belgian theater artist Miet Warlop, in which performers manipulate almost four miles of silk onstage.

Warlop’s visual extravaganza has been wowing audiences on a tour across Europe since May. But the artist said in an interview that there was much more to her performances than mere spectacle. “Inhale Delirium Exhale,” she said, was an attempt to represent onstage the mental processes at work when we struggle to cope with personal anxieties or world events.

Such pressures sometimes envelop us like the silk does the performers, said Warlop, 47. At other times, we take control of our worries, just as the artists onstage tame the silk by gathering the fabric into piles.

It may be a “super visual” show, Warlop said, as many critics have noted. But, in the end, she said “you’ve got to feel emotion.”

“Inhale Delirium Exhale” still has dates ahead in cities like Madrid; Porto, Portugal; and Nantes, France; and Warlop will also tour two other shows — “After All Springville” and “One Song” — around Europe this spring.

Her unique visual and performance style will come to even wider attention when she represents Belgium at this year’s Venice Biennale, an honor usually reserved for artists who present their work in galleries rather than theaters.

In Venice, Warlop will present a performance called “IT NEVER SSST,” in which singers and musicians will ritualistically move and destroy plaster casts of words. The jury that chose Warlop said in a statement that the high-octane performance would have a “rock ‘n’ roll spirit” and capture “the chaotic state of the world in a real and visceral way.”

This looks set to be a banner year for Warlop, who has walked a decades-long route to success.

The daughter of an art therapist mother and an accountant father, Warlop grew up in Torhout, a town in western Belgium. She studied art at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent, where her teachers pushed her to experiment with different media rather focus on painting or sculpture.

For her graduation project in 2003, Warlop staged a series of scenes with actors, including one in which a woman cried continually while sitting on a huge pile of used tissues. Although she had created it for a fine arts course, it won a Belgian theater prize, and soon Warlop was staging similarly innovative, sometimes surreal, works across Europe.

Milo Rau, a Swiss theater director who commissioned several works from Warlop when he ran the NTGent playhouse in Belgium, said that Warlop’s visual style made avant-garde ideas appeal to a wide variety of theatergoers — whether “children of 6 or someone in their 80s.”

That was true of “One Song,” Rau said, a piece that he commissioned from Warlop that went on to be a breakout production at the 2022 Avignon Festival. In that show, musicians in sports gear exercised while performing a song about grief. The band’s singer ran on a treadmill; the violinist played while walking precariously along a balance beam; the double bassist did ab crunches as he plucked. Behind them, a group of performers, dressed as rabid fans, cheered and booed.

“One Song” received ecstatic reviews that often focused on the high-energy performances. Writing in The New York Times, the critic Laura Cappelle called “One Song” “loud, preposterous and extremely entertaining.”

But Warlop said there was something deeper under the showy surface. It was a response to the death of her brother by suicide, she said, that argued that society, like a sports team, was united by losing rather than winning.

When she turned to theme of inner turmoil for “Inhale Delirium Exhale,” Warlop said, she had been thinking about Baroque paintings that use billowing cloth “as a metaphor for the turbulence of time,” as well as images from old movies of women walking on the beach in billowing silky dresses.

“Let’s take this lame thing — this drapage, this covering the body with silk — and try to make it something mental,” Warlop recalled thinking.

Realizing that ambition, however, proved a challenge.

Her budget didn’t stretch to buying miles of expensive fabric, so she first persuaded Hermès, the luxury fashion brand famous for its silk scarves, to send her some of its unused material. The rolls that arrived were about 35 inches wide, so Warlop and a team stitched them together to make huge flags and sheets.

As she then tried to create scenes with the material, Warlop said, she realized that silk “falls to the floor in one second,” so she had to develop ways to keep it moving in the air. In the final 50-minute show, six performers and four offstage technicians suspend the silk from lighting rigs and animate it with wind machines and other devices so that the fabric is in constant motion.

Even after the show’s premiere, Warlop said, its development wasn’t over. When her team first used the cannons to shoot balls of silk into the air with weights attached to make them unfurl, some flew dangerously close to the audience and she had to alter the scene. On a later tour stop, theater administrators worried because the silk was flammable, so she and her team had to unstitch all the cloth, get it treated with flame retardant and put it back together.

Warlop’s spectacles are always visually stunning, but they are also a chance to consider big questions, she said: “Why are we so lonely? Why are we afraid? How can we find each other? How can we have joy?”

Searching for those answers doesn’t have to look dull, she added: “Why would we make work if it was boring?”

Alex Marshall is a Times reporter covering European culture. He is based in London.

The post Turning 4 Miles of Silk Into a Stunning Theater Spectacle appeared first on New York Times.