Sohrab Ahmari is the U.S. editor of UnHerd.

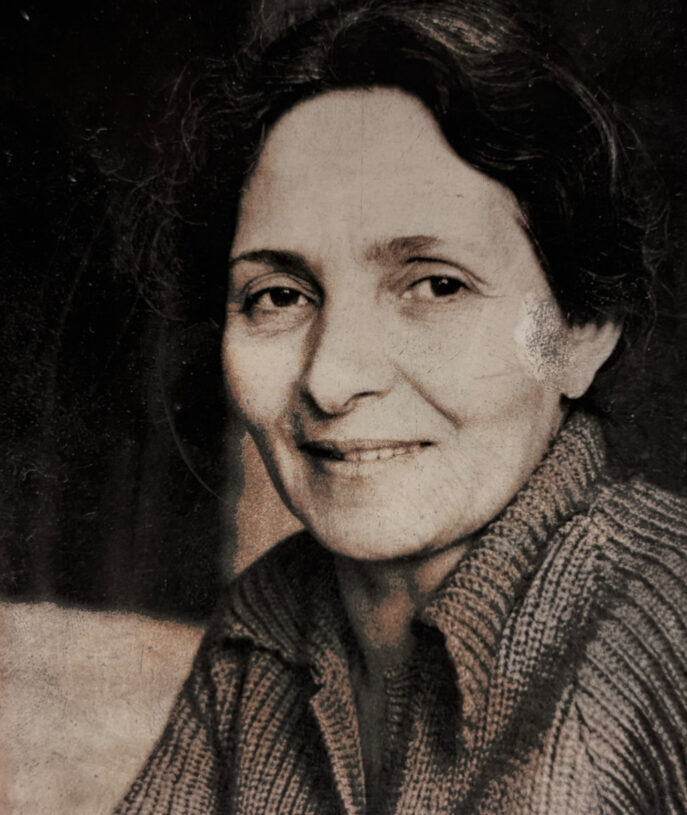

All the grown-ups smoked Western cigarettes, but not my great-grandmother Homa-joon. Hers were thinner and shorter, giving off a sweet, musky smoke that filled her room in the house my grandparents and parents also shared for most of my childhood in Tehran. Homa-joon preferred them not because the brand bore her name — Homa cigarettes — but because they were made in Iran.

She was born in the aftermath of Iran’s 1905 Constitutional Revolution, when a dying Qajar dynasty grudgingly granted an elected parliament in response to the popular demand that government be mashrut, or “conditional” on the consent of the governed. Homa-joon’s father and husband were active in the mashruteh movement, bent on launching Iran, a dilapidated former empire, into sovereign dignity.

The Islamic Republic is in retreat on nearly every front. Its nuclear program lies in rubble after last summer’s U.S. bombing raid. Since the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas terrorist attack in southern Israel, the Jewish state has degraded the ring of Iranian proxies that used to reach from the Levant to the Arabian Peninsula. And at home, the Tehran regime struggles to uphold Islamic morality norms, including the mandatory veil for women once systematically enforced on pain of flogging or worse.

For many Iranians — including those, like me, who are part of the diaspora — the moment is bittersweet. We can cheer the unraveling of a cruel and irrational order under the weight of its internal contradictions and external hubris. The reflection turns bitter, however, when we look to the likes of Turkey, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Iranians haughtily view such nations as their civilizational inferiors, yet they are the countries pulling ahead, achieving prosperity, stability — or at the very least, normality.

Meanwhile, despite its civilizational pedigree, Iran today is poor, repressive, dysfunctional, corrupt and suffering one of the world’s most severe cases of brain drain, which reached record highs in 2024.

What happened? Why do Iranians have so little to show for mounting one of the last revolutions of the modern era? And what aspects of the country’s national character explain how it ended up wasting 50 years?

The answer lies, in part, in the absolutism of Iranian political culture and statecraft. A yearning for purity drives the country toward passionate idealism. When disappointed, it spreads passivity, cynicism and venality. Unchecked, this tendency threatens whatever order is destined to succeed rule by the ayatollah.

To understand the purity obsession, it helps to return to Iran at the dawn of modernity, during the battles for Majlis and constitution that defined my great-grandmother’s early life.

A precursor of those battles came in 1890, when the Qajar shah granted a British firm a 50-year monopoly over the production and sale of tobacco in Iran. The firm expected to draw at least 500,000 pounds a year after kicking back 15,000 pounds and one-quarter of the profits to the palace.

Such lopsided arrangements were not uncommon among Western concessionaires, who dominated many early industries (and natural resources) in Iran. But the tobacco deal proved intolerable to the populace once its terms became public, especially since the Ottoman Turks had attained far better terms in a similar arrangement.

A then-nascent nationalism had found a concrete target for its ire. The movement blended religious conviction with democratic and progressive ideas imbibed from the West. Above all, it was animated by a dawning sense of shame: A people who viewed themselves as the fulcrum of the world hadn’t just fallen behind, they were now in thrall to foreigners.

A dissident Iranian newspaper published in London enumerated the nationalists’ complaints in 1890, the year of the concession: the nation’s “army was the laughingstock of the world,” its “princes deserving the pity of beggars … our towns each a metropolis of dirt … our roads worse than the tracks of animals … our mujtahids [religious scholars] craving the justice of the unbelievers.”

Shiite religious scholars turned popular anger at the tobacco concession into collective action. The era’s supreme ayatollah, Mirza Shirazi, issued an edict banning smoking until the shah agreed to revoke the concession. In a matter of days, Iran — a nation that, as a contemporary British historian quipped, would sooner give up bread than tobacco — stopped using tobacco; even the women in the shah’s harem wouldn’t touch their water pipes.

Soon placards threatened the lives of all foreigners. This nationalist anger was an understandable response to the frittering away of national rights that stains the Qajar legacy to this day. But public rage also erupted because, as a French historian wrote at the time, Iranians “will never reconcile themselves to the idea that their tobacco should pass through the hands of Christians, who, in their eyes, render impure what they touch.”

No economic justification — that the deal would cut out the middlemen, for one — could overcome the horror of this impurity. Ultimately the concession was withdrawn in 1892. And my great-grandmother, who lived within memory of these events, never strayed from domestic cigarettes.

Her father, known as Mir Abdolrazzaq, was the owner of a print shop and a fierce nationalist.

After the 1905 uprising established a parliament, Mir Abdolrazzaq designed the emblem at its entrance: “Adl Mozzafar” — literally “justice triumphant,” and a reference to Mozaffar ad-Din Shah, the Qajar monarch who granted a measure of democracy.

Mir Abdolrazzaq was assassinated by a rival group of constitutional nationalists. His killing reflected the sheer bedlam that broke out after the 1905 revolution, owing in part to the ferocious opposition to Iranian democracy from Britain and especially Russia, whose troops at one point bombarded the Majlis, Iran’s parliament.

The disorder was also a consequence of bitter divisions among the constitutionalists themselves, each camp insisting absolutely on its own vision for the future and brooking no dissent. As Oxford historian Homa Katouzian notes, it became commonplace to say that an area had become “constitutionalized,” when one meant that it had fallen into chaos.

After Mir Abdolrazzaq had been killed, one of his comrades, Ebrahim Ziae, married his teenage daughter, my Homa-joon. Ziae would go on to establish a nationalist newspaper, Iran-e-Azad (“Free Iran”). He was also elected to the Majlis three times from his native Fars province in southern Iran.

Iran’s salvation would come not through democracy, but from the ambition of a Cossack officer called Reza Khan, who would crown himself Reza Shah, founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, which, including his son’s tenure, ruled the country from 1925 to 1979.

An Atatürk-like figure, Reza Shah set out to modernize Iran from on high, and succeeded to an astonishing degree. He paved roads, established a public school system, built factories and summoned a modern civil service — projects quickened by the burgeoning flow of oil revenue from the Persian Gulf.

My politically enfeebled great-grandfather Ebrahim Ziae, who regarded Reza Shah as a dictator, founded an unprofitable grocery co-op in Tehran. Customers received pamphlets on constitutionalism along with their herbs and cheese, a gesture of resistance that did little more than amuse them.

And yet Reza Shah wasn’t without effective opponents. Most notable was Mohammed Mossadegh, the son of a Qajar revenue officer distinguished for his aversion to corruption in a country where graft was (and still is) a way of life. Mossadegh was wary of Reza Shah’s modernization plans. For him, the most noble goal was total independence — the same impulse toward purity that had impelled an earlier generation of reformers to resist foreign technical and economic influence.

“What would happen if the roads were not paved and the buildings and guesthouses went unbuilt?” Mossadegh asked in a famous essay published not long after Reza Shah’s takeover. “I wanted to walk over the earth and not suffer my country to be taken over by others.”

After the Allies deposed Reza Shah for his flirtations with the Axis powers, Mossadegh amassed influence as a parliamentarian, a minister and eventually prime minister under Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, Reza’s son and successor. Much as Qajar-era nationalists had sought to cleanse Iran’s vice economy of a predatory foreign presence, Mossadegh moved to overturn the concession that allowed the British Exchequer to claim the lion’s share of profits from Iran’s oil reserves.

Nationalizing Iran’s oil would push the country to the brink of economic ruin. Iran lacked the capacity to extract, refine, market or distribute its oil independently. A British-led embargo soon followed, later backed by Washington, and Mossadegh was ultimately overthrown in a 1953 coup supported by the CIA and MI6. A plausible revisionist view holds that by ruling through emergency decrees and alienating a broad swath of Iranian society, Mossadegh may have fallen even without U.S. intervention.

Mossadegh’s absolutism — his lack of prudence and practical wisdom in the teeth of geopolitical threats — set back the cause of independence. And of democracy.

The yearning for purity that fuels Iranian political culture peaked with the 1979 Islamic Revolution. An early harbinger was the removal from the Majlis entrance of the emblem designed by my great-great-grandfather, a relic of what the new Islamist regime denounced as 2,500 years of monarchic decadence — a past it was determined to wipe out in its fanatical early years.

Much else had to be effaced to purify Shiite Iran: Renaissance nudes in art books at the university where my mother studied painting; pre-Islamic symbols and place names deemed pagan or nationalist; whole genres of music, cinema and mixed-gender social life, all of which were seen as corrupting imports from the West.

In this sense, the 1979 revolution, for all its appeals to religious tradition, was fundamentally a modernist project: It sought to fabricate, for the needs of the present, a pure past that had never existed.

Had Iran’s purifying ambitions remained within its own borders, the Islamic Republic might not find itself in such a precarious position today. Instead, the Islamists also set out to cleanse the wider Middle East of what they deemed “pollutants” — the Jewish state, the United States and Arab regimes judged guilty of accommodating both.

The Islamic Republic, moreover, pursued regional purification with the same indifference to the balance of power that had marked Mossadegh’s quest to nationalize oil. Its leaders chanted “Death to Israel” at a nuclear-armed state, and “Death to America” at the global hegemon, while fielding an air force largely frozen in the 1970s. A Persian bluff, you might call it, but even the boldest bluffs are eventually called.

By contrast, comparable powers in the region, such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey, sheltered their aspirations for development and independence within the reality principle — and under Western alliances, even tutelage. The citizens of these countries today enjoy rising living standards, relative security and passports that open access to many international destinations (passports from Turkey and Saudi Arabia allow travelers to visit 113 and 88 countries, respectively; for Iran, it’s 40).

It remains to be seen whether the next generation of Iranian leaders, whether emerging within the Islamic Republic or from outside its borders, can pursue a more realistic politics unburdened by the pipe dream of purification.

Some of the current regime’s opponents speak openly online of executing regime officers and “collaborators.” Such rhetoric can only make mass defections and a peaceful transition less likely: Why would a midranking member of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps side with dissidents if he knows the next regime will threaten his life and his family?

Likewise, it’s not uncommon to encounter talk of extirpating Islam as a foreign “Arab” imposition. How would they go about doing so? Banning the veil? Razing mosques? The impulse is perhaps understandable after nearly 50 years of theocratic repression. Yet Islam has been part of the warp and weft of Iranian civilization for the better part of two millennia. Ripping out the Islamic thread and restoring some pre-Islamic “purity” is an ambition as dangerous and farcical as the Islamic Republic’s own drive to erase Western and pre-Islamic influences from the Iranian mind.

For now, Iran’s young dissidents are lighting cigarettes with burning photographs of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. They’re definitely Western brands.

The post The curse of purity in Iranian politics appeared first on Washington Post.