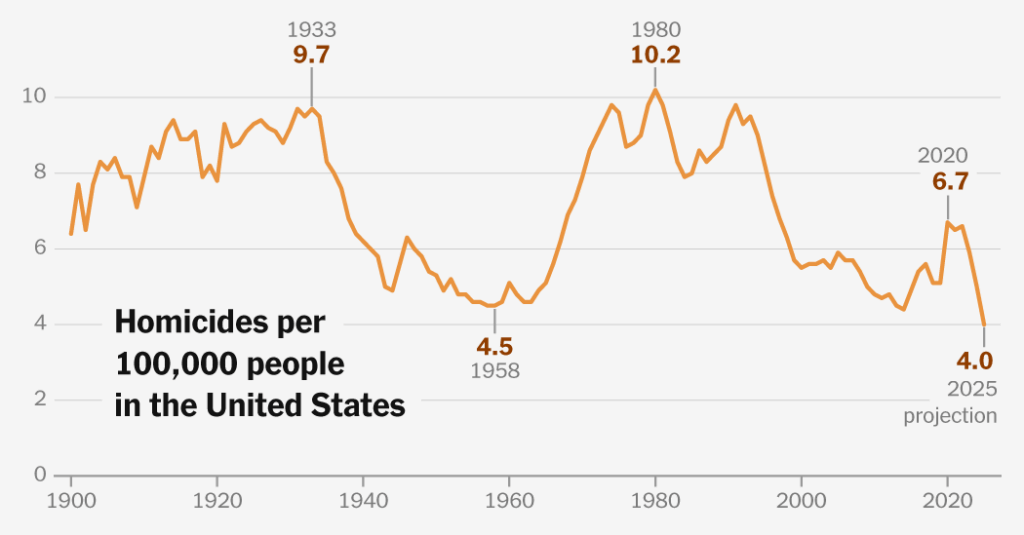

Last year will likely register the lowest national homicide rate in 125 years and the largest single-year drop on record, according to a new analysis of 2025 crime data.

Violence has been falling for several years. But last year for the first time, all seven categories of violent crime tracked by the analysis fell below prepandemic levels. The numbers provide further evidence that the surge in violence in the early 2020s was a departure during a time of massive social upheaval, not a new normal.

The analysis of data from 40 cities, by the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan think tank, found across-the-board decreases in crime last year compared to 2019: 25 percent fewer homicides, 13 percent fewer shootings and 29 percent fewer carjackings. Between 2024 and 2025, only drug crimes went in the wrong direction, but they were still lower than in 2019.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation has not yet released nationwide crime data for all of 2025, but statistics published by cities and collected by independent researchers are already telling the latest chapter of a remarkable story. In just half a decade, cities have gone from upswings in murder and mayhem the likes of which some had not seen in 25 years to declines themselves worthy of headlines.

The spikes began in 2020 with the shock of the global pandemic and, just a few months later, sweeping protests over police killings, both of which strained the capacity of law enforcement.

The Council on Criminal Justice used available F.B.I. data, which goes through September of last year, and other sources to estimate what the final nationwide homicide rate will be. Analysts also collected data from cities, ranging in size from 180,000 residents (Cary, N.C.) to 8.3 million (New York), to look at other categories. Not all cities reported numbers for every crime.

In many cities, the declines were staggering. Baltimore, which had high homicide numbers before Covid-19 hit, had a decrease of 60 percent, hitting a record low last year. Salt Lake City, Chattanooga and El Paso — three very different cities with populations under 1 million — each saw their homicide rate cut roughly in half between 2019 and 2025.

Of the 35 cities whose homicide rates were in the analysis, all but eight had a lower murder rate in 2025 than before the pandemic. Those whose murder rates were still the most elevated included Milwaukee, at 42 percent higher; Austin, at 36 percent higher; and Minneapolis, at 30 percent higher.

Still, both Austin and Minneapolis appeared headed in the right direction, with steep declines in their homicide rates from 2024 to 2025.

Even the public is starting to believe that things are improving. Typically, most people insist that crime is going up regardless of the data. But in its annual crime survey last October, Gallup found that only 49 percent of respondents said crime was worse than the year before, compared to 64 percent in 2024. The percentage of people who said crime in their own neighborhood was an “extremely serious” or “very serious” issue, and the percentage afraid to walk alone at night, had also declined.

The numbers have been at the center of heated political debate since President Trump returned to office, after he campaigned on fears of a migrant-led crime wave and complained of “bloodshed” and “chaos” in Democrat-led cities.

Though crime was already declining before he took office, Mr. Trump has credited tactics such as sending in National Guard troops with extinguishing crime in Washington. And he has said that federal action has made other cities like Minneapolis, where immigration officers are conducting what they say is the largest immigration enforcement operation in history, safer.

“ICE is removing some of the most violent criminals in the World from our Country,” Mr. Trump wrote on Truth Social earlier this week.

Crime decreased more sharply in Washington as federal officers and National Guard troops gathered in the city, dampening pedestrian traffic and other activity.

Still, a New York Times examination found that only 7 percent of immigration detainees had a prior conviction for any violent offense. And many Democratic state and local leaders, most recently Mayor Jacob Frey of Minneapolis and Governor Mike Walz of Minnesota, have called the federal officers themselves, one of whom shot and killed a protester in her car, a threat to public safety.

Experts said there is little to justify any claim that President Trump is responsible for last year’s drop in crime.

“There are many more cities that didn’t have the National Guard that saw their crime go down than cities who had the National Guard who saw their crime go down,” said Alex Piquero, who served as head of the Bureau of Justice Statistics during the Biden administration and now teaches criminology at the University of Miami.

In fact, researchers have long struggled to explain why crime fluctuates. Research has credited policing strategies and incarceration rates, mental health treatment and gun laws, the beautification of vacant lots and the phasing out of lead, which impairs brain development, from gasoline in the 1970s. Improvements in life-saving medical care have also reduced the homicide rate (though the new study finds that assaults also declined, by 6 percent since 2019.)

Charles Fain Lehman, a senior fellow at the Policing and Public Safety Initiative of the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank, pointed to changes like the aging of America, increased obesity, and the ubiquity of surveillance through security and cellphone cameras. “Basically the structural factors in society are pushing us towards less crime,” he said.

Emily Owens, a University of California, Irvine professor who studies how policy affects crime, said that while violence was declining, the number of people reporting that they were victims of cybercrime had soared, causing her to wonder if crime that used to happen on the street was moving online.

“The way that people interact with each other has been changing dramatically and becoming much less face-to-face, which is sort of a requirement for violence, right?” she said.

Still, criminologists do not wholly discount the value of the multipronged effort that many cities mounted against violence in the past few years, including hot-spot policing, summer jobs for youth, cognitive behavioral therapy and focused deterrence, an approach that calls for paying sustained attention to the small number of people at highest risk of committing violence.

“Cities and states were really throwing everything they had at figuring out how to stop it,” said Jennifer Doleac, who leads criminal justice research at Arnold Ventures, a philanthropic foundation.

“The question is how do we harness that energy to keep it going, like don’t take our foot off the gas,” she said. “We do have control over our destiny here.”

Zach Levitt contributed reporting.

Shaila Dewan covers criminal justice — policing, courts and prisons — across the country. She has been a journalist for 25 years.

The post The American Murder Rate Has Never Been Lower, a New Report Projects appeared first on New York Times.