If you’ve heard of my people, the Rohingya, it is probably as faraway, faceless victims of violence, displacement and possible genocide — a people defined by their suffering.

Yes, we are in crisis. We are a predominantly Muslim minority from western Myanmar that has been persecuted for decades. In 2017, the country’s military began a campaign that drove hundreds of thousands of us across the border into Bangladesh, where a generation of Rohingya is growing up in refugee camps with no end in sight.

Global indifference prolongs our plight. Humanitarian crises from Gaza to Ukraine to Sudan are debated, condemned and covered extensively by the media. Yet if the Rohingya are noticed at all, it is as part of a distant “forgotten” crisis — not as the people living within it.

But we are not just victims. We are a people with our own long, distinctive history, defined by faith, resilience and a determination to shape our future — a people worth fighting for.

At last, there is a sliver of hope for us.

This month, the International Court of Justice opened hearings in The Hague on whether Myanmar committed genocide against the Rohingya — which the country denies — finally opening a potential path toward recognition of what we’ve endured and accountability. The first full genocide case brought before the court in more than a decade, it will also set a wider precedent for how an increasingly conflict-ridden world responds to large-scale violence and impunity.

But for the Rohingya, real change could take years — time we don’t have as cuts in aid by the United States and other countries bring new hardships.

The refusal to see the Rohingya begins in predominantly Buddhist Myanmar itself, where the military junta denies that we have a place. This ignores the fact that for centuries our home has been Myanmar’s Rakhine State — a coastal crossroads between South Asia and Southeast Asia, where Buddhist and Muslim communities lived alongside each other long before colonial borders were drawn.

Generations of Rohingya have grown up under constant fear — when my mother wanted me to stop crying she would say the words sure to quiet any Rohingya child: “The military is coming.”

In August 2017, when I was 14, we hid at home for days as the sound of gunfire rang out in our village. The army was attacking again. My parents decided that we should flee for our lives. I haven’t seen my home since.

Along with thousands of others driven from their homes, we walked for a week, crossing mountains on waterlogged roads during the rainy season, to Bangladesh. We ended up in the vast refugee camps at Cox’s Bazar, where more than a million Rohingya live and where I spent the next six years in a shelter made of bamboo and tarp.

We lived with mosquitoes and frogs; floods that swept away our shelters; chilly winters and sweltering summers. We had no formal schools or jobs. Every day more Rohingya streamed in. Yet we’ve clung to who we are. Neighbors shared what little they had, drawing on traditions of village kinship and generosity. We women drew flowers or wrote our names on our hands with henna during the Eid holidays. Children all around us played games. And my mother planted banana trees that seemed to embody our will to survive and grow.

I taught myself English by downloading YouTube videos of Ellen DeGeneres’ talk show and by 15 was helping visiting delegations, humanitarian activists and journalists who needed a translator. A year later I enrolled in college in the Bangladeshi city of Chattogram and regularly traveled back to the camp — six hours by bus — to visit my family and persuade other Rohingya parents to send their girls to school. They often resisted, fearing their daughters might be targeted for being Rohingya, or because education felt meaningless in the camps. I told them how it had transformed my life. Many parents changed their minds, and their girls are now studying.

Everything changed for me in 2022 when my family was selected for resettlement in the United States under a State Department program launched during the Biden administration. In December of that year we arrived in Chicago — the hometown of my role model Michelle Obama — to start a new life.

Americans have welcomed us with kindness. We speak Rohingya at home and eat spicy Burmese food as the snow falls outside. We are thousands of miles from Rakhine, but we are holding on tight to our language, customs and memories of a distant home that we hope to return to someday.

More than one million refugees remain in these camps. Some of my friends have had children there. I visited the camps twice in recent years. Children asked me the same questions I once asked: Why are we still here? When can I go to school? When can we go home? I had no answers, and it broke my heart.

Time is running out for the Rohingya as the U.S. cuts in foreign aid cascade through the global effort to help us, though the Trump administration has subsequently pledged to continue providing targeted support.

The U.N.’s response program is far short of its financial targets, the World Food Program has warned that funding constraints threaten its ability to provide food aid, raising the risk of increasing hunger and malnutrition, and last year thousands of schools in the camps had to shut down, affecting more than 200,000 Rohingya children. Bangladesh’s government has said that it, too, is running out of resources to help the Rohingya, and has called for urgent international action. The U.N.’s refugee agency and aid groups have warned that worsening conditions in Myanmar and Bangladesh have driven desperate refugees to undertake dangerous sea journeys to neighboring countries.

If the International Court of Justice rules that genocide occurred, it could strengthen global pressure on Myanmar to prevent further genocidal acts and make it harder for countries to continue to trade with or otherwise engage with the junta.

But a ruling could take months, or longer. In the meantime, Rohingya exile and dispossession will continue without sustained international support. We may be stateless and marginalized, but we know who we are. The world needs to see us, too.

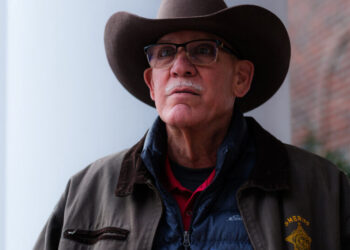

Lucky Karim is a Rohingya human rights advocate, founder of Refugee Women for Peace and Justice, and a Refugees International alumni fellow.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post My Rohingya People Are Running Out of Time appeared first on New York Times.