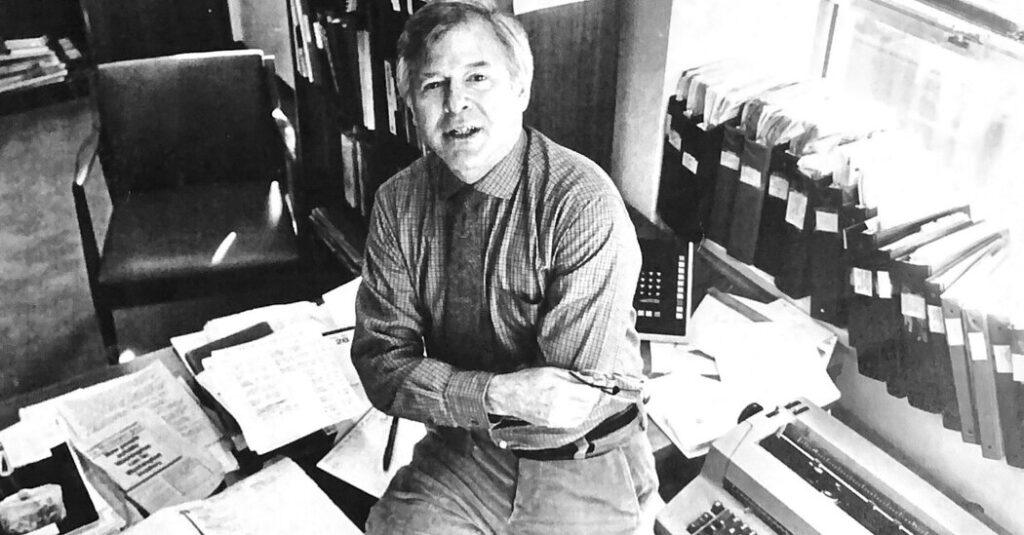

Stephen H. Hess, a Washington insider who advised presidents, wrote books on government and the media, and for five decades was an oft-quoted academic news source at what is sometimes called “the other government,” the Brookings Institution, died on Sunday at his home in Washington. He was 92.

His son James said the cause was prostate cancer.

Two weeks before the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama halted his Democratic campaign for 36 hours to fly to Hawaii to visit his gravely ill 85-year-old maternal grandmother, Madelyn Dunham, who had raised him from age 10 until he went away to college. Historians called it an unusual and risky step for a candidate to take a timeout that close to Election Day.

“They say he’s too mechanical, he’s cool — and here he does something terribly human,” Mr. Hess told The New York Times that day. “This isn’t planned by his strategist. He made the case in his book that she is very important to him. You can turn it around and ask, ‘What if he didn’t go?’ It’s an awful thing to say — but it’s a political plus. People in Ohio have grandmothers, too.”

In his heyday, Mr. Hess was one of the most widely quoted political scientists in Washington, not least because he specialized in the high-profile subjects of the presidency, public policy and the press. He was on the Rolodex of nearly every reporter in town, and with good reason. With official statements often self-serving, he was an independent and influential analyst with solid credentials.

He had been a White House speechwriter for President Dwight D. Eisenhower and an urban affairs adviser for President Richard M. Nixon. He had counseled President Gerald R. Ford, worked for President-elect Jimmy Carter and President Ronald Reagan, and had helped orchestrate President Bill Clinton’s appointment of Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Concurrently, Mr. Hess taught media and public affairs at George Washington University (2004-9) and government studies at Harvard (1979-82), and lectured at 50 colleges and universities. He was the United States representative to the United Nations General Assembly (1976) and chairman of the White House Conference on Children and Youth (1969-71). And he advised the Ford and Russell Sage foundations, two of the country’s venerable private philanthropies.

Mr. Hess wrote or co-wrote more than 20 books on public policy, the press and the pillars of democracy, including volumes on political cartoons that shaped the national identity. He also wrote a memoir, “Bit Player: My Life with Presidents and Ideas” (2018), which detailed his behind-the-scenes roles in the failures and achievements of successive administrations.

Since 1972, Mr. Hess had been a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, an officially nonpartisan Washington research organization whose forerunner was founded in 1916 by Robert S. Brookings, a St. Louis manufacturer who was appalled by the gulf he had found between academic expertise and the federal bureaucracy. His institute became a center of learning with a voice independent of the government.

Like a university without students, Brookings harbors a cadre of gifted scholars, called fellows, whose public-policy books, though not best sellers, are read by intellectual leaders and in corridors of power. Perhaps the nation’s most prestigious think tank, Brookings helped President Franklin D. Roosevelt understand the causes of and possible remedies for the Great Depression as well as mobilize for World War II and plan for the postwar global recovery.

Mr. Hess was a go-to source for hundreds of reporters on countless subjects, from analyses of election races to nuances in the clandestine arts of leaking. He enumerated differences between the goals and advantages of presidents in their first year in office as opposed to their second year, when the ideas and talent fade, and explained why second terms are almost always worse, if not disastrous.

He called himself a conservative and worked for Republicans early in his career. But he later signed on with Democrats and liberals and discussed all sides of political fights in his books. In a city of many think tanks on both the ideological right and left wings, he was regarded as an academic who used statistical evidence and interviews to support his conclusions.

In his book “The Washington Reporters” (1981), for example, Mr. Hess assembled a statistical profile of 1,250 reporters from newspapers, magazines, news agencies and television and radio outlets. He detailed the ways they worked and their journalistic preferences and dislikes. It was not always a flattering picture.

“While reporters agree that regulatory agencies are not sufficiently covered, they do not want the assignment,” he wrote. “Heavy reliance on documents makes the beat ‘dull,’ ‘boring,’ ‘drudgery’ — words that are repeated over and over.”

Indeed, he found, Washington reporting is overwhelmingly anecdotal, with reporters relying on documents in only one-fourth of their articles. Moreover, those “documents” are often just press clippings.

“Given that most copy is produced under deadline conditions and other hardships,” Mr. Hess wrote, “research that rests heavily on other newspaper stories bears a high potential for perpetuating error.”

In a companion study, “The Government/Press Connection: Press Officers and Their Offices” (1984), he spent more than a year observing press offices at the White House, the State, Defense and Transportation departments, and the Food and Drug Administration.

He found a group of hardworking, productive press officers, whose work could be denigrated by reporters, patronized by bureaucrats and undervalued by their bosses, who often barred them from inner councils, giving them insufficient information to properly inform the news reporters dependent on them. He wrote that the most serious charge against the press officers — that they manage, manipulate or control the news — was unfair.

In “The Art of Leaking,” a 2010 article in the journal Foreign Policy, Mr. Hess discussed the tricks of Washington’s favorite game: the betrayals of political rogues out to damage or embarrass enemies or a rival’s program from behind masks of anonymity. Most leaks, he said, do not come from press officers, bureaucrats or midlevel officials, who have too much to lose if they are caught.

“This leaves political appointees as the prime leakers,” Mr. Hess said. “In other words, it is the president’s own men who are most often sharing state secrets. As James Reston loved to write in his New York Times column, a government is ‘the only known vessel that leaks from the top.’” Mr. Hess offered simple advice: “Annoying as they may be, it is rarely worth the effort to plug the leaks.”

Stephen Henry Hess was born in Manhattan on April 20, 1933, to Charles and Florence (Morse) Hess. His father was an Oldsmobile dealer in the Bronx and a Republican who voted for Gov. Alf Landon of Kansas in the 1936 presidential election. His mother was a Democrat and adored President Roosevelt, who won re-election by a landslide that year.

Stephen grew up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. He attended Ethical Culture schools, which educated the children of affluent, usually liberal Democratic families in New York. He played ball in the streets and attended Saturday concerts arranged by his school. He graduated in 1951 from Ethical Culture Fieldston School in the Bronx.

After a year studying at the University of Chicago, Mr. Hess transferred to Johns Hopkins University, where he was influenced by Malcolm Moos, a political science professor and Republican Party official in Baltimore who was his mentor, tutor and friend. Mr. Hess became a Republican activist and, in 1953, received a bachelor’s degree, with Phi Beta Kappa honors, in political science.

He taught political science at Johns Hopkins, followed by service in the Army from 1956 to 1958. Mr. Moos, by then chief speechwriter for President Eisenhower, hired Mr. Hess as his No. 2. In the waning days of the Eisenhower administration, Mr. Hess assisted Mr. Moos on the president’s speech warning of the influence of the military-industrial complex.

Mr. Hess’s first marriage, to Elena Shayne, with whom he had two sons, ended in divorce in 1979. In 1982, he married Beth Amster, a teacher of French and a social worker. In addition to his son James, he is survived by his wife; by another son, Charles; two stepchildren, Peter and Sara Pozefsky; and seven grandchildren.

Mr. Hess’s most recent books include “Through Their Eyes: Foreign Correspondents in the United States” (2005); “American Political Cartoons: The Evolution of a National Identity, 1754-2010” (2011, with Sandy Northrop); and “Whatever Happened to the Washington Reporters, 1978-2012” (2012).

While studying Senate press secretaries in 1987, Mr. Hess found that their main mission was not to get the boss on network television or the front pages of national newspapers, but to get local coverage back home for the voters to see.

That often led Capitol Hill reporters to question the usefulness of the press officer — “that pre-eminent dispenser of information, withholder of detail, loyal mouthpiece and stubborn buffer for politicians,” as Mr. Hess described the job.

He liked to cite an oft-told joke.

Question: How many press secretaries does it take to change a lightbulb?

Answer: I don’t have anything on that, but I’ll get back to you.

Ash Wu contributed reporting.

Robert D. McFadden was a Times reporter for 63 years. In the last decade before his retirement in 2024 he wrote advance obituaries, which are prepared for notable people so they can be published quickly upon their deaths.

The post Stephen Hess, 92, an Eminent, and Quotable, Political Scientist, Dies appeared first on New York Times.