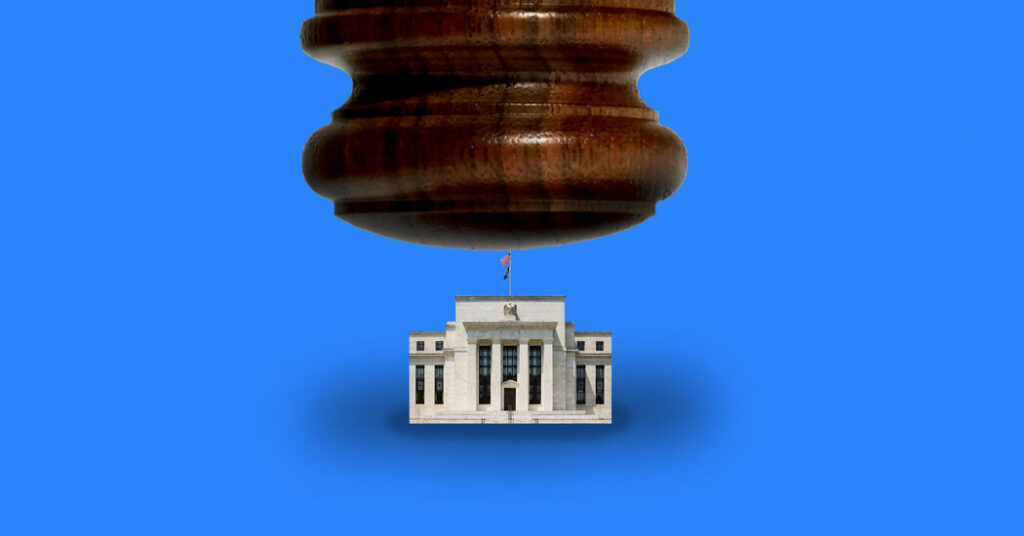

On Wednesday the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Trump v. Cook, a case focused on whether President Trump has the power to fire Lisa Cook, a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

The case is also seen as a proxy for a question with far-reaching economic and political implications: Will the Federal Reserve maintain its independence?

Legal scholars, economists, central bankers, most politicians — and perhaps even the Supreme Court itself — think the Fed should indeed maintain its independence. Though not everyone is so sure about that — or, at least, some people suggest that Fed reform is not out of the question.

In an online interview, John Guida, an editor in Times Opinion, talks with Andrea Katz, who teaches law at Washington University, about what might unfold in oral arguments — as well as how recent scholarship might apply to the case and on presidential power.

John Guida: In May 2025, in an emergency-docket ruling in Trump v. Wilcox (which temporarily allowed President Trump to remove the leaders of two independent agencies), conservative justices wrote that “the Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States” — which makes it distinct from other executive agencies.

Justice Elena Kagan, writing on behalf of the liberal justices, argued that the Fed’s independence “rests on the same constitutional and analytic foundations as that of” other independent agencies. Yet the court’s conservatives seemed intent on overturning the 1935 precedent, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, that upheld their constitutionality.

Do you think there is a majority on the court to maintain Fed independence?

Andrea Katz: The Supreme Court has telegraphed its intention in this case, which is to somehow “square the circle” of preserving the Fed’s independence while continuing to support a sweeping presidential removal power.

We’ve seen the court tip its hand recently in three places. One was the Wilcox emergency docket ruling you note above, which shows we have at least five justices willing to sign onto a Fed carveout along historical lines. The second was oral arguments in December in the Trump v. Slaughter case, where the justices focused little to not at all on historical evidence for Fed independence at the founding. (This was a shame, in my view, because as I wrote in an amicus brief in that case, the framers’ generation did have an understanding of agency independence.)

Third, and very striking for me, was Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s question to the government during the Slaughter argument. He said: “The other side says that your position would undermine the independence of the Federal Reserve and they have concerns about that, and I share those concerns. So how would you distinguish the Federal Reserve from agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission?” This question is that of someone who’s made up his mind that the F.T.C.’s independence is unconstitutional, but the Fed’s is not.

If a court majority does want to maintain Fed independence, how would it avoid treating the Fed as an exception to the constitutional validity of most independent executive agencies?

Legal scholars have proposed other theories of Fed independence. Could the court do it in such a way that would not elicit a sort of judicial eye roll of the kind that Justice Kagan expressed in her dissent?

The court can’t do it without eliciting an eye roll, certainly. The theories for why the Fed should be entitled to structural independence, but seemingly no other agency, all have big problems. (My friend and colleague Lev Menand has written convincingly on this point.)

Start with what seems to be the court’s preferred option: the “historical practice” exception (the idea that the Fed is “a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity” with roots in the founding generation). Note, importantly, that the Roberts court has already, in several areas of the law (including the president’s power to remove agency personnel), essentially said, “If we can’t find a historical ancestor for X or Y law or right, it’s unconstitutional.”

The trouble there is that nothing remotely like the Fed existed at the founding. The first two Banks of the United States (often leaned on here as support) were not actually part of the government. They were investor-owned private banks. Furthermore, they didn’t regulate banks at all: They were lenders, period. So, historically speaking, the Fed turns out to be sui generis, and a product of the early 20th century, just like its counterparts the F.T.C., the Securities and Exchange Commission and so forth.

Another argument is that the Fed actually exercises “legislative power,” because monetary policy is a power of Congress. The problem here is that, under a formalist theory of the Constitution, which the Roberts court embraces, all power has to fall under one of three headings — legislative, executive or judicial. On that reading of the Constitution, the Fed itself would be unconstitutional, as Congress would be trying to “delegate” legislative power to an agency.

A third solution is one advanced by conservative legal scholars, including Aditya Bamzai and Aaron Nielson, Will Baude and Michael McConnell. The idea is basically that “banking is different”: Monetary policy is not “executive” in nature; it’s the sort of function that “private banks can and do perform.” There’s a problem here, too: The court’s logic has been that the president has to be able to supervise officers who make policy, lest we have a sort of democratic vacuum accountable to nobody, not even the voters. If so, the fact that the Fed is “quasi-private” should make the problem worse, not better — it should be Public Enemy No. 1 because it’s making massively consequential policy decisions outside of the chain of command with the voters.

To put it squarely, the unitary executive theory should, by all rights, swallow up central bank independence, but its defenders are clearly aghast at the thought.

Given the issues you identify here, is there any chance that the court will not overturn Humphrey’s Executor, at least in its entirety, to avoid trying to contort itself?

Well, I suppose this could happen if Justice Kagan pulls off a grand diplomatic coup. Her position, which she laid out in her dissent in Wilcox, is that this is a problem of the court’s making. The court could always retain Humphrey’s and preserve independence for a select few multimember commissions (of which the Fed’s Board of Governors is one).

On the other hand, Chief Justice Roberts called Humphrey’s “a dried husk of whatever people used to think it was.” For a chief justice who’s been concerned in the past about stare decisis, this was quite striking.

So for the time being, it looks like this puzzle will remain unsolved. Let’s turn to the president’s removal power, and presidential power more broadly. In an article last fall, the conservative legal scholar Caleb Nelson wrote that the Roberts court has concentrated “ever more power in the president” — with cases this term potentially expanding it further.

Yet recent scholarship and commentary — including yours, and including that article by Mr. Nelson — have criticized or complicated (or both) the source of authority for this expansion of presidential power.

Can you explain why, and how that relates to the Fed case?

Maybe I can share a funny story. A few weeks ago, I was giving a talk pointing out the ways founding-era evidence cuts against the idea that our Constitution gives the president a removal power, and someone said loudly to me, as if I were beating a dead horse, “Yes, yes, we know, the unitary executive is dead!”

In 2020, in the landmark Seila Law case, the court laid down a kind of manifesto for the president’s removal power. The court made its case largely on historical grounds, writing that the president’s “power to remove — and thus supervise — those who wield executive power on his behalf follows from the text of Article II” and was “settled by the First Congress” in 1789.

Since Seila Law, there’s been a wave of historical scholarship challenging all the elements of this historical claim. Scholars across the political spectrum are turning against the theory.

To give an example, recent scholarship has argued that the founding generation likely didn’t have a unified view on where removal belonged under the Constitution. After all, the Constitution says nothing about removal other than impeachment, only that the president exercises “the executive power.” During the debates over our Constitution at Philadelphia, the framers said nothing about removal, either. It’s something of a stretch to say that, just 12 years after the American Revolution, the framers — silently and solely by implication — vested a power in the president that would make him practically a king.

We’re also learning more and more about early forms of agency independence seen at the founding. One independent commission created to settle the nation’s debts was devised by Alexander Hamilton, perhaps the strongest presidentialist among the framers. Clearly, he didn’t view agency independence as in conflict with the Constitution he helped to design and defend.

So there’s a strange irony right now that this originalist Supreme Court stands poised to cement the unitary executive into our Constitution at the very moment that many scholars are declaring it an ahistoric invention of the recent conservative legal movement.

In basic form, the unitary executive theory seems grounded in a sort of formulation: Vesting clause (“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America”) plus Take Care clause (“he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”) equals unitary executive.

If these are indeed the primary pillars of the theory, how does the new research contest it?

Those are the main pillars of the theory. It’s also important to note that this is an originalist theory of Article II. That means that unitary theorists believe that the Constitution’s theory of the president’s powers is fixed, and that this theory can be traced back to the ideas of the founders and the people living in their generation.

The claim is essentially that “executive power” and “take care” contain a power to fire all the officers of the government, and that, despite the Constitution’s silence on removal, early Americans understood this as a matter of common knowledge.

How would you support such a claim? One approach has been to go to the framers’ “bookshelf,” looking at intellectual influences on Madison, for example. Another has been to turn to dictionaries (the Executive Power was defined as …). Another is to say that existing models the framers would have worked with — say, the British king, or state constitutions from the 1770s and ’80s — all pointed to this shared tradition of removal power as quintessentially “executive.”

The trouble is, none of these sources provide enough evidence to surmount the key problem, which is that the Constitution says nothing about removal.

Past presidents have applied political pressure on Fed officials. But this is the first time a president has tried to remove a Fed governor. Furthermore, the Justice Department has opened a criminal investigation into the Fed chair, Jerome Powell.

Will or should the justices take into account both the Justice Department’s action and Powell’s response? Another way of asking this is, how much will or should politics weigh on legal debate?

There remains much to be written on whether, or to what extent, the court acknowledges the outside world in its opinions. In Dobbs, which overturned the right to an abortion, Justice Samuel Alito wrote: “We do not pretend to know how our political system or society will respond to today’s decision,” and even if “[we] could … we would have no authority to let that knowledge influence our decision. We can only do our job, which is to interpret the law.”

But I think that Alito’s proclamation of principled judicial indifference to the real world can’t be right, and especially not with this president. The justices’ own actions in other cases suggest that they are very much aware of the potential consequences of executive overreach. During Trump’s first term, the court struck down the administration’s attempts to smuggle a citizenship question into the census and to roll back DACA, with striking language in each case that the government’s reasoning was “contrived” or a “post hoc rationalization.”

In the recent arguments on Trump’s tariffs, too, the justices seemed strikingly aware of the danger that a president can fabricate an emergency, then claim sweeping authority to address the “crisis.” Justice Neil Gorsuch asked the government whether the president could impose a 50 percent tariff on gas-powered cars to deal with the climate crisis.

Is there anything, or anyone, you will be following closely during the Cook oral arguments? Any particular ideas, or how specific justices navigate the back and forth?

Well, first of all, I’m curious about the sorts of arguments that will be made. The oral arguments in the Slaughter v. F.T.C. case featured surprisingly little historical argument. (It seemed like Justice Sonia Sotomayor kept trying to bring history in, but to little avail.) This might be a pattern: In recent cases where the court has protected the president or his powers, it’s seemingly avoided history that wouldn’t be convenient to the argument. But I’d expect to see the historical basis for the “Fed carveout” dealt with explicitly by Paul Clement, counsel for Lisa Cook and also the former U.S. solicitor general under George W. Bush.

On the other hand, the strongest case for Fed independence is not historical, constitutional or even legal, but economic. So, will the court talk history or economics?

On that note, as for whom to watch, well, I think Justice Kavanaugh has made up his mind. He’s been defending a Fed exception for years, although when he first voiced the idea as a circuit judge, it was based on a functional-economic rationale, not a legal one.

Because the text and history don’t seem to provide a way to distinguish the Fed from other independent agencies, it will be interesting to see whether textualists like Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Justice Gorsuch are convinced by the government’s approach.

Again, I’d expect we’ll see Fed independence protected by the court, but whether on a stare decisis or historical or even prudential basis remains an open question.

Andrea Katz is a professor of constitutional law at Washington University. John Guida is a Times Opinion editor.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Has the Supreme Court Backed Itself Into a Corner? appeared first on New York Times.