In a world where President Donald Trump acts like Denmark is one of our most hated enemies and seems to view China entirely through his buddy-buddy relationship with Xi Jinping, good news in the realm of foreign policy can be hard to find.

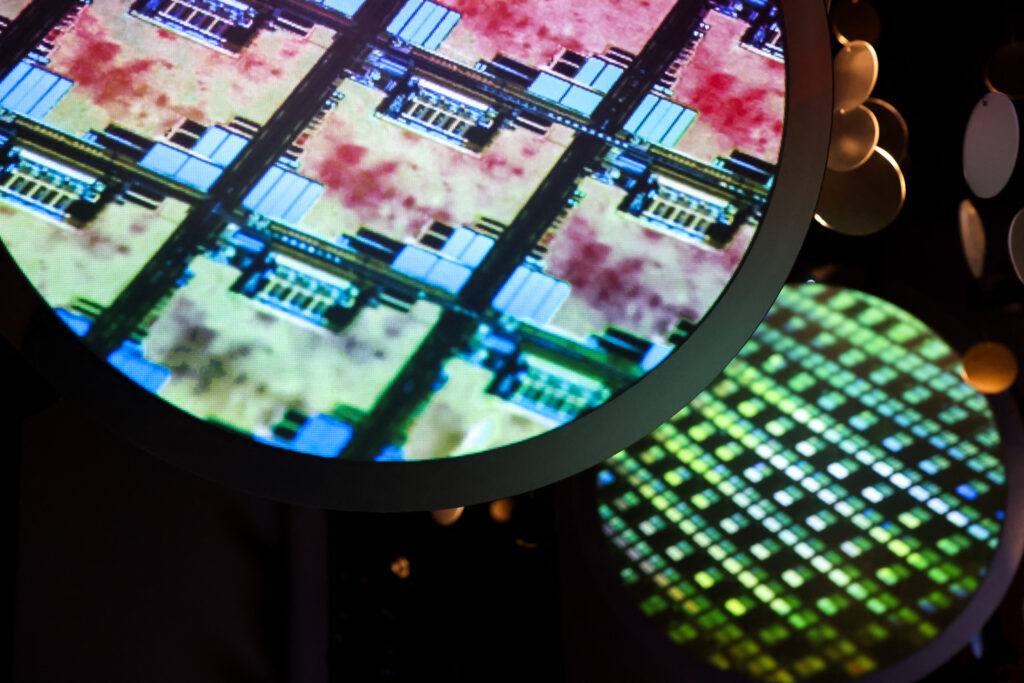

On paper, the United States and Taiwan reaching a trade deal last week is a bit of that much-needed good news. The deal cuts U.S. tariffs on Taiwanese goods from 32 percent to 15 percent, and in exchange, according to the Commerce Department statement, “Taiwanese semiconductor and technology enterprises will make new, direct investments totaling at least $250 billion to build and expand advanced semiconductor, energy, and artificial intelligence production and innovation capacity in the United States.”

The alleviation of any unneeded antagonism with a U.S. ally merits a sigh of relief, and this is great news if you want to work in a Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. factory in Arizona. The company is reportedly planning an expansion that will build several new fabrication plants in Arizona, according to the Wall Street Journal, “which would bring its total footprint there to roughly a dozen plants.”

TSMC reportedly also has plans to build four new plants in Taiwan. These may be the best of times for TSMC; Chairman C.C. Wei said last week that the company expects its chip sales to grow almost 30 percent in 2026, driven largely by booming investment in artificial intelligence. The company’s profits leaped by 35 percent in the last quarter.

Still, if you’re a Taiwanese citizen worried about the threat of an invasion by the People’s Republic of China, there’s a slightly ominous note in the news that TSMC is expanding in the U.S., as well as in Germany, Japan, and even China.

Because semiconductors power everything from phones to fighter jets, some argue that Taiwan’s central role in supplying them — especially through TSMC — serves as a deterrent to Chinese military action, since disrupting this supply would have global consequences. The nickname for the deterrent effect is the “silicon shield.” Taiwan builds its most advanced, complex chips only on the island; the moment war breaks out, the world’s access to those advanced chips would be disrupted, perhaps permanently.

In 2023, Warren Buffett sold his conglomerate’s remaining shares in TSMC, lamenting, “I don’t like its location, and I’ve reevaluated that … I feel better about the capital that we’ve got deployed in Japan than Taiwan. I wish it weren’t so, but I think that’s the reality, and I’ve reevaluated that in the light of certain things.”

Later that year, when I visited Taiwan, Connie Chang, director general of overall planning for Taiwan’s National Development Council, told me, “Honestly speaking, if something happened to Taiwan, probably half of the world’s industries will shut down.” Even if that’s an overestimation motivated by self-preservation, a shooting war in the Pacific or a blockade of Taiwan would be a calamity for the global economy.

Under the “One China” policy, the U.S. government recognized the regime in Beijing as the sole legal government of China, acknowledging the Chinese position that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of it. In practice, the U.S. often keeps an aircraft carrier group in the region and repeatedly emphasizes, “The United States supports peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait and opposes unilateral changes to the status quo, including by force or coercion.” That sounds neutral, but no one worries about a Taiwanese invasion of mainland China.

Is America’s goal to protect the advanced TSMC manufacturing plants from the threat of Chinese invasion? Or is it to protect the 23 million people living in a U.S.-allied, modern, thriving, multiparty democracy with the rule of law and freedom of expression?

Three years ago, Vivek Ramaswamy, running for the Republican presidential nomination, offered a stark assessment of what the U.S. priority ought to be: “My message to China is clear. Do not mess with Taiwan before 2028. And before 2028, our commitments are strong. After 2028, we have semiconductor independence. We have very different commitments, lower commitments, significantly lower commitments to a situation in which you’re sorting out a nationalistic dispute dating back to 1949.”

Unspoken but clear in that assessment is the notion that starting in 2029, a U.S. that has “semiconductor independence” doesn’t really care if China invades Taiwan or not.

Today, Ramaswamy is running to be governor of Ohio — with Trump’s endorsement.

U.S. policy ought to be that America wants to deter a Chinese invasion because free nations have the backs of other free nations. Instead, a protectionist, mercantilist president is in charge, one who sees foreign policy in purely transactional terms, has not an iota of appreciation for long-standing U.S. alliances, and will nab a Venezuelan dictator in the middle of the night, only to leave his morally indistinguishable right-hand woman in charge.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick says 40 percent of Taiwan’s supply chain could be reshored to the U.S. before Trump’s term ends in 2029. Taiwanese officials contend that’s unrealistic, but either way, this administration’s aim is to reduce U.S. dependence on Taiwan’s chips as much as possible, as quickly as possible. Once the U.S. can make enough of its own advanced chips, how motivated would Trump or any future president be to deter a Chinese invasion?

That “silicon shield” isn’t looking so sturdy.

The post Would Trump abandon Taiwan? This deal is slightly alarming. appeared first on Washington Post.