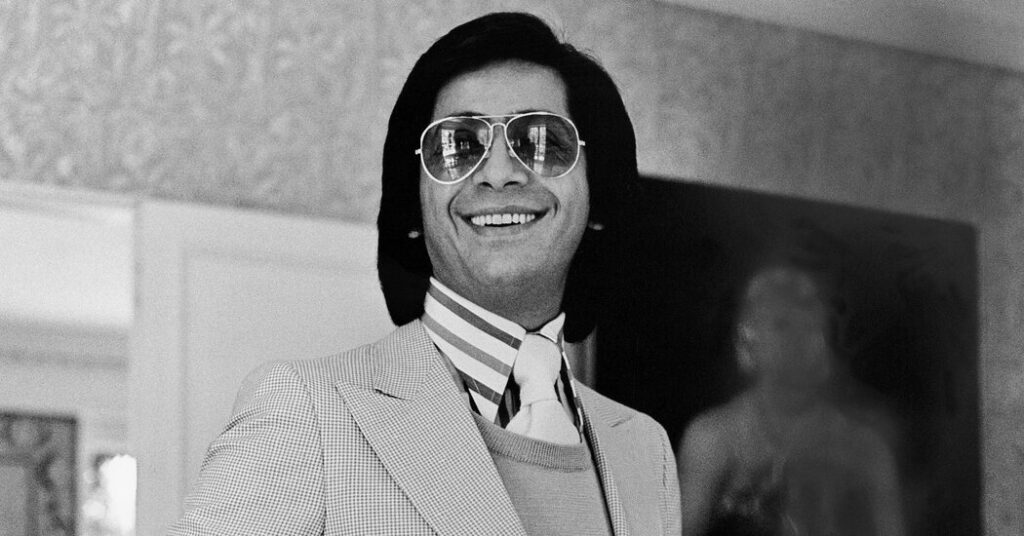

Many words have been used to describe the work of Valentino Garavani, the Italian fashion designer who died on Monday at 93 — usually “elegant,” “beautiful,” “feminine” and “glamorous.” “Rich” has come up less often, perhaps because it is more complicated.

But “rich” was also one of the hallmarks of Valentino’s style. And it is possible that because of who he dressed, how he dressed them and how he lived, the designer did more to shape the perception of how it looked to be rich, at least in the latter half of the 20th century, than any social registrar or paparazzo hanging out by the Hotel du Cap.

Valentino’s clothes were not easy. They were not relaxed. They had structure and manners and the grace and hauteur of noblesse oblige. They demanded a certain carriage — and their own carriages. They were always appropriate and rose to the occasion. As a designer, he believed in the power of the carefully placed ruffle and the perfect bow. He had a horror of the miniskirt, and grunge gave him the willies.

His signature color was ruby; his suits were made for the charity luncheon, his sweaters for Gstaad and his gowns for the opening night at La Scala. They offered the protection of taffeta and chiffon — of taste, that elusive weapon — against the eyes of the ogling world. In Valentino’s hands that wasn’t frivolity. It was strategy.

But while his work was meant for those to the manor (or chateau or palazzo) born, Valentino, a man who built his own empire on his vision and the strategy of his partner, Giancarlo Giammetti, defined that right not by bloodline but by personal brand.

Little wonder royalty of all kinds and those who aspired to its trappings gravitated to his designs, especially when they had to step out in public. There was even a name for his acolytes: Val’s gals.

Jacqueline Kennedy wore Valentino for her marriage to Aristotle Onassis and when she attended her first Met Gala, in 1979. Queen Maxima of the Netherlands wore Valentino for her marriage to Crown Prince Willem-Alexander, and duty-free princess Marie-Chantal Miller wore Valentino to wed Crown Prince Pavlos.

Princess Rosario of Bulgaria was officially a muse; so were Gwyneth Paltrow and Anne Hathaway. Imelda Marcos was a client. Ditto Farah Pahlavi of Iran and Susan Gutfreund of the go-go 1980s.

They trusted Valentino to understood their needs because he didn’t just design their outfits; he designed a realm of his own, one that defined his brand as much as any “V” logo. One that involved, ultimately, five houses and a yacht. Chief among them was Château de Wideville, the 17th-century residence outside Paris that once housed Louis XIV’s mistress, Louise de La Vallière, and had 12 gardens, including a lilac pool, and men whose job was raking the white pebbles on the paths.

Valentino always wore a suit and tie and traveled with an entourage and a separate car to carry his suitcases. He had faith in the symbolism of a deep tan and the importance of a morning grooming routine — for himself and his five pugs — and the well-orchestrated dinner party. He collected china for 40 years and once told me, “A beautiful, interesting table is an expression of a joy and respect for your guests, or just yourself.” He could wax lyrical about antique salt cellars and elaborate napkins.

Even after he sold his brand and retired in 1982, he would follow the social season (at least the old jet-set social season) around the world, bestriding red carpets from New York to London and Paris to the Alps. His life was his style, and his style mirrored his life.

Now, of course, such a depiction of wealth and such a schedule seem like a quaint anachronism.

Billionaires wear hoodies and sneakers, not taffeta and bugle beads. They buy land in New Zealand and build rocket ships. Designers themselves are employees for hire, rather than kings of their domain. They take their runway bows in T-shirts and jeans, and brands belong to conglomerates. “Lifestyle” has become a marketing ploy. The house of Valentino has itself evolved under its current designer, Alessandro Michele, to be more eccentric, rich-person cosplay than society armor.

That is why so many of the memorials flooding social media since Valentino’s death have declared “the end of an era.” That phrase is not just a reference to fashion, though it is true that after the deaths of Karl Lagerfeld in 2019 and Giorgio Armani last year, the generation of designers who built so much of the postwar wardrobe (or at least the Western idea of the postwar wardrobe) is being lost.

It’s a reference to the world, and promise, that such fashion once represented.

Vanessa Friedman has been the fashion director and chief fashion critic for The Times since 2014.

The post The Way ‘Rich’ Once Looked appeared first on New York Times.