Bernie Goetz is still here.

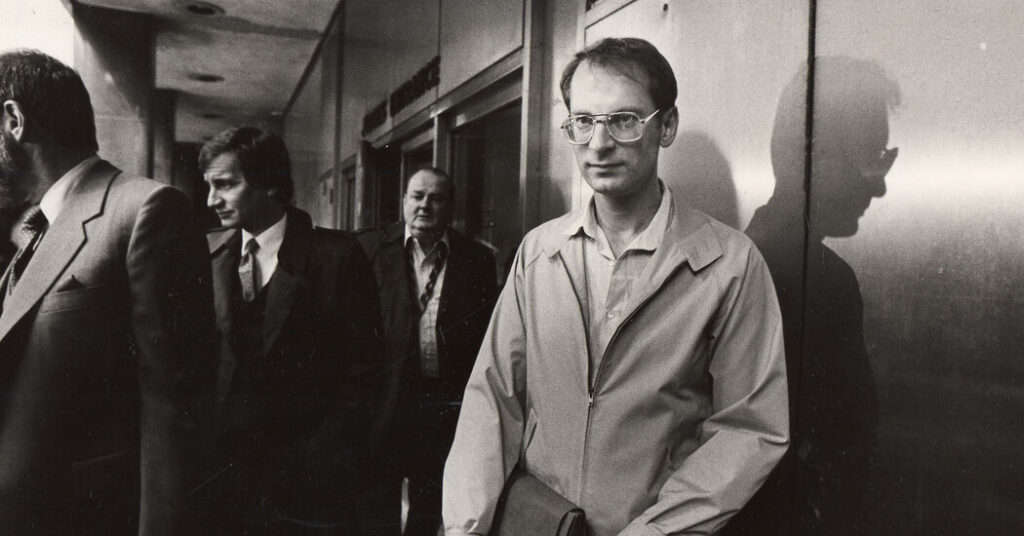

The white man who shot four Black teenagers on a downtown subway in December of 1984 is right where we left him, in the same Manhattan apartment where he lived the day he boarded a No. 2 train carrying an unlicensed handgun. All four survived, although one was paralyzed and brain-damaged. Goetz’s subsequent trial, on charges including attempted second-degree murder, convulsed New York City.

For years, details of the case were endlessly debated. Was this self-defense or reckless aggression? In the city’s graffiti-covered and crime-ravaged mid-80s, Goetz was both admired as a righteous vigilante and reviled as a trigger-happy racist.

Now 78, Goetz still runs an electronics repair business out of his home. He also rehabilitates injured squirrels, a passion that has caused more than a little friction with his landlord and neighbors. While the man has remained rooted in place, his story has mostly faded from memory.

That is about to change.

In the span of a week, two books about the Goetz case will be published, both of which link the case to contemporary debates about race, guns, vigilantism and media bias. Oddly enough, both books will be published by imprints at Penguin Random House — and both were originally slated to be released on the same day in February, until, a few weeks ago, both moved up their publication dates.

If this was about jockeying for a head start, then Elliot Williams, a former prosecutor and CNN legal analyst, has grabbed an early lead.

His book, “Five Bullets: The Story of Bernie Goetz, New York’s Explosive ’80s, and the Subway Vigilante Trial That Divided the Nation,” publishes on Jan. 20. A week later comes “Fear and Fury: The Reagan Eighties, the Bernie Goetz Shootings, and the Rebirth of White Rage,” by the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Heather Ann Thompson.

Both books dive into the grisly particulars of the shooting and the six-month trial that ended with Goetz acquitted of the most serious charges. (He was convicted of criminal possession of a gun and served eight months in prison.) In a 1996 civil trial brought by Darrell Cabey, the teen he’d paralyzed, Goetz was found liable and ordered to pay $43 million in damages. He filed for bankruptcy and has never paid a dollar.

Both authors strive to draw nuanced portraits of the shooting victims, who struggled with both physical and psychic wounds. (Two of them, Barry Allen and James Ramseur, have died, the latter possibly by suicide.) Both authors delve into Goetz’s life, too, and he emerges as a flinty eccentric, a man incensed by nearly everything about New York City. Even the accents of the police who interviewed him during his two-hour confession, nine days after the shooting, made him writhe in his seat.

He has changed little in the intervening decades, though his opinion of his hometown has softened. Occasionally, he sounds pleased enough to pass for a booster.

“NYC is nothing like it was 40 years ago,” he wrote in a recent email. “Good shopping and you don’t have to own a car.”

‘Here’s another’

People under 40 may not know his name, but for a while, Bernhard Goetz was pop culture’s most improbable phenomenon. He made the cover of Time magazine and was name-checked in songs by Lou Reed, Billy Joel and the Beastie Boys (“Pick pocket gangsters paying their debts/Caught a bullet in the lung from Bernie Goetz”).

He’s been an answer in Trivial Pursuit and a question on “Jeopardy!,” and he’s mentioned in a 1991 episode of “Seinfeld.” According to Williams, he likely inspired the subway shooting scene in the 2019 film “Joker.”

Goetz’s path to notoriety began with a spasm of violence that lasted less than 20 seconds, and both books unspool it in harrowing slow motion. Cabey, Allen, Ramseur and their friend Troy Canty were traveling from the Bronx to a video arcade in Lower Manhattan. Canty either asked for or demanded $5 from Goetz. Feeling threatened and cornered, Goetz, who was 37 at the time, shot and wounded all four of the teens.

Goetz initially thought he’d missed Cabey. “You don’t look so bad. Here’s another,” he remembered saying. Then, Goetz told authorities, he fired his last bullet.

He fled the scene and drove to New Hampshire in a rented car. As police looked for the shooter, he became a folk hero to many New Yorkers traumatized by more than 1,300 murders a year. (By comparison there were 305 in 2025.)

He eventually turned himself in at a police station in Concord and offered a lengthy confession filled with rage and sarcasm, viewable on YouTube. It shows a tense, wiry man in oversized glasses and a button-down shirt, lecturing detectives as though they were the city he blamed for forcing his hand. His only regret, he says, was running out of ammunition.

While his chances at trial seemed slim, his lawyer, Barry Slotnick, argued that much of Goetz’s confession was the fantasy of a “traumatized, sick, psychologically upset individual,” including the “here’s another” line. He contended that Goetz took “proper and appropriate action” against thugs, as he called the teens, who had surrounded and menaced him.

Both books devote several chapters to the trial, which is filled with so much tension and dramatics that it feels like the contrivance of a screenwriting hack. At one point, Slotnick arranged to have four members of the Guardian Angels re-enact the subway confrontation in the courtroom, recruiting the largest Black men in the organization as stand-ins. There was a morning field trip to an identical subway car at a nearby station. Both helped convince the jury that Goetz was in genuine danger.

“We were very uncomfortable with what he did,” Mark Lesly, who served on the jury, said in a recent phone interview. “But that didn’t mean that we were going to find him guilty.”

More than a few Black leaders denounced the verdict at the time, and still describe it as a disgrace.

“I felt it was a blatant miscarriage of justice,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton. “I did not ever say that the young men were choir boys. But do you have the right to execute people based on who they are? That was the fundamental question, as far as I was concerned, and it put all of us in danger.”

Erasing the victims

Elliot Williams was 8 years old when the Goetz shooting occurred. He was born in Brooklyn to Jamaican immigrant parents, and his first memory of the case springs from a segment on the evening news in early 1985, about a “subway vigilante” turning up in the lyrics of hip-hop songs. He’s been thinking about the legal and cultural legacy of the case, as well as its fraught racial dynamics, since he attended law school.

The idea of a book project began a few years ago. After an internet deep dive, he realized that the careers of more than a few modern machers of the five boroughs were launched, or boosted, by the Goetz case.

“What struck me at the time is all the ancillary origin stories that start with Bernie Goetz,” Williams said in an interview. “Rupert Murdoch was a big one, Al Sharpton, Rudy Giuliani. All these guys benefited in some way from this story being in the news.”

“Five Bullets” ends with an account of a phone interview with Goetz, snippets of which are posted to Williams’s Instagram feed. Goetz monologues irritably for 45 minutes about the case, as well as about race, politics and weed, which he believes should be legalized long ago. He testily deflects a question about whether he still owns an unlicensed handgun, and retreats not one inch on his actions on the subway 41 years earlier.

“One of the things that comes through, and came through in my interview with him, was how unrepentant he was and is about the shooting,” Williams said. “To some extent, he believes he committed a public service.”

Thompson, a professor of history at the University of Michigan, grew up in Detroit. She won the Pulitzer in 2017 for “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy,” a work that took 13 years. She was gearing up to write about the Philadelphia Police Department’s 1985 bombing of a rowhouse occupied by members of MOVE, a Black liberation group, which left 11 dead.

“Then the world changed,” she explained by email. “The Trump campaign happened, his first term unfolded, his loss to Biden and the Jan. 6 nightmare. All these events persuaded me that I should pivot.”

Thompson chose not to try to contact Goetz. Instead, she took an archival researcher’s approach to convey the obstacles facing young Black men in the South Bronx of the mid-80s. This includes relations with the police, who told the press that several of the young men were carrying sharpened screwdrivers, a notion repeated by the tabloids as well as by The New York Times. It made the teens sound like predators.

Actually, the screwdrivers were unaltered and were being carried to steal quarters at a video game arcade, the teens later said. The tools were also concealed, as the trial made clear, which means Goetz could not have regarded them as a threat.

“To me it is just stunning the extent to which the victims of brutal shootings, that left one paralyzed for the rest of his life, were not treated as victims at the time,” Thompson said, “and also that they have been largely erased from this critically important historical event since.”

In both books, the teenagers are heard from largely through relatives, in interviews conducted decades ago. Cabey’s mother, Shirley, is quoted in Williams’ book from a 1985 story in The New York Times. “I told him, ‘You have two strikes against you,’” she says. “‘You’re black and you’re poor, so you better get back to studying.’”

Williams was surprised to learn, a year into his research, that his Goetz book had company. But he added that the story is “incredibly ripe,” with plenty of angles. Thompson said she is “super excited to see how these books riff off each other.”

Executives at Penguin Random House did not mention any face palm moment when they realized they had acquired two books about the same niche topic, originally to be published on Feb. 10. Different imprints at the house, they noted, don’t coordinate with one another. (“Five Bullets” is from Penguin Press, “Fear and Fury” from Pantheon.)

“You always feel for the authors, above all, when you discover that two writers have spent a great deal of time and effort going down the same long road,” said Casey Denis, a senior editor at Penguin Press who edited “Five Bullets.” “I’ve no doubt the books differ in fascinating and important ways, owing to the individual perspectives they’ve brought to this subject.”

Life after ‘the incident’

Bernie Goetz did not retreat into obscurity. He ran for mayor as a minor party candidate in 2001, pushing vegetarian menus for schools and jails, then for public advocate in 2005, with a platform that stood against circumcision and in favor of power naps for city workers. He was arrested in 2013 after selling $30 of pot to a female undercover officer.

In recent years, he’s had a couple of lunches with Lesly, the former juror, who sensed that Goetz wanted to hash over details of the case and relive the moment when he was one of the most famous men in the country.

“I got there right on time at our first lunch and he’d already finished his food,” Lesly recalled. “He didn’t seem to think there was anything strange about that.”

Reached last month by phone, Goetz at first declined to comment for this story.

“There are certain parts of society that I don’t want to be associated with anymore,” he said, “and The New York Times is one of them.” Then he hung up.

He was more expansive on email, where he projects the exasperation of a man who is pretty sure he’ll be misunderstood and doesn’t have the time to explain himself. He hopped from topic to topic — movies, politics, animal rescue — and sent a photograph of himself releasing a woodchuck into a forest in Pennsylvania.

Like nearly everyone in this drama, he has not changed his opinion about “the incident,” as he calls the shooting.

“The important thing is I shot the right guys,” he said, “and no innocent bystanders were hurt.”

His case was scrutinized in a six-part 2023 podcast and turned up recently in “The Gods of New York,” Jonathan Mahler’s book about the city’s mid-80s travails.

And now come two entire books. Is Goetz indifferent? Filled with dread? Something in between?

He answered with a comment about the questioner.

“You are a nut living in a bubble,” he wrote. Elaborating further, he sounded unconcerned: “Books are only a source. The internet is the public record.” He plans to wait a few months and buy each book for less than $10 on eBay.

Both “Five Bullets” and “Fear and Fury” end with ruminations on what would happen if Goetz committed the same act today. Williams believes that lower crime rates and progress in race relations offers some hope that the victims of an identical shooting would now be regarded as fully formed humans, not caricatures.

Even so, a modern Goetz would likely find plenty of support with a huge swath of the public. “America still loves vigilantes,” he said.

Thompson has a darker take. To her, the 2024 acquittal of Daniel Penny, a white former Marine who fatally choked Jordan Neely, a mentally ill Black man, on the New York City subway, suggests not much has changed.

“That case, and the very conservative direction of the courts, which have produced a spate of ‘stand-your-ground’ laws, all make the kind of vindication Goetz experienced in 1987 far more likely,” Thompson said. “He was the beginning of it.”

David Segal is a business reporter for The Times, based in New York.

The post The Subway Vigilante Who Never Left Is Back appeared first on New York Times.