Brian Albrecht is chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics and co-writes the newsletter Economic Forces.

On the 2023 campaign trail, Vice President Kamala Harris’s first major economic speech included proposing a ban on so-called “price gouging.” Jason Furman, a top economist in the Obama administration, said it was “not sensible policy.” As economists across the political spectrum will tell you, capping prices would discourage new companies from ramping up supply, invariably creating shortages. Donald Trump called the plan “SOVIET Style price controls.” He was right, if overly dramatic.

Harris’s proposal ended with her campaign. President Trump’s flirtation with controlling markets is just getting started.

We’ve just seen two examples. On Jan. 9, Trump announced he wants credit card interest rates capped at 10 percent for one year. But price controls aren’t the only way to command markets. On Jan. 13, Trump endorsed the Credit Card Competition Act, which would force large banks to route transactions through at least one network other than Visa and Mastercard. The bill doesn’t cap prices directly. It tells banks how to conduct their business because politicians have decided they know better.

The love affair with price controls is not partisan. Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont) and Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) have already introduced legislation to cap credit card interest rates. New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani (D) won his race promising to freeze rents for 2 million residents. When socialists and populist Republicans converge on a policy, it’s usually a sign that politics has overwhelmed economics.

The political appeal to “do something” is obvious. Americans owe roughly $1.23 trillion in credit card debt, with average interest rates approaching 23 percent. Trump can cast himself as defending working families against Wall Street. Voters love a villain.

The economic logic is just as obvious, even if price-control advocates ignore it. Credit card interest rates aren’t arbitrary. They reflect the risk of lendingto borrowers with different credit profiles. Higher-risk borrowers default more often, so banks charge higher rates to offset those losses. A 10 percent cap makes lending to millions of these borrowers unprofitable. Banks won’t offer products at a loss. These borrowers won’t get lower rates. They won’t get credit cards at all.

Trump’s markets-by-edict approach isn’t brand new. Eight months ago, the president signed his “most-favored-nation” executive order on prescription drugs, commanding pharmaceutical manufacturers to match the lowest prices they charge anywhere in the world or face regulatory retaliation. He has threatened manufacturers with “every tool in our arsenal” if they don’t meet his price targets.

We have good evidence of what happens when politicians command medical prices down. Last year, economists Yunan Ji and Parker Rogers studied what had happened since 2009, when Medicare imposed aggressive price cuts on medical equipment including oxygen machines and insulin pumps. New product launches fell by 25 percent. Patent filings dropped by 75 percent. Lower prices,but also fewer new devices.

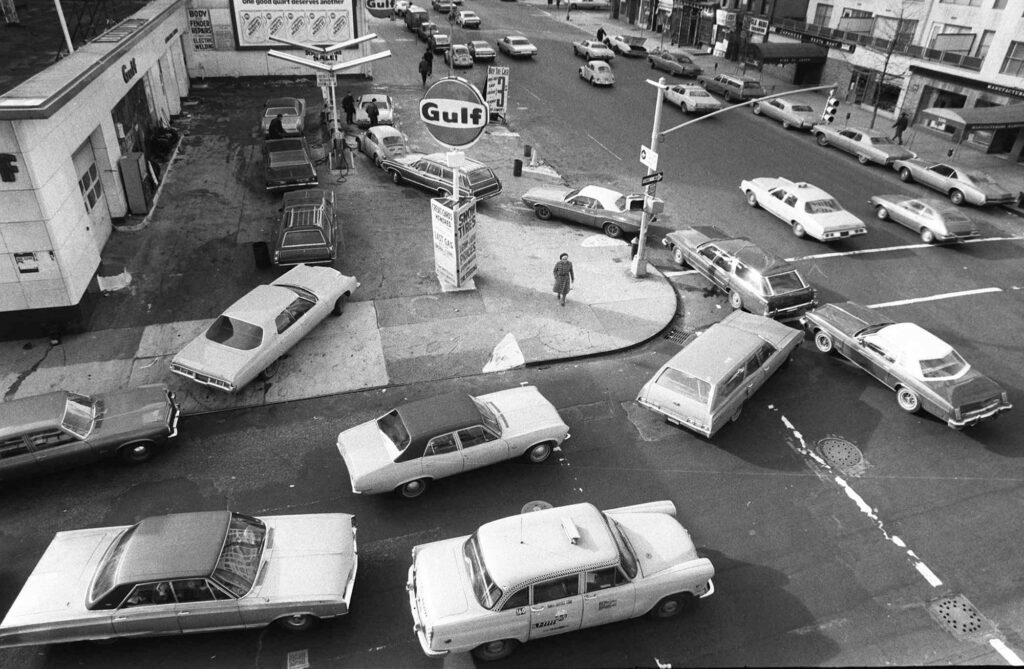

That’s the norm with price controls. President Richard M. Nixon’s gasoline price controls in the 1970s produced hours-long lines at gas stations and “Sorry, No Gas Today” signs. Some may have forgotten the scale: According to AAA data at the time, 20 percent of stations in New York and New Jersey were completely out of gas when surveyed. In Maryland, that figure reached 30 percent. Price could no longer ration scarce fuel, so time and availability did instead—sometimes violently, as some drivers would arrive at the station armed.

Or consider rent control. When San Francisco expanded it, landlords responded by converting their rental units into condominiums, which most renters could not afford to buy. A study by economists Rebecca Diamond, Tim McQuade and Franklin Qian found that rent control reduced the city’s rental housing supply by 15 percent and ultimately pushed rents higher citywide, the opposite of its stated goal.

With credit cards, as with medical devices or even rental units, those costs won’t be immediately visible. Borrowers shut out of mainstream credit don’t suddenly have cash on hand; they turn to payday lenders, pawnshops and other high-cost alternatives that often charge even higher effective interest rates, with fewer consumer protections. Banks, meanwhile, will cut rewards programs, tighten credit standards and raise other fees to compensate.

Trump demanded banks voluntarily comply with his cap by Jan. 20, the anniversary of his inauguration. This reveals a fundamental confusion about how markets work. He wants banks to provide expensive services at below-cost prices, funded by what exactly? Good intentions? Presidential pressure? The economics don’t change because a politician wishes them to.

The bills always come due. Credit card users will lose access to credit. Riskier borrowers will be driven into worse alternatives. Drug development will slow. Voters will relearn why economists, almost without exception, oppose price controls.

Prices are a signal about scarcity. You can’t eliminate scarcity by shooting the messenger.

The post Trump was right about price controls, until he embraced them appeared first on Washington Post.