Despite the carnage in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan, and even in the face of the Trump administration’s apparent determination to dismantle what remains of the liberal international order, the human rights attorney Philippe Sands insists he is not giving in to despair. “It’s too early to write off the rules-based system, too early to write off the United States,” he says. “It’s a long game.” Coming from Sands, who has devoted most of his career to trying to contain the darkest human impulses, the cautious pessimism is almost encouraging. He concedes, however, that it does feel as if the lessons of the 20th century are being cast aside and that the same sinister spirits that led to Auschwitz, Rwanda and Srebrenica are enjoying a revival. “There is definitely something in the air.”

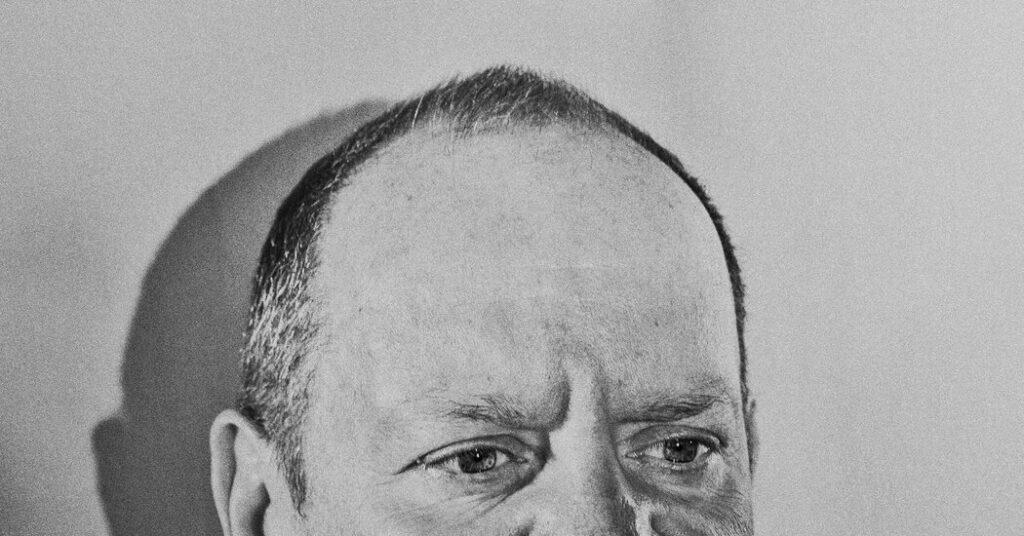

Sands, who is 65, is among the pre-eminent figures in his field and has taken part in a number of landmark cases. He was a lawyer for Croatia in the genocide claim that it brought against Serbia, helped lay the groundwork for the prosecution of the former Liberian president Charles Taylor and was a member of the legal team that sought to hold the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet accountable for torturing and murdering political opponents. More recently, he was the lead outside counsel in the successful campaign to get Britain to return the Chagos Islands to Mauritius and argued for Palestinian self-determination in a case before the International Court of Justice. He also played a key role in the establishment of a tribunal to investigate Russia for crimes of aggression against Ukraine. Over the last three decades, few people have done more to shape the direction of international criminal law than Sands.

But the London-based barrister’s reach extends beyond legal circles; he is also an acclaimed nonfiction author. His best-known work, “East West Street,” published in 2016, is a deeply affecting account of his family’s experience during the Holocaust and the parallel tale of two of the founding fathers of international human rights law: Raphael Lemkin, the lawyer who coined the word “genocide,” and Hersch Lauterpacht, the lawyer who conceptualized the notion of crimes against humanity. The book, which has been translated into 30 languages, showed Sands to be a gifted historian and an even better storyteller, with a knack for suspenseful pacing (which he credits to the influence of John le Carré, who was a friend and neighbor).

His latest book, “38 Londres Street,” was recently released in the United States. It recounts the indictment of Pinochet in 1998, his arrest in London and the ultimately unsuccessful quest to make him stand trial. The book, which takes its name from the building in Santiago that housed one of Pinochet’s clandestine torture centers, is also about the relationship between Pinochet and Walter Rauff, a senior SS officer — he developed the mobile gas chambers that the Nazis used to murder around 100,000 people — who fled to Chilean Patagonia after World War II.

The book is well timed. Scenes in the United States of masked law enforcement officers grabbing people off the street have evoked comparisons to Pinochet’s Chile and to Argentina’s Dirty War. Sands, whose wife, Natalia Schiffrin, is American (his brother-in-law is the Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz), says there is “at least the embryo of a parallel.” What especially troubles him is the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision granting presidents almost blanket immunity. As Sands asks: “If a president commits crimes against humanity, tortures or disappears people, is he going to be subject to examination by the courts? The answer appears to be no.” Sands fears that the Supreme Court, 80 years after the Nuremberg trials established that political and military leaders could be held accountable for atrocities against their own citizens, has ushered in what he calls a “new age of impunity.”

On the international front, certainly, the Trump administration feels unconstrained by existing laws and norms, a point demonstrated by the U.S. military incursion into Venezuela and acknowledged with disarming candor by the president himself in a subsequent interview with The Times. “I don’t need international law,” Trump said. Amid all this upheaval, Sands is currently arguing another major case before the I.C.J.: He is representing Gambia in the genocide claim that it filed against Myanmar over its treatment of the Rohingya people. The trial opened last week in The Hague and is scheduled to run through the end of the month. If Sands and his colleagues prevail, it will mark the first time that a state has been held responsible for genocide. The I.C.J. has no direct means of enforcing its judgments, however, and in the context of the current moment, the courtroom proceedings might seem like a forlorn attempt to add scaffolding to a collapsing edifice.

Last January, Sands delivered a Holocaust Remembrance Day lecture at the University of Cambridge, his alma mater. Although his work often immerses him in stories of appalling cruelty, he is by nature very cheerful, and he exuded warmth and affability as he reflected on his Cambridge education and talked about his career. He counseled the students against cynicism. He noted that international human rights law was still in its nascency and said he remained optimistic that its core values would ultimately triumph. “I firmly believe that the arc of history will follow the arc of justice,” he said.

But he acknowledged that history seemed to be taking an unfortunate detour. Donald Trump was back in the White House, and Elon Musk had given what many observers interpreted to be a Nazi salute at an inauguration event and had also told a far-right rally in Germany that it was time to move beyond the country’s past, and Sands conceded that it was hard not to feel a sense of foreboding. “This could end very badly,” he said.

He grew up in the shadow of bleak times. His mother, Ruth, is a Holocaust survivor; as a toddler, she was spirited out of Vienna by a Christian missionary named Elsie Tilney and spent several years in France in the care of a series of Catholic families who hid her Jewish identity. Sands was raised in London (he holds British and French citizenship). His father, Allan, was a dentist; Ruth owned a children’s secondhand bookstore. He has a younger brother, Marc, who recently retired as an executive at an art auction house.

Sands entered Cambridge in 1979 intent on studying economics. But he quickly soured on supply-and-demand curves and switched to law. He found that pretty stultifying too, except for the class he took on international law. Although the professor was, in Sands’s words, “a very dry Yorkshireman,” he was enthralled by the subject matter. He says that it was “about all these things that were not talked about at home but were very, very present.”

Upon graduating, he spent a year as a visiting scholar at Harvard Law School. In 1984, he returned to Cambridge to work as a fellow at the university’s Research Center for International Law, which was under the direction of Elihu Lauterpacht, Hersch Lauterpacht’s son, with whom he formed a close bond. At the time, international law was an extremely circumscribed niche, mainly involving border disputes and other technical matters. After the breakthroughs at Nuremberg, international criminal law had become largely moribund owing to the exigencies of the Cold War.

By contrast, international environmental law was an emerging subfield full of promise, and Sands became one of its pioneering figures. His foray into environmental law began with a paper that he wrote on transboundary pollution after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986. He helped start the Alliance of Small Island States, which has been at the forefront of the battle against climate change, seeking to ensure that the interests of island nations, which are particularly threatened, are represented in negotiations over emissions reductions and other measures. In 1995, he helped write what remains a widely used textbook on international environmental law. Sands is now active in the movement to have ecocide — loosely defined as illegal or wanton acts committed in the knowledge that they are very likely to cause severe environmental damage — recognized as an international crime.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War created an opening to finally build on the legacy of Nuremberg, and the Balkan wars and the Rwandan genocide gave added impetus to that work. Pinochet’s arrest in 1998 in London appeared to mark a turning point in the fight for accountability: He was the first former head of state ever detained on foreign soil under the principle of “universal jurisdiction” — the idea that some crimes are so egregious that every nation has a right and a duty to seek to punish those responsible for them.

The British government released Pinochet in 2000, however, citing health concerns, and Sands says that after Sept. 11, the effort to make international criminal law more comprehensive and binding became significantly harder. According to Sands, “38 Londres Street” is in part an “elegy” for the time in the 1990s when the global human rights system seemed to take another step forward.

Still, even as progress slowed, Sands gained recognition for his deep knowledge of the law and for his litigating skills, and his expertise was sought not only by victims of human rights abuses but also by a few notorious oppressors. After Saddam Hussein was deposed and captured in 2003 by U.S.-led coalition forces, intermediaries reached out to see if Sands might be willing to provide legal advice to the Iraqi dictator if he was brought before an international tribunal (Sands wasn’t, and Hussein was convicted and sentenced to death by a special tribunal of Iraqi judges).

A few years later, at the request of the Syrian government, Sands traveled to Damascus to discuss with President Bashar al-Assad the legal jeopardy that he might face as a result of the 2005 assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri of Lebanon. There was speculation that the Syrian government played a part in his killing, and al-Assad wished to know if he, as a head of state, could claim immunity from potential prosecution. Sands told him he could not. He says that he was offering “an independent opinion” to al-Assad and was never asked to represent him. He adds that upholding international law occasionally requires speaking to the bad guys too.

Sands, who is on the faculty of University College London and is also a visiting professor at Harvard Law School, came to prominence in the United States mainly because of a personal investigation that he undertook into the use of torture in the war on terrorism. He interviewed a number of officials from the Bush administration, and in 2008 he published a book called “Torture Team” in which he accused six of them, all lawyers (including the former U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez), of sanctioning war crimes.

To Sands, the treatment of prisoners at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib was a shocking betrayal of the values that the United States claimed to represent, and President Obama’s failure to hold those officials accountable remains a source of disappointment to him. Even so, he continued to regard the United States as generally a force for good in the world. The postwar global order was principally an American creation, and this extended to the advancement of human rights. “The United States was the architect, very largely, of the rules that I have been involved with my whole life,” Sands says. “We saw it as the mansion on the hill, the guardian of the idea of the international rule of law.” But a year into Trump’s second presidency, that no longer seems to be the case. “We are beginning to have to imagine doing the work we do without having the United States as a backstop,” he says.

In 2010, Sands was invited to give a lecture at the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv. He had never been to Lviv, a city in western Ukraine, close to the Polish border, but it was where his maternal grandfather, Leon Buchholz, was born and raised. Buchholz, who eventually settled in Paris, rarely spoke of Lviv or of the family that he lost in the Holocaust, a conspicuous silence during Sands’s childhood. After accepting the invitation, Sands decided to research the family history that Buchholz had never shared. In short order, he discovered the tragic fate of Buchholz’s mother and dozens of other relatives, and he learned too that Raphael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht had both attended law school in Lviv. Sands also became acquainted with the sons of two of the men responsible for the deaths of his family members: Niklas Frank, whose father, Hans, administered German-occupied Poland during World War II and who was among the Nazi officials convicted at Nuremberg and executed; and Horst von Wächter, whose father, Otto, was the Nazi official in charge of Galicia, which included Lviv.

Sands told the stories of Hans Frank and Otto von Wächter and of how their sons reckoned with their crimes in a compelling 2015 documentary, “My Nazi Legacy,” which he wrote and narrated. Niklas Frank, who became a journalist, renounced his father and wrote a book harshly condemning him. Horst von Wächter is a more complicated figure. Although he later opened his family’s archives to Sands, he could not bring himself to accept his father’s culpability. The film’s most poignant scene comes when Sands, Frank and von Wächter visit the field not far from Lviv where in 1943 around 3,500 Jews were executed and buried, including some of Sands’s relatives (as well as relatives of Hersh Lauterpacht). Troops under the command of von Wächter’s father took part in the massacre. As Frank and von Wächter stand before a memorial commemorating the atrocity, Frank says, “This our fathers did.” From von Wächter’s stricken look, it seems clear that he knows the truth, but even then, he refuses to admit it.

A year after the documentary was released, Sands published “East West Street.” Part of the book is about the Nuremberg trials and the behind-the-scenes jockeying between Lemkin and Lauterpacht over how the defendants were to be charged. Lemkin wanted them tried for what he called “genocide” — for murdering people because they were members of a particular group, for killing Jews because they were Jews. Lauterpacht didn’t dispute that Jews had been victimized because of their identity, but he pushed to have the defendants charged instead with what he called crimes against humanity — with killing people as individuals. He believed it was essential to try to steer humanity away from tribalism and hoped that international law could serve that purpose. As Sands writes in “East West Street”: “By focusing on the individual, not the group, Lauterpacht wanted to diminish the force of intergroup conflict. It was a rational, enlightened view, and also an idealistic one.”

Lauterpacht prevailed at Nuremberg: In October 1946, 18 Nazi leaders were convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity, but the judgments against them made no mention of genocide. Lemkin’s lobbying efforts did not go unrewarded, however. Two months after the verdicts in Nuremberg, the United Nations voted to designate genocide an international crime. And in the decades since, largely owing to the enduring resonance of the Holocaust, genocide has come to be regarded as the more consequential and damning accusation — the “crime of crimes,” as Sands puts it. He finds this regrettable; crimes against humanity are no less heinous than acts of genocide, and he believes they should carry just as much opprobrium. But the bigger problem, in his mind, is that because the word “genocide” has such powerful connotations, it is often used carelessly and as a cudgel.

The pitfalls of the genocide charge became apparent to Sands when he represented Croatia in the case that it brought against Serbia in 1999 (another lawyer on the team was Keir Starmer, now Britain’s prime minister). The allegation centered on the massacre in November 1991 of several hundred Croatian P.O.W.s and civilians by Serbian paramilitaries; the killings took place near Vukovar, a city in Croatia. When the I.C.J. finally issued a decision, in 2015 (the wheels of international justice are especially slow to turn), it declined to categorize the slaughter as genocide. The ruling infuriated Croats, and their outrage was compounded by the fact that the same court had earlier affirmed that the 1995 massacre of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica, also by Serbian paramilitaries, did meet the definition. (The court ruled that those Serbian units committed genocide but concluded that the Serbian government itself could not be held responsible for the atrocities.)

Sands told me that this remains a source of resentment in Croatia. “Many people believe there will be another war because the Croats didn’t get their genocide. And their anger is against the Bosnians, who got a genocide. So you ask yourself the question: Why is that a socially useful outcome?” He says that Lauterpacht anticipated the danger in elevating genocide to a crime — that it would sharpen tribal instincts and make it more likely, not less, that eliminationist desires would be acted on — and that he has come to share this view. Intellectually, he stands with Lauterpacht.

At the same time, he admits that he is very sympathetic to Lemkin’s position. During a talk at the City University of New York last March, Sands recalled visiting the site near Lviv where his relatives were murdered. “Standing above that unmarked mass grave,” he told the audience, “it was impossible for me as someone who is Jewish not to feel a sense of kinship and connection with the people who were there simply because they were Jews who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.” They were unquestionably the victims of a genocide. So were the Tutsis in Rwanda and the Bosnian Muslims who were massacred in Srebrenica. And despite his frustration with how promiscuously the genocide charge is invoked, Sands is confident that he can make it stick in the case against Myanmar.

In late 2016, the Myanmar government launched a bloody crackdown on the country’s Muslim Rohingya population. It is believed that thousands of people were killed, and hundreds of thousands fled abroad. United Nations investigators found evidence of widespread human rights violations, including summary executions, infanticide, gang rape and the pillaging and burning of entire villages. In 2019, Gambia filed a genocide claim against Myanmar. The American law firm Foley Hoag, which represents Gambia, enlisted Sands as an outside counsel. Arsalan Suleman, a partner with Foley Hoag, told me that Sands was a natural choice. “He’s a great attorney to have on your side,” Suleman says.

More than six years later, Gambia v. Myanmar has now gone to trial at the I.C.J. Under international law, genocide is difficult to prove. Sands and his colleagues must be able to show dolus specialis, or specific intent: They have to establish, through direct evidence or compelling circumstantial evidence, that the only reasonable inference the judges can draw is that the atrocities committed against the Rohingya were motivated wholly or partly by genocidal impulses. On the first day of the hearings, Sands told the court that his side would demonstrate that the violence inflicted on multiple villages by Myanmar’s military met that threshold. Just as in Srebrenica, he said, what occurred in those villages presents “the inescapable conclusion that the crimes against the Rohingya who lived there were perpetrated with genocidal intent.”

One reason the trial in The Hague is being closely watched is the implications that it might have for a case that the I.C.J. is expected to hear later this year: the genocide allegation that South Africa has brought against Israel over the war in Gaza. A determination that Myanmar committed genocide could foretell a similar judgment against Israel. If, on the other hand, the I.C.J. clears Myanmar, it would be interpreted as a positive sign for Israel. Many observers think the court would be reluctant to turn history on its head by making Israel the first nation found guilty of genocide.

What’s more, the judges will be under considerable pressure, because the case against Israel could have onerous consequences for them. The Trump administration has sanctioned a handful of judges and one prosecutor with the International Criminal Court over its 2024 decision to issue arrest warrants for Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and its former defense minister Yoav Gallant for war crimes and crimes against humanity, and it will undoubtedly seek to punish the I.C.J. if it rules against Israel. (The I.C.C. prosecutes individuals; the I.C.J. adjudicates disputes between countries.)

For now, Sands is not involved in South Africa v. Israel. He has been cautious in his commentary about the conflict in Gaza. He believes that the charges against Netanyahu and Gallant are justified but has demurred on the genocide question. This has drawn criticism. Nimer Sultany, a Palestinian human rights attorney who teaches at SOAS University of London, says that by late 2024, there was consensus among scholars that Israel could credibly be accused of genocide, and he suggests that Sands had a moral obligation to speak out. “Sounding the alarm on genocide to pierce through obfuscation and propaganda is one way to try to stop atrocities under the cover of war and self-defense,” Sultany says.

According to Sands, there is a simple explanation for his reticence: He hasn’t wanted to make any public statements that might prejudice the Myanmar case. What he is willing to say is that he thinks Lemkin would have regarded Israel’s military campaign in Gaza as genocidal, but so too the Oct. 7 Hamas terrorist attack that prompted it. He also points out something else. In 2019, Time magazine published an article about Netanyahu that noted that he was reading “East West Street” and included a photo of him with the book in his hand. Sands’s son (he has three children) had the picture framed. “One thing we can say with certainty,” Sands says, “is that Benjamin Netanyahu is well aware of what Raphael Lemkin considered the crime of genocide and needs no lessons from anyone on the dangers he is likely to face on the basis of his actions.”

But even as he argues another case in The Hague, Sands has come to believe that the law isn’t the only avenue for establishing truth and accountability, or necessarily always the best one. Near the end of his talk in Cambridge, Sands took questions. One student suggested that as a condition for ending the war in Ukraine, Russia was likely to demand that any criminal charges against Vladimir Putin and other officials be dropped. (The recent peace plan endorsed by President Trump included full amnesty for all parties.) How, he asked, would Sands “balance the tension between stopping more violence and seeing justice for violence that has already happened?”

Sands said that in any situation in which a civilian population has been brutalized, the crimes must be acknowledged. “You have to find a way to address what happened,” he said. But he went on to tell the student that his work as a writer had broadened his view of how justice might be achieved. He mentioned, by way of example, the role that literature has played in helping Chile recover from the horrors of the Pinochet era. “It has had a profoundly important impact,” Sands said. He also cited Patrick Radden Keefe’s book “Say Nothing,” about sectarian violence in Northern Ireland.

Being a lawyer had taught Sands the limits of the law; being an author had given him even greater appreciation for the power of the written word, and he now thought that books could sometimes be a more effective instrument in the pursuit of redress. “If I had to choose between a single judgment in an international court on some horror that has happened or a very fine work of literature addressing that issue, I would probably choose the work of literature,” he said, “because it is more likely to bring peace and reconciliation.”

Michael Steinberger is a contributing writer for the magazine and the author of “The Philosopher in the Valley: Alex Karp, Palantir, and the Rise of the Surveillance State.”

The post No Country Has Ever Been Held Responsible for Genocide. Can This Lawyer Change That? appeared first on New York Times.