How does the Cleveland Orchestra stay the Cleveland Orchestra?

The winters pass, the summers bloom, and still this ensemble maintains its reputation as one of the finest in America. It may not enjoy the largest budget around, but for listeners who are unbothered by its habitual emotional reserve, its sophistication and rigor make it all but an ideal orchestra.

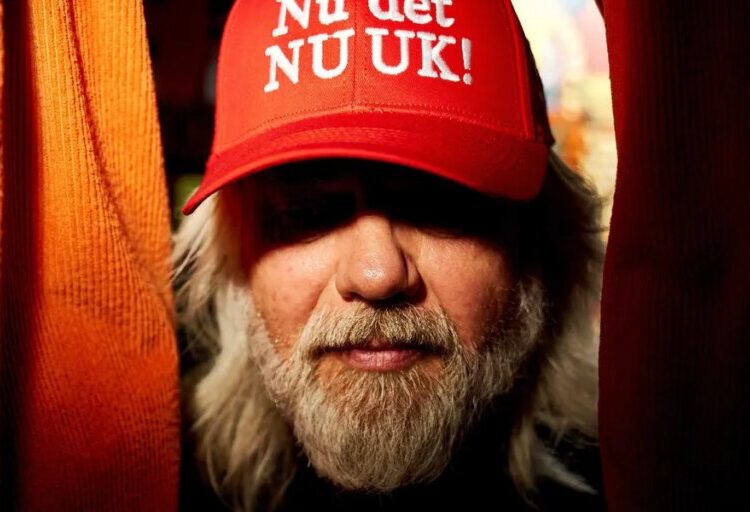

Searching for an answer, I spent three days in Cleveland to see how the orchestra prepares a program from first rehearsal to first performance under its music director, Franz Welser-Möst. The program was a study in contrasts: Mozart’s “Jupiter” Symphony and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 11, which cleverly celebrates the Russian revolution of 1905 while condemning the Soviet Union’s suppression of the Hungarian revolution of 1956. You can hear it at Carnegie Hall on Wednesday, the night after the orchestra performs Verdi’s Requiem there.

It says a lot that this orchestra is confident enough to let a critic see it rehearse from start to finish, on the record. Perhaps it says more that I was not allowed to sit onstage, to guard against distractions.

From a box near the stage, though, it was abundantly clear that although Welser-Möst, who has been music director for more than 23 years, is demanding, his relationship with these players is intuitive enough that much can be taken on trust and experience. Care was pronounced. There was a sense of pride.

But there were also some rules. Rehearsals in Cleveland, as elsewhere, are governed by labor agreements. Schedules vary, but most programs receive four rehearsals of up to two and a half hours: one on Tuesday morning, two on Wednesday and a dress on Thursday morning, before the concert that night. A clock looms onstage. Efficiency is imperative.

BY MY WATCH, the orchestra tuned at precisely 9:59 a.m. on Tuesday. Welser-Möst had been standing silently on the podium for a while. He said good morning, wished the players a happy new year and raised his baton. For the next 20 minutes, as the group played through the first movement of the Shostakovich, he said nothing. He leaned back against the railing, gently beating time to force the musicians to listen to each other, as if they are the chamber ensemble he has always said they should be.

Even the Cleveland Orchestra gets rusty after the holidays, but Welser-Möst let them play, and soon it was audibly itself. “With all due respect, I doubt if any other orchestra comes as well prepared as this one,” the conductor said in one of four interviews before each session. “You start on a different level.”

Preparation means different things to different musicians. Michael Sachs has been principal trumpet since 1988, and consults scores marked with notes from any number of conductors. Eliesha Nelson has been a violist for a quarter century; she practices “the technical stuff that I know I need to brush up on,” she said, “but the musicality really comes together best when we’re all rehearsing.” Nathaniel Silberschlag, the principal horn, is 27 and still faces works he has never played before. “A lot of the time for me,” he said, “that means listening with the score and finding where my part relates to others.”

Sachs remembers joining the orchestra and being told by players who were hired by George Szell, the music director from 1946 to 1970, that their first rehearsals were like performances elsewhere. Szell said something similar, but Welser-Möst guesses that the expectation dates back further. “It’s in the DNA of this orchestra,” he said.

“Of course, when the boss is here, sure, there’s maybe an extra effort,” he added, laughing. “They like to be prepared.”

TWO THINGS ARE STRIKING about Welser-Möst at work. One is forensic precision, whether in his instant recall of the bar numbers of things that need to be fixed or his painstakingly erasing tiny intonation discrepancies. “Certain things, it’s like brushing your teeth,” he said. “There’s certain routines you have to have to keep the orchestra really clean.”

If Welser-Möst talks to the players, he is exact. Explaining why chords had to start and end completely together in the first movement of the Shostakovich, which depicts a January morning in St. Petersburg, he said, “it’s ice, not melting ice.” The same music also needs to feel like as if a revolution is imminent. “Think fortissimo, but don’t play that way,” he told the timpanist Zubin Hathi, who was playing quiet, ominous motifs.

The second thing of note was how Welser-Möst managed the psychology of leadership. He spoke firmly and showed controlled frustration, but muffled his authority when he could. If he stopped the music, he said sorry. He addressed musicians by their instrument, taking the personal out of the professional. Criticism began with “Maybe it’s my fault, but.” Praise was given when it was earned.

The musicians concentrate hard and enforce their own standards; miscreants who are caught on their phones are punished by having them buy doughnuts for everyone else. But they appreciate the balance Welser-Möst strikes. “He is absolutely in charge,” Sachs said, “but the thing that’s great is, it really comes from his basic knowledge. It’s very clear that he’s saying things with purpose and meaning and function.”

For Welser-Möst, this is about respect. Coming into a rehearsal and blithely imposing his own concept on a piece would be offensive to successful musicians. “I think you can only demand respect if you show respect, and I demand respect for the position” of music director, he said. “You have to be aware that power is only lent to you. Don’t abuse it.”

THE SHOSTAKOVICH REHEARSALS were diligent but reasonably simple. Welser-Möst spent most of his time making it sound “unmusical,” as he put it, flattening phrases that the players naturally shaped to more accurately depict the rigidity of tsarism and communism. The performance I heard was similar to the dress rehearsal, so intense that it made my jaw hurt.

But in the Mozart, Welser-Möst’s demeanor changed entirely as he tried to teach the orchestra to play a symphony like an opera. He stopped to give briefings on Enlightenment-era music theory and recent research. Trying to get the first movement to sound festive, he wryly suggested they all listen to the finale of “Le Nozze di Figaro,” knowing that some musicians would do it at home. He spoke like a scholar but also flopped around to exaggerate how loose things sounded.

“You can’t tell them, ‘Oh, play it like opera,’” he said. “You have to act out a little.”

For an hour on Wednesday morning, things turned more intense. There were bad habits to dust away, Welser-Möst said, and aesthetic confusions to clarify. But the Clevelanders soon got the gist. Come afternoon, Welser-Möst sent them home an hour early. “The orchestra knows exactly what I want,” he said, “on which track the whole thing is going to drive.”

He had toiled, for example, to get the third movement trio to sound like a ländler, an Austrian folk dance. “I could have done it seven more times,” he said, “but they have to digest overnight what I want.” After a few more tries in the dress rehearsal the next day, they nailed it, to palpable relief. “Exactly!” Welser-Möst exclaimed. “Ja!”

Unlike the Shostakovich, the Mozart was transformed in concert. Excellent in the dress, it became an exhilarating display of communication in performance. Welser-Möst had kept the music fresh, and now, gesturing busily to bring sections into a collective song, he reaped the reward.

Practice can only do so much. “Even if you had 35 rehearsals, there’s still this element of surprise,” Welser-Möst said, “because there are hundreds and hundreds of people in the same room which haven’t been there before.”

That’s one reason the work is never done. “Perfection does not exist,” he said, “and still we drive toward perfection.”

The post How the Cleveland Orchestra Stays at the Top of Classical Music appeared first on New York Times.