CRUX, by Gabriel Tallent

After the phenomenon of the Neapolitan quartet, a mudslide of knockoff narratives — novels and films laying bare the nuances of platonic friendship — was inevitable. That nothing has lasted quite like Lenù and Lila’s story speaks to the vastness of Elena Ferrante’s achievement and, perhaps, to the difficulty of crafting a story not powered by the reliable tensions of carnal desire and family discord.

In his assured second novel, “Crux,” Gabriel Tallent asserts that friendships are as intricate and significant as any relationship bound by blood or romance.

If “Crux” were an episode of “Friends,” it would be called “The One Where They Go Climbing.” “They” are Tamma Callahan and Dan Redburn, two high school seniors and BFFs whose friendship is the core of the book. Tamma is poor, queer and given to breathless rants that are by turns profane and poignant. Dan is straight, steady and poised to be the first in his family to attend college.

Both are die-hard climbers, much to their families’ chagrin. The sport is potentially deadly, not least when you’re in the Mojave Desert and your shoes are potholed and your rope (read: your actual lifeline) came from a dumpster, clearly discarded because it’s “suuuuuuper coreshot” (read: can’t save you). “LIKE: OH EM GEE! BUY ANOTHER ROPE!” one of Tamma’s climbing idols says at a competition. “Literally you could die — lit-er-al-ly DIE!”

But like most adrenaline junkies, Tamma and Dan are infatuated with climbing because of its dangers. They also hope that the sport will allow them to transcend their circumstances; they’re literally and metaphorically trying to climb out of the holes that are their lives.

Tallent is especially deft with the lingo of climbing. “Above her and to the right, lay the flake, an overlap of granite, its wavering left-facing edge worn white from the traffic of other climbers,” he writes. “With each move, she swam her arm up and sank her jam.”

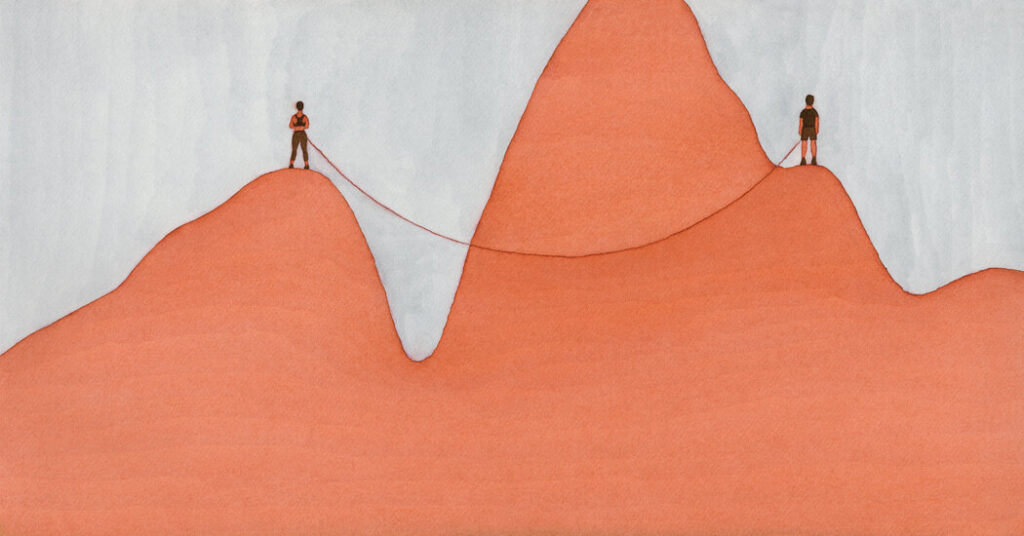

For most readers, the prose will amount to an immersive language course where fluency is achieved through brute experience. The effect is as exhilarating as “sending” (successfully climbing) an arduous “problem” (route up/across a boulder or mountain). The parlance of climbing extends beyond the action of the sport; Tallent deploys it to initiate readers into the subculture of climbing, the teenagers’ consciousnesses and, forgive me, their tender hearts. “The foundation of route climbing is the rope team — two people holding each other’s lives in their hands.”

But the language of climbing is also where the book misses some footholds. Because the vernacular is already so loaded with metaphor, the prose is at times overwrought. “It’s cruxes that matter,” Tamma tells Dan. “The top is only a symbol, and without the crux, it refers to nothing. The crux is the heart of the boulder.” At his best, Tallent uses the language of the sport to deepen the book’s mysteries, but when he uses it to moralize or solve his character’s dilemmas, it can feel as though he distrusts his readers or like he’s targeting a young adult demographic.

Fortunately, the novel always regains its balance. Tallent is skilled in animating the whiplash of teenage emotion. Tamma fixates on her climbing heroes, various fleeting girl-crushes and the demands of her splintered family. Dan, meanwhile, careens between the specter of college scholarships, Tamma’s adventurousness in contrast with his own timidity, and his mother.

Another of the novel’s pleasures is how Tallent handles the rising stakes of the story. When a tragedy befalls her older sister, Tamma is saddled with responsibilities far beyond her capacity. In another writer’s hands, this would be the predictable rite of passage where the character nobly sacrifices innocence for wisdom. But Tallent swerves: Rather than blossom, Tamma spirals. “Every minute of every day, I’m terrified, just terrified,” she says, “except when I’m out climbing, which is weird if you think about it, because that’s the only time I could actually die, except no, that’s when I’m calm, and everything else is scarier, because it’s worse than death.” Likewise, when Dan’s mother’s health craters, he doesn’t grow up so much as grow numb.

Ultimately, the dismal circumstances cleave the kids not just from each other and climbing, but also from themselves. Tallent might telegraph the novel’s ending, but the way he executes the conclusion is thrilling, propulsive and earned.

Risk is part of climbing’s allure, but the real draw of the sport, what keeps people coming back, is akin to why we read novels: We want to extend beyond ourselves and view the world from new vantage points. Sure, the terrifying possibility of crashing to the ground is always there, but so is the profound comfort in knowing someone — a reliable writer or trusted friend — will be waiting, as Tamma tells Dan, “to make of that wasteland a church and a home.”

CRUX | By Gabriel Tallent | Riverhead | 408 pp. | $30

The post A Rowdy, Electric Novel About Rock Climbing — and Friendship appeared first on New York Times.