This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Today, Donald Trump announced that he is considering using the Insurrection Act to send the U.S. military to Minneapolis if state officials do not quell anti-ICE protests there. Deploying federal troops on American soil against the objections of state and local officials is an extreme measure––and seems likelier to inflame than to extinguish unrest there, given that needlessly provocative actions by ICE officers helped create conditions on the ground. Yet the president seems eager to suppress the actions of people he calls “professional agitators and insurrectionists.” For months, members of his administration have laid the rhetorical groundwork for a martial crackdown.

Insurrections are rare in U.S. history, but according to White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, we’ve had lots of them just since 2024. In his telling, the perpetrators of recent insurrections against the United States include Joe Biden; the Colorado Supreme Court; U.S. District Judge Indira Talwani; U.S. District Judge Jennifer Thurston; Democrats; protesters in Los Angeles; protesters in Paramount, California; protesters in Compton, California; the city of Los Angeles; U.S. District Judge Maame Ewusi-Mensah Frimpong; various “radical communist judges”; the Chicago Police Department; a crowd that the Chicago police didn’t stop; an Oregon judge; and “Democrat lawmakers.” (Miller has never called the MAGA movement’s storming of the Capitol an insurrection.)

The rhetorical abuse of insurrection is part of a larger pattern. The president and his allies constantly engage in what we might call threat inflation, giving Americans the impression that they face catastrophe on all sides and that the government therefore must respond maximally. In the administration’s telling, drugs enter America via not smugglers, but “narco-terrorists.” Immigrants never sneak into America; they “invade.” And anti-ICE protesters are “domestic terrorists” and “insurrectionists.” These designations rarely match the reality on the ground. Instead, they stoke fear beyond what reality justifies.

A particularly extreme example occurred just last month: Trump issued an executive order that declared fentanyl “a weapon of mass destruction,” a dubious turn in the history of that term. The phrase weapons of mass destruction was coined by Archbishop Cosmo Gordon Lang after the 1937 bombing of Guernica to anticipate the massively damaging aerial bombings of future conflicts. “Who can think without horror of what another widespread war would mean,” he wrote, “waged as it would be with all the new weapons of mass destruction?”

The term grew only more apt with the advent of the atom bomb, and has been used in recent decades to refer to existential threats to cities or even nations. It had not typically been used to refer to any of the voluntarily ingested substances that kill lots of Americans, such as alcohol, cigarettes, and cocaine—until the Trump administration sought to justify the extrajudicial killing of drug smugglers and perhaps to prepare the public to accept military escalation against various drug cartels.

Nor does the logic of the new use stand up to scrutiny. If the CIA discovered a plot to smuggle a weapon of mass destruction, as that term is understood by most Americans, into the Port of Long Beach, no president would hesitate to shut down the whole West Coast supply chain and search every container until the nerve agent, biological weapon, dirty bomb, or nuclear device was found. Yet if a kilogram of fentanyl, theoretically enough for 500,000 overdoses, were in a container ship, the U.S. government would not shut down a major port to find it. Tens of thousands of pounds of fentanyl are smuggled into the U.S. every year.

Clear thinking requires us to distinguish between the existential emergency posed by weapons of mass murder and substances that cause many deaths accumulated slowly over time, as more and more people use them. And the Trump administration would most likely reject applying its own logic consistently. For example, if a news organization waited for fentanyl shipments to arrive in a bunch of U.S. cities and then led a prime-time broadcast with the storyline Trump and his national-security team failed to stop WMD attacks on at least 20 American cities last month, the White House would rightly argue that the outlet was misleading and manipulating its viewers.

The American public is similarly misled each time Trump or members of his team erroneously assert that the country confronts a superlative threat. Terrorism is another word the administration likes to throw around—a particularly ironic threat to exaggerate, in that the intention is to stoke more public fear to achieve political goals. After the ICE officer Jonathan Ross shot and killed Renee Good in Minneapolis, Americans spent days watching and arguing about videos of the incident. Reasonable people disagreed about how to apportion blame. Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem could have waited for an investigation before commenting; if she chose to speak, she could simply have argued that the woman who was killed gave the officer in front of her car reason to fear for his life. Instead, she not only presumed to know the motive of the woman who was killed; she also attributed to her the most malign motive possible. “What happened in Minneapolis was an act of domestic terrorism,” Noem declared. Vice President Vance has bizarrely called the incident “classic terrorism.”

The absurdity of Vance’s designation is most evident if, as David French suggested in the The New York Times recently, you compare videos from Minneapolis with actual terrorist attacks. “Many of us have seen footage, for example, of the horrific ramming attack in Nice, France, in 2016 that killed 86 people—or of the domestic terror attack in Charlottesville, Va., the following year, where a white supremacist drove directly into a crowd of ‘Unite the Right’ counterprotesters, killing a woman, Heather D. Heyer, and injuring dozens of others,” French wrote. “In both cases, the murderous intentions of the men driving the vehicles—deploying them as weapons—were unmistakable.”

Trump does not lack the capacity for understatement. In February 2020, at the beginning of a pandemic that would kill more than 1 million Americans, he said, “One day—it’s like a miracle—it will disappear. And from our shores, we—you know, it could get worse before it gets better. It could maybe go away. We’ll see what happens. Nobody really knows.” That’s how Trump talks when he wants the country to keep its cool.

Confronted with far less deadly threats in his second term, Trump and his allies inflate them daily. They do so to push policies that overreact to the country’s challenges rather than carefully calibrated responses. In the process, their rhetoric fuels the polarization that makes political violence and civic instability more likely. There is less to fear from reality than from the administration’s fearmongering itself.

Related:

- Donald Trump wants you to forget this happened.

- Jonathan Chait: Trump has odd views on domestic terrorism.

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- Rubio won; liberty lost.

- Democratic bosses are launching a remake of the 2028 calendar.

- Franklin Foer: MAGA’s Jewish intellectuals helped create their own predicament.

Today’s News

- The Venezuelan opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner María Corina Machado visited the White House to urge President Trump to back democratic elections in Venezuela.

- Trump threatened to invoke the Insurrection Act to deploy U.S. troops to Minneapolis if Minnesota officials fail to quell protests that erupted following two shootings, one fatal, by two federal officers.

- Trump said yesterday that he would hold off on attacking Iran for now, after being told by “very important sources on the other side” that the government had stopped killing protesters. He said that he would continue to monitor the situation and warned that he would be “very upset” if the crackdown resumed.

Dispatches

- Time-Travel Thursdays: Published 250 years ago, Common Sense is perhaps the most consequential piece of political writing in American history—and maybe its ideas are what we need now, Jake Lundberg writes.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

Will Google Ever Have to Pay for Its Sins?

By Gilad Edelman

If the story of journalism’s 21st-century decline were purely a tale of technological disruption—of print dinosaurs failing to adapt to the internet—that would be painful enough for those of us who believe in the importance of a robust free press. The truth hurts even more. Big Tech platforms didn’t just out-compete media organizations for the bulk of the advertising-revenue pie. They also cheated them out of much of what was left over, and got away with it.

More From The Atlantic

- Jonathan Chait: Elizabeth Warren’s abundant mistakes

- The U.S. military can’t do everything at once.

- Radio Atlantic: Do ICE officers have “immunity”?

- An apocalypse film that will prompt wild cheering

Culture Break

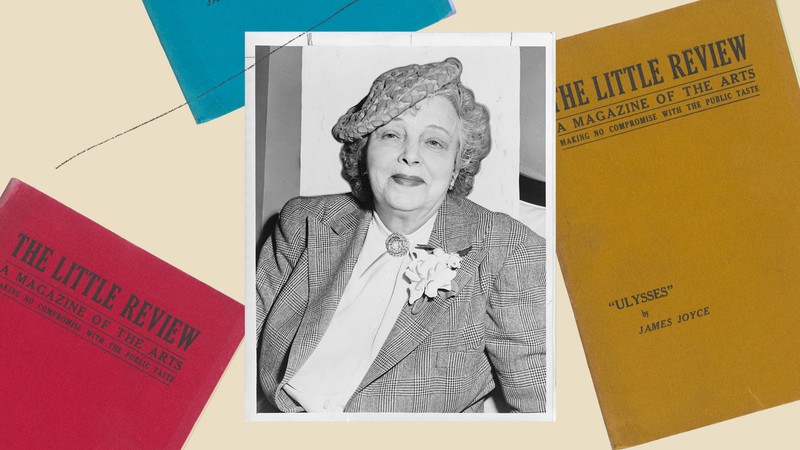

Read. Margaret C. Anderson was at the center of a notorious literary-obscenity trial, Sophia Stewart writes. Then she was forgotten.

Explore. Last month, The Atlantic’s Science desk compiled 55 facts that blew our staffers’ minds in 2025.

Rafaela Jinich contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post The President Who Cries Emergency appeared first on The Atlantic.